Abstract

Ballet has been used through the centuries as an agent for spoken and unspoken sociability on the stage, in the audience and behind the scenes. Britain had an aversion to the French form of ballet and associated its presentation and culture as indulgent excess. The 1730s-1820s ballet relied on British affluent, well-heeled theatregoers to uncouth, standing-room only on-lookers, as a conduit for support and sociable endorsement without which the art form of ballet would not survive. The functionality and intersectionality of ballet performance and the nature of social relationships are complex. Being a flashpoint, women and their bodies were the central connection of social interactions.

Keywords

Arising out of the French court, the ballet during the long eighteenth century in England evolved into a performing arts staple and an event for lively interaction. The French form of ballet, initially transferred to Britain during the 1700s, underwent a transmutation to suit British sensibilities of restraint and understatement. Performances in theatres during what was known as seasons, became an anchor for civic functions for wealthy attendees, whose theatre presence was part of their societal duty. As this arena opened to soldiers and the working class, it became a currency for increasing one’s status in one’s own social circle. Some patrons of dance considered ballet performances of secondary importance. Paramount for required performative sociability was the interaction of the audience members and constant maintenance of social standing amongst themselves. Ballet performance attendance was deployed to introduce potential business partners, create business agreements, marriage matchmaking and exert social dominance to elevate one’s social standing. These acts brought more recognition and possible resources to the family. Conversations about the ballet itself and the dancers were wound around and threaded through behaviors of sociability, creating a commonality and an entrée for more interactions.

Ballet’s Growth in England

During the nineteenth century, the English ballet reached its apogee between 1830 and 1840. This popularity was slowly seeded and grown with the arrival of French dancers whose training and performance careers arose from the Paris Opera, established by Louis XIV in 1669 as the Académie d'Opéra.1 British audiences showed distaste for the French ballet’s decadence and required their own version of the art form. The English choreographer and dancing master, John Weaver, was a catalyst for this acceptance and progression, timed with London’s blossoming as a metropolis. Weaver was an exceptional dancing master from London well-known on the public stage. He offered dance instruction, created ballets, and published dance treatises cleverly making dance a necessary commodity to ensure the maintenance of one’s social standing and scalability.2 A genius, Weaver formed the idea of ‘distinctly English and very polite’ art form of ballet and moved it towards pantomime and the ancient Greeks.3 Yet still an appetite for French dance existed.

England provided a generous escape for choreographers and dancers from the tumultuous after-effects of the French Revolution. Prior to the Revolution, Marie Sallé, famously recognized as the first female ballet choreographer and a somewhat controversial dancer, visited London as a child with her brother. The child prodigy performed English choreographer Kellom Tomlinson’s ballet called The Submission at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.4 While in England, Sallé saw John Weaver’s ballet, The Love of Mars and Venus (1717). Certainly, the climate and love hate appetite for French dance lured Mademoiselle Sallé to return to London. In her ballet, Pygmalion (1734) she reduced the embellishments of French ballet norms, simplified her costumes to a Greek tunic and danced without a wig, her unbound hair freely flowing with her movements. The work of Weaver influenced her artistry as a choreographer, a rarity among female dancers of the time.5 Another progressive dance revisionist, Jean-Georges Noverre, brought his Ballet D’Action to Drury Lane Theatre.6 This created an anticipatory frenzy amongst the elite for more ‘exotic forms of entertainment’ that was embedded with subject matter opportunities for conversation, evaluation, and judgement. A propitious, entrepreneurial visit and performance in 1815 by the famed Auguste Vestris, named ‘le Dieu de la Danse’ further enflamed monied society’s appetite for ballet. His son, the popular dancer Armand Vestris was married to Londoner opera singer Elizabetta Lucia Bartolozzi. Even Princess Charlotte Augusta (1796-1817) was not immune to the popularity of the ballet. Her steady patronage at Covent Garden until her early death in 1817 provided more motivation to go to a performance as her presence in the royal box offered a perfect stage for the Princess’s behavior; and romantic relationships were one of gossip and discussion. Newspaper narratives about performances could include tidbits about whom was in attendance of the performance; their behavior, dress, and companions were a source of prestige and ruination.

- 1. The Académie d’Opéra went through several iterations of names. Shortly after its founding, it was renamed the Académie Royale de Musique when Jean-Baptist Lully became its Director. Today it is known as the Paris Opera Ballet.

- 2. John Weaver inspired several generations of dancers and choreographers including Gasparro Angiolini and Jean-Georges Noverre. For more information see John Weaver, An Essay Towards an History of Dancing, in which the Whole Art and its Various Excellencies are in Some Measure Explain'd : Containing the Several Sorts of Dancing. (London: Jacob Tonson, 1712).

- 3. Jennifer Homan, Apollo’s Angels A History of Ballet (New York: Random House, 2010), p. 56.

- 4. Kellom Tomlinson was an English dancing master, choreographer, and dance writer. His famous book, Art of Dancing was published in 1735.

