Abstract

The ancient city of Bath renowned for its waters ever since the Roman era played a decisive role in reinventing spa sociability in the first half of the eighteenth century. At a time when the British nation was being forged, manners were crucial in the rivalry with France, as they were redefined in an attempt to create a distinct model of sociability. In watering-places micro-societies emerged and interacted in modes that were the result of the paradoxical cohabitation of pleasure and pain, of illness and fashion. In Bath, sociability aimed at healing the citizen’s body together with the body politic.

The transformation of Bath in the long eighteenth century occurred against a background of urban, socio-economic, and scientific revolutions. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 ushered in a new political system, providing relative stability, which favoured the creation of a new image for the British nation.1 In a context of rivalry with France, the refinement of manners meant a degree of emancipation from the French model of politeness.2 The desire to change social behaviour was apparent in the aesthetics of novelty defined by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in The Spectator in which they celebrated the pleasures enjoyed by a man of a ‘polite imagination’ and asserted that ‘the pleasures of the fancy [were] more conducive to health than those of the understanding.’3 In their periodical, read by both men and women in places belonging to the public sphere and in those that were part of the private one, the role of women in the creation of a new model of sociability was acknowledged.4

Bath’s development and evolution from a centre of cure, whose waters had attracted invalids back in Roman times, to a centre of fashion were truly remarkable. A place of unruly, licentious behaviour in the seventeenth century, it became a centre of mixed sex sociability, ranking just behind London, as a beacon of new social interaction. A city which started as a market town5 evolved into a fashionable spa whose model of sociability was not simply imitative of the capital but also contributed to the shaping of the nation, so much so that it exported some of the attributes of spa sociability to the rest of the kingdom and beyond, in an age nicknamed the ‘age of watering-places.’6

Taking the Bath waters

In the eighteenth century, taking the waters did not simply mean bathing but it also involved drinking them (Cossic, Bath, 31-32).7 The Pump Room, originally a rather rudimentary establishment, became the rallying point of Bath visitors, a place where medical treatment was inextricably linked with conversation and where paradoxically illness became an agent of sociability.8 Discussing one’s illness was a way of reappropriating one’s body and of accepting it: it was part of a shared experience, even if not all ailments could be publicly discussed, in particular, gynaecological disorders.9 Nonetheless, talks in the Pump Room did not only revolve around health matters or gossip, the ‘Bath chat,’10 but could also take in their stride political issues11 such as the appointment of a new Prime Minister, or the Stamp Act crisis (1765-66).12 This newly formed community of invalids could temporarily ignore class divisions, at least the boundary separating the aristocracy and the gentry from the emerging middle class, or ‘middling orders.’

Some diseases could be seen as so many badges of honour, most particularly gout, considered as a ‘patrician malady.’13 At the turn of the century, Bath’s most famous visitor was Queen Anne whose stay contributed to its fame and kick-started its fashionable character. Its different baths had distinct medicinal properties and were frequented according to one’s ailments.14 Some were exclusively reserved for the upper reaches of society such as the Cross Bath, or the Cold Bath – a private bath,15 others were more mixed as was the King’s Bath. Later in the century the Duke of Kingston’s Baths were more exclusive.

Sociability was not simply the logical consequence of a prolonged stay – the cure was meant to last three weeks (Cheyne, Gout, 62-75) and there were eventually two seasons, Spring and Fall – it was part and parcel of the treatment. Entertainment was prescribed by the Bath doctors as an antidote to a well-known English malady that was caused by – or caused – different sorts of physical ailments. George Cheyne, who settled in Bath, advocated the virtues of ‘entertaining amusement,’ provided it was ‘innocent,’16 while Dr Oliver in his Dissertation on Bath Waters saw ‘same-sex socializing […] as part of a health regime.’17

The reinterpretation of the ideal of civitas

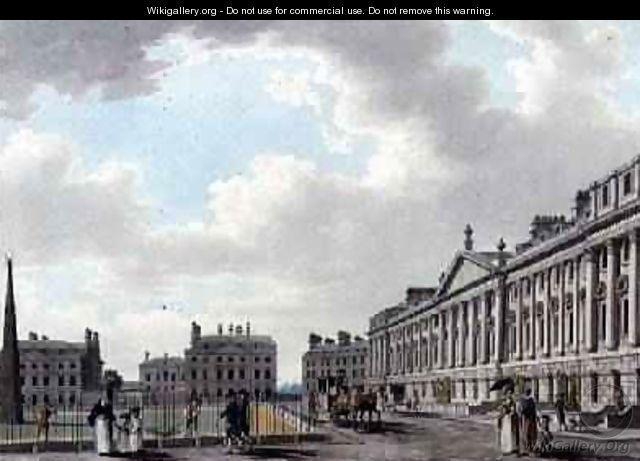

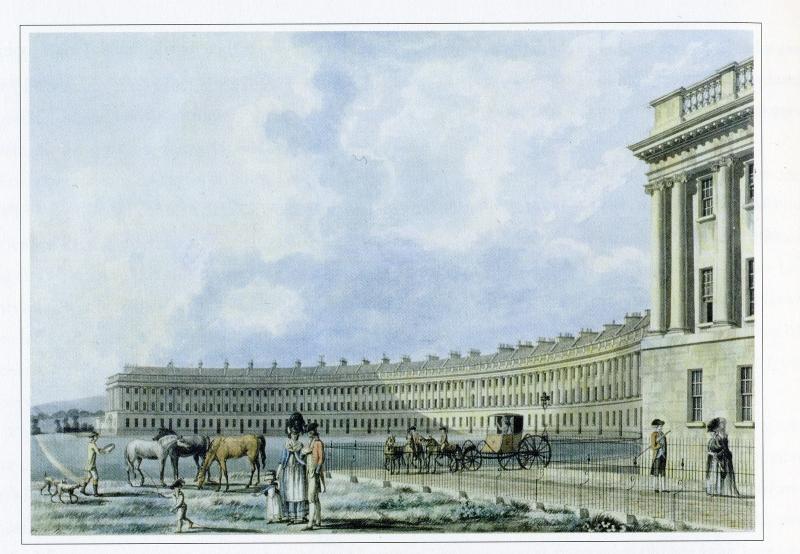

As sociability was central to the therapy, even if the suffering body is not sociable, it was rejuvenated in Bath in a holistic approach to city life in which architecture played a decisive part. The environment was redesigned with new spa attributes, the Assembly Rooms, the Pump Room, the King’s Bath, The North and South Parades, Orange Grove, new pleasure gardens, the Spring Gardens, airy streets conducive to social encounters and shopping, such as Milsom Street (one can think of its influence on the plots of some of Jane Austen’s novels, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion). In this respect, John Wood the Elder and his son John Wood the Younger were pioneers in their conception of the ideal city where the environment fashions a new spirit and encourages new social behaviour. Father and son envisioned a city where a new virtuous citizen could be born, thus reinterpreting the ideal of civitas, adapting it from the Roman ideal of civic virtue.18 They were convinced that Palladianism, with the simplicity of its lines, could contribute to the refinement of social behaviour and attempted to create ‘well-regulated’ places not simply as part of the health establishment but also in dwellings where individual houses were hidden under unifying fronts which made them resemble aristocratic palaces. This appears in Queen Square with its deceptive appearance of a single unit. Such an undertaking chimes in with the refinement of manners at work in the spa, since, as explained by Lawrence Klein, politeness had a ‘moral potential’ and ‘manners were the foundations of civic politics.’19

The Woods designed buildings that were then unique and were later duplicated in spas and seaside-resorts: the King’s Circus (1754) and the Royal Crescent (1776) can be considered as their most outstanding achievements. The circularity of their forms encouraged a leisurely stroll, symbolized perfection but also claimed a long-forgotten Celtic past (Cossic, Bath, 64-74). In their own way, the Woods participated in the forging of the nation. They were aware, like Ralph Allen, the City Mayor in 1742 and also a visionary entrepreneur, of the new needs of the emerging middling orders, and sought, through their elaboration of a beautiful environment, to refine manners. The Crescent encourages a winding walk and its semi-circular lines contrast vividly with the rectilinear ones of the industrial city.20 The theatricality inherent in spa life, where to see and to be seen was of paramount importance, and where illness was staged and invalids turned into ‘actors of their diseases’ (Cossic, Spas, 129),21 was the logical consequence of both the new buildings and the spa way of life.