- 5. Pygmalion was Marie Salle’s most famous ballet. The composer was Jean-Joseph Mouret. Goddess of Love, Aphrodite brings a statue of a women to life after the King of Cyprus, Pygmalion, carves statue of his ideal woman and falls in love with its likeness.

- 6. Ballet D’Action is a term created by Jean-Georges Noverre as part of his theatrical dance reforms. Noverre stressed the removal of elaborate costumes, masks and unrelated movements to the plot and insisted on a linkage of expression, choreography, libretto, costume, and scenery. Audiences found this format controversial and exciting.

Bodies’ Placement in the Theatre for Ballet Performances

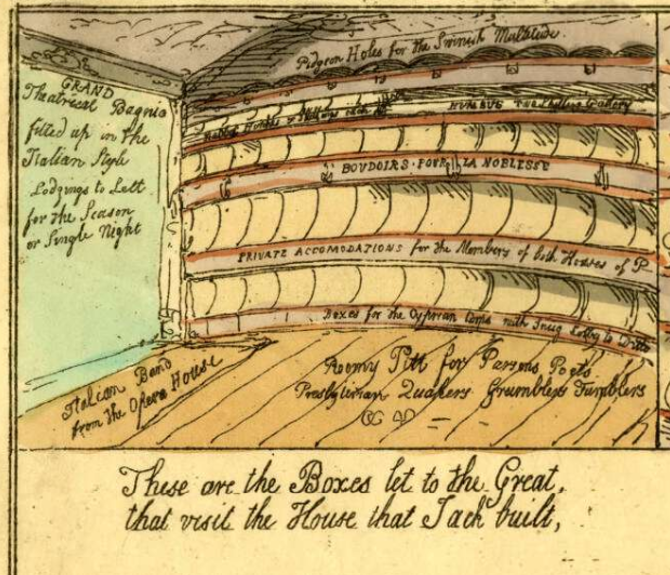

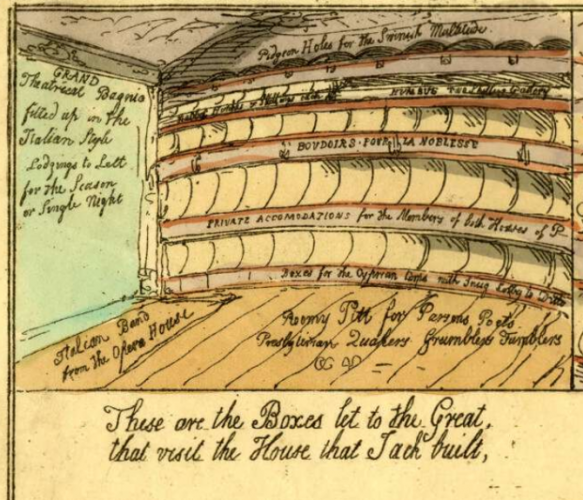

Within the interior of the theatre, the placement of the seated noble and gentry class attendees was a key part of the representation of one’s status. The space of the theatre and where bodies inhabited the space was dictated by the stage placement which was at the end of one side of the building. The titled and gentrified class of social status sat farther away from the stage, up higher in expensive theatre boxes, surveilling those below and around the space. Much interaction and gossip transpired during the performances about those in the audience and the dancers on-stage. The working class was left to the hodgepodge muddling and milling about in galleries, stalls or jammed into ‘Pidgeon Holes’.

Watching and interacting from their vantage point, they too chattered away adhering to their own social rules. It was not until the advent of gaslight that the noise of conversation in the theatre receded.

After the French and English War, more people began to come to see ballet performances including soldiers. Theatres relied on this rapt attention, discussion and debate about the content of the ballet, choreography, its performers, costumes, scenery, and music, to promote ticket sales, cover production costs, artistic fees and make a profit. The female danseuses’ silk encased legs and costumes, that revealed flesh was titillating and increased the male desire for conquest. Noted dance historian Ivor Guest describes ‘ballet as a man’s art’.7 Indeed, those lucky enough to be closest to the stage were often well-ranked moneyed men who greedily watched the dancers and fed their own desires to be seen by the audience. This group placement often obstructed the view of the audience and created a secondary semi-circle wall surrounding the dancers. On May 9, 1796, The London Times noted: ‘Mademoiselle Rose [Didelot], in throwing her fine muscular arms into a graceful attitude, inadvertently levelled three men of first quality at a stroke’ (Guest 20). Eventually this placement was discontinued based on the vociferous complaints of the audiences after the Gallery inhabitants ‘shouted abuse’ at the ogling crowd (Guest 20). Yet shouting approval, applauding wildly, demanding encores, and throwing flowers onto the stage (as audiences were wont to do) was not the only way that members of the public could express their enthusiasm for dance. They could also learn and dance some of the theatrical national dance steps seen onstage in the ballroom themselves, fitting foreign dance styles to their own bodies, much as they donned costumes to wear to public balls.8

Although Christian concepts of womanhood prevailed, stylish London ladies were inspired by the corset encased upper body and fancy costumes worn by the female dancers. They regularly ordered bright-colored gowns embellished with many decorations. The ensemble was completed by face framing hairstyles and jewelry. What one was wearing was part of the scrutinization and social discussion about others including the dancers. The staged fetishization of the female body was a vehicle for socially overt and hidden interactions, male audience members with female audience members, audience members, especially men, with female dancers on-stage, dancers on and off stage and patrons of female dancers.