The ideal of civitas prevailed in Bath until the middle of the eighteenth century: those who, together with the Woods, created a new image of the city – Beau Nash, a few Bath doctors, Ralph Allen, in Prior Park – tried to promote a utopia, that of Bath as a prime example of a new, open society.22 In Bath, different social classes were brought together by shared illnesses, so a shared condition of frailty, and the cult of novelty. The eleven rules of behaviour invented by Beau Nash and stuck in The Pump Room in 1707 aimed at getting rid of an aristocratic code of conduct where duelling was approved and the wearing of boots for gentlemen and of aprons for women on social occasions accepted. They replaced it with a new code of conduct including the ‘visit of ceremony,’ which was the very first of the eleven rules: 'THAT a Visit of Ceremony at coming BATH, and another at going away, is all that is expected, or desired by Ladies of Quality and Fashion; --- except Impertinents.'23 Beau Nash, as arbiter of good manners and taste, the Woods, as interpreters of Palladianism, tried to eliminate conflict from the spa through the implementation of a ritual and encouraged the harmonious cohabitation of the sexes and of the middling orders with high society, often termed the ‘Quality.’ The refinement of manners undertaken under Nash’s aegis seems to have outlived his reign as the diarist Katherine Plymley wrote in October 1794: 'The characteristic of Bath manners appears to me courtesy.'24

The evolution of the Bath model of spa sociability

Yet the ideal of the harmonious cohabitation of the different social classes and of the two sexes, with a concomitant politics of conflict avoidance, was seriously tarnished by the excesses of the leisure industry (Klein, 'Politeness and the Interpretation', 879). As Katherine Plymley stated in her diary on 27 October 1794: ‘The great business of this place is pleasure, life, I think, is seen through a false medium’ (Bath History IV, 101). Sociability itself was exploited, became a business and the ever-increasing popularity of Bath contributed to its decline. This is corroborated by the skyrocketing number of visitors from 400 people in 1760 to 4,000 in 1794 (Cossic, Bath, 85). Its transient sociability could turn out to be ambivalent, both drug and poison, a pharmakon, and ‘the queen of watering-places’ became the playing field of opposed forces, both centrifugal and centripetal. In letters and in fiction, Bath could be celebrated for its sociability or conversely lambasted for the poor quality of its conversation, in particular by ladies of fashion (Kerhervé 281-284). In the middle of the century and in its second half, Bath was represented in a satirical manner, by Christopher Anstey (The New Bath Guide, 1766) and Tobias Smollett (The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, 1771). Jane Austen, who spent some time in Bath, resented the superficial character of its social life and in Persuasion her heroine Anne Elliot, on arriving there, thought that she disliked the place.

- 1. See Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (London: Vintage, 1996), p. 381-398.

- 2. Lawrence Klein considers that politeness was ‘a flexible device for characterizing and regulating the period’s innovations in the forms of sociability,’ in ‘Politeness and the Interpretation of the British Eighteenth Century,’ The Historical Journal (vol. 45, n°4, 2002), p. 898.

- 3. Erin Mackie (ed.), The Commerce of Everyday Life, Selections from The Tatler and The Spectator (Boston: Bedford St Martin’s), The Spectator n° 411.

- 4. In n° 11, Steele creates the character of Arietta who embodies the virtuous female character promoted by the periodical, a foil to disturbing female figures such as the amazon, or the bar tender.

- 5. See Annick Cossic, Bath au XVIIIe siècle: Les fastes d’une cité palladienne (Rennes : Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2000), p. 21-34.

- 6. The number of British spas kept increasing: see Phyllis Hembry, The English Spa (1560-1815): A Social History (London: The Althone Press, 1990): over 138 spas were identified.

- 7. The practice became widespread in Bath following the publication of Dr William Oliver’s A Practical Dissertation on the Bath Waters (1704).

- 8. See Annick Cossic-Péricarpin, ‘Fashionable Diseases in Georgian Bath: Fiction and the Emergence of A British Model of Spa Sociability,’ Fashion and Illness in Eighteenth-Century and Romantic Literature and Culture, ed. Anita O'Connell and Clark Lawlor, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies (vol. 40, n° 4, 2017), p. 542-543.

- 9. Rose Alexandra McCormack points this out in her article ‘Female Health at the Eighteenth-Century Spa’, Fashion and Illness in Eighteenth-Century and Romantic Literature and Culture, p. 560. Also, Sander L. Gilman, Health and Illness: Images of Difference (London: Reaktion Books, 1995), p. 57: ‘sterility’ was perceived as a ‘social disease.’

- 10. Alain Kerhervé has shown the role of letters in the circulation of spa gossip between friends: ‘Writing Letters from Georgian Spas: The Impressions of a Few English Ladies,’ in Annick Cossic and Patrick Galliou (eds.), Spas in Britain and in France in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2006), p. 280.

- 11. See Sophie Vasset, ‘Pump Room Politics and the Murky Past of Spas,’ Murky Waters: British Spas in Eighteenth-Century Medicine and Literature (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022), chapter 4.

- 12. This is recorded in fiction, as for instance in Christopher Anstey, The New Bath Guide [1766], ed. Annick Cossic (Bern, Oxford: Peter Lang, 2010), letter IV, l, p. 19-35.

- 13. The phrase is used by Roy Porter and George Rousseau in their book, Gout: The Patrician Malady (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998).

- 14. George Cheyne drew up a list of affections likely to be cured by the Bath waters in An Essay on the True Nature and Due Method of Treating the Gout [1720] (London: A. Strahan, 1753), p. 62.

- 15. John Wood, A Description of Bath [1742] (Bath: Kingsmead Reprints, 1969), p. 259-268.

- 16. George Cheyne, The English Malady: or a Treatise of Nervous Diseases of all Kinds (London: G. Strahan, 1733), p. 181.

- 17. Amanda E. Herbert, ‘Gender and the Spa: Space, Sociability and Self at British Health Spas, 1640-1714’, Journal of Social History, (vol. 43, n° 2, Winter 2009), p. 362.

- 18. For its conception by Shaftesbury and Chesterfield, see Philip Ayres, Classical Culture and the Idea of Rome in Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 48.

- 19. Lawrence Klein, ‘Liberty, Manners, and Politeness in Early Eighteenth-Century England’, The Historical Journal, (vol. 3, n° 32, 1989), p. 588-592.

- 20. See Jacques Carré, Urbanisme et Société en Grande-Bretagne, 19e-20e siècles, Actes de colloque, (ed.) Jacques Carré et Monique Curcurù (Clermont-Ferrand: Adosa, 1988), p. 5-9.

- 21. For James Makittrick Adair in his essay, Medical Cautions, for the Consideration of Invalids; Especially those who Resort to Bath (Bath: Cruttwell, 1876), p.vi, to be fashionable is ‘to be known and to be seen.’

- 22. See Neil McKendrick, 'Introduction', in The Birth of a Consumer Society. The Commercialization of Eighteenth-Century England, ed. N. McKendrick, J. Brewer and J.H. Plumb (London: Europe Publications, 1982), p. 9-33.

- 23. Visiting was an essential feature of Bath's social life: see Letters from Bath, 1766-1767 by the Reverend John Penrose, (ed.) Brigitte Mitchell & Hubert Penrose (Gloucester: Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, 1783), p. 27.

- 24. Bath History, vol. IV (Bath: Millstream Books, 1992), Ellen Wilson, ‘A Shropshire Lady in Bath, 1794-1807’, p. 101 (Shropshire Record Office, Shrewsbury: Corbett of Longnor Papers).

Thomas Rowlandson’s prints The Comforts of Bath (1798) have provided a dark and humorous view of Bath’s social life that contrasts with Thomas Malton’s watercolours which enhance the magic of its bucolic scenery.25

Spa life in Bath was based on openness and revolved around the concepts of healing and encounter – in which ‘the participant has to mount a performance which can match the standards set by the jointly negotiated working consensus of the encounter’.26 Spa sociability was paradoxical: in a place sarcastically nicknamed by Tobias Smollett ‘the hospital of the nation’ it imposed beauty and pleasure on suffering distorted bodies and the less afflicted members of the travelling family who could also take the waters preventively. As a matter of fact, what brought the sick and the healthy together was an elusive quest for happiness and well-being. The essence of sociability is the unique combination of freedom – the freedom to choose one’s friends – and pleasure – the pleasure of association. In Bath, the stay could also involve a degree of emancipation: for women, temporary emancipation from the patriarchal model of sociability, from the prescriptions of the male doctors (Cossic, Spas, 115-139), for young sons, emancipation from authority. There, women, for a while, enjoyed more freedom than at home and could find friends or husbands: they escaped the confines of the family house, could go to such an innovative institution as a coffee-house for the ladies27 and enjoy the pleasures of the imagination to the full, thanks to the varied cultural life there (Cossic, Bath, 97-113) or simply the round of entertainments.28 This interpretation of the Bath sociable experience is corroborated by Miles Ogborn’s contention in Spaces of Modernity that some eighteenth-century places were sites of identity formation.29

- 25. Haydn wrote in his notebook that ‘Bath was one of the most beautiful cities in Europe’. See Howard Chandler Robbins Landon (ed.), Haydn in England, 1791-1795 (London: Thames & Hudson, 1976), p. 266.

- 26. Adam Kendon, Conducting Interaction: Patterns of Behavior in Focused Encounters (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 4.

- 27. See The Letters of Elizabeth Montagu, ‘Bath, to the Duchess of Portland, 27 December 1740’, vol. I, p. 72-73; also Rose Alexandra McCormack, ‘Female Health,’ p. 562.

- 28. See for instance, ‘The Journals of Mrs Philip Lybbe Powys (1738-1817) A Half Century of Visits to Bath,’ in Stephen Powys Marks (ed.), Bath History (Bath: Millstream Books, 2002), vol. IX, p. 60.

- 29. Miles Ogborn, Spaces of Modernity: London’s Geographies 1680-1780 (New York, London: The Guildford Press, 1998) p. 42. The extension to spa sociability is made by Amanda Herbert in ‘Gender and the Spa’, p. 372.

The model of urban sociability that was in the making in Bath was more conducive to empowerment, be it of short duration, than the rural counter-model of retirement, even if it was also far less secure, as demonstrated by countless real-life stories, among which that of Fanny Braddock, a prey to gambling, whose social downfall led to her ostracization and ultimately suicide, as narrated by John Wood (Wood 451). Spa sociability departed from standard urban sociability in that health was central to it: spa visitors did not always avoid the pitfall of dependency on drugs in a place where water alone should have been the bulk of the therapy, or, equally damaging to their health, that of excess. If, as shown by Cheyne, ‘civilisation created sickness,’ and ‘the progress of civilisation proved the progress of sickness,’30 then sociability in Bath could both cure and kill.

- 30. Roy Porter (ed.), The English Malady (1733) (London and New York: Tavistock/Routledge, 1991), p. xxvii.

The Bath model of sociability knew its heyday in the first half of the eighteenth century. In the second half, the legacy of Bath’s most famous Master of Ceremonies, Beau Nash, faded away. Social life in Bath no longer revolved around social occasions in Assembly Rooms or in open spaces such as Pleasure Gardens where public breakfasts or tea could be organized; public tea for instance was given by the Duke of Cumberland in April 1767: ‘the Sunday evening he gave public tea to all, townspeople as well as strangers. You may depend upon it he wanted not company’ (Penrose 164). Sociability took on a more intimate turn with the development of private parties, ‘the bane of Bath.’31 Elite women organized social gatherings in their homes, or poetic assemblies: this is what Lady Miller did in her Batheaston Villa, near Bath between 1774 and 1781, an undertaking that was unique then and imitated later elsewhere.32 Georgian Bath’s founders’ utopian attempt at keeping away conflict and thereby politics was bound to fail. In this respect, Bath was no exception to the rest of the kingdom and could not escape class wars, apparent in the Gordon Riots of 1785 (Cossic, Bath, 160), and the new trend towards mass mobilization, as demonstrated by the actions of Hannah More and William Wilberforce. Hannah More, for her part, used her Bath connections for philanthropic and political ends – in particular in her fight against the French Revolution –, be they the alleviation of poverty or the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade.33 She thus sketched out a different model of female sociability based on usefulness, a sort of useful sociability, a sociability of the heart.

- 31. William Hadley, A Poetical Address to the Ladies of Bath. Or Shoot Folly as it Flies (Bath: R. Cruttwell, 1774), p. 11.

- 32. See Transversales vol. 2, Annick Cossic-Péricarpin, ‘The Batheaston Literary Circle’s Poetical Games (1774-1781): from the Imitation of French Bouts-Rimés to the Creation of an Innovative Pattern of Sociability’ (Paris: Le Manuscrit, 2013), p. 231-261.

- 33. Hannah More in a letter to the Rev. Joseph Berington, Barley Wood, 1809, described her sociable use of her Bath house, a place which ‘for many winters was constantly open to as many as resided there.’

Sociability in Bath partly fitted in with Georg Simmel’s definition which put the emphasis on freedom and pleasure.34 Pleasure was certainly there for those suffering from fashionable diseases or for those that accompanied invalids, wonder too as Bath was fairly unique in the first half of the century. Yet the type of sociability that it favoured – public and open – contained the seeds of its decline. The egalitarian aspect – although balls for instance were extremely codified and the minuet reserved for the Quality while country dances were for the rest of the assemblies – was very deceptive. The mixing of classes in the baths or in the Pump Room was a one off, not to be duplicated elsewhere, in the ‘real world.’ A tension emerged very quicky between the desire of local entrepreneurs to make the spa industry profitable, thus encouraging speculative ventures, and the class-consciousness of its most privileged patrons eager to stick to their own sociable circles, spaces and codes.

- 34. Georg Simmel, Sociologie et épistémologie, trad. L. Gasparini (Paris : Presses Universitaires de France, 1981), p. 125.

The model of its open sociability was difficult to export to London or to regional capitals because a spa experience is somehow defined by its transiency and cannot be duplicated in a city with a different economy and possibly a different geography. Its ephemeral character, its relative suspension of time, and its well-heeled daily routine were what made it valuable and were part of its magic appeal. The industrial city in Britain developed along different lines and gave birth to a different type of sociability. To this limited impact of spa sociability must be added the growing competition from seaside resorts, such as Brighton,35 which accelerated the transformation of Bath into a residential city with private parties taking over from public ones, as shown by the case of the Elliots in Persuasion who went to Bath to settle permanently, to the despair of Anne Elliot, the middle daughter of the family. The exploitation of its Roman and Georgian pasts became an industry, attracting countless tourists from various parts of the world, as Bath was awarded the label of World Heritage City. In recent years, the therapeutic dimension of a Bath stay has been resuscitated and the Bath thermal establishment given a new lease of life, as Thermae Bath Spa.

- 35. See Transversales vol. 7 (Paris : Le Manuscrit, 2021) : Elaine Chalus, ‘Espaces de sociabilité dans la haute société : Brighton (1825-35)’, p. 215-237.

Share

Further Reading

Borsay, Peter, The Image