Ballet Character Roles

The performers themselves portrayed a hierarchy on stage as ballet characters that John Weaver introduced to English audiences. By the early 1800s performers were segregated into categories: the danseur noble, demi-caractère and comique/grotesque. Each type of character role was danced by a dancer who presented a specific body type and skill. Only males performed the role of ‘danseur noble’ which portrayed princely characters. These dancers, with long proportional limbs and elegant aplomb, moved with gravitas and projected a sense of elegance in their movements, that was admired by the public. Shorter, muscular dancers portrayed ‘demi-caractère’ roles that required quick, dynamic, virtuosic air work like jumps or multiple turns around the body’s axis. This role was a less important character in the ballet, like a friend or merchant but often an audience favorite. Finally, the ‘grotesque or comique’ dancers performed roles such as villains, old men and women, clowns, or monsters. This caste system was rarely altered.9 The stereotypical hierarchy of bodies as commodities was reflected within society and on stage in its conceptions and rankings of human beauty.

- 9. Auguste Vestris was muscular and mid-size in stature. He was able to brilliantly perform all the ballet character roles thus his star power to draw audiences and subsequent discussion about him to the theatres. Giovanni-Andrea Gallini in his Treatise on the Art of Dancing (1772) notes’ ‘A tall person appears more majestic on it; [stage] but those of middling figure are more generally fit for every character; and may make up in gracefulness what they wont in size.’ This statement was not commonly seen on the stage.

The choreography of the ballets, often with ancient Greek themes in the late 1700s, created performative false sociability relationships on stage. This choreography displayed social values and ideals. Performers’ character portrayals and behaviors did not necessarily translate off-stage nor did it grant them admittance to high society. The dancers that portrayed the highest level of danseur noble or danseuse were the most sought after off-stage either as teachers and choreographers, or females for romantic relationships. The female danseuses were regarded by their fellow company artists with mixed envy, respect, and collegiality. However, there were often rival ballerinas competing for roles as well as for gentleman patrons. Relationships with patrons gave admittance into fringes of British high society. John Ebers, manager of the King’s Theatre and opera lover, sought to re-create the Paris Opera’s famous and fascinating ‘Foyer De La Danse’, a place men could visit to observe female dancers warming up and rehearsing for the performance. The purpose of the space was more for socializing and brokering than for rehearsing steps for the performance (See picture below). Ebers referred to the English version of this space, The Green Room.10

- 10. Ebers did not coin the term, Green Room. The roots of this term are unknown.

Jennifer Homans notes: ‘Onstage, ballerinas acted like aristocrats even when they were in real life most emphatically were not’ (Homans 64). In British society, female dancers’ bodies signaled, I am like you because my deportment and aplomb look like you or as you wish to appear. The dancer’s somatic confidence enticed the viewers’ interest, but on-stage portrayal was frequently dispelled during conservation at fashionable events, signaling that the dancer was not of their ilk. Unless one was a famous performer, most female dancers struggled to live on their income. After retirement from dancing, without support of a gentleman the living situation could become dire. Male danseurs, such as Anthony L’Abbé and John Weaver, had better options by becoming dancing masters or choreographers in retirement. Being a male in this occupation was a key to respectable success in ballet and society.

When thinking about the long eighteenth-century body and the spaces it inhabited, Hannah Arendt writes:

‘[…] the functionality and intersectionality of the body within these sociable ‘spaces of appearances’ of the theatre show the interconnectedness of the organizational strata, one level dependent on another for existence’, then adding ‘[…] where I appear to others as others appear to me, where men exist not merely like other living or inanimate things, but to make their appearance explicitly.’11

- 11. Maurizio Passerin d’Entreves, ‘Hannah Arendt’, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Fall 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/arendt/.

As theatrical, ticketed public spaces became more sociable and acceptable environments, both the stage and the audience mirrored one another. The stage, of prominent spatial importance, was an illusory and idealistic setting of sociability via the choreographed relationships of the dancers. The audience arena was a place of authentic corporeality. Both spaces and sociable interactions were unmistakable.

Share

Further Reading

Brooks, Lynn (ed.), Women’s Work Making Dance in Europe before 1800 (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2007).

Chazin-Bennehum, Judith, The Lure of Perfection: Fashion and Ballet, 1780-1830 (London: Routledge, 2005).

Franko, Mark, Dance as Text Ideologies of the Baroque Body (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Gallini, Giovanni-Andrea, Treatise on the Art of Dancing (London, 1772).

Homans, Jennifer, Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet (New York: Random House, 2010).

Noverre, Jean-Georges, Lettres sur la Danse sur la Ballets et les Arts, 4 vols. (St. Petersbourg: J.-C. Schnoor, 1803), vol. I.

Saltator [pseud.], A Treatise on Dancing and Various Other Matters (Commercial Gazette, 1802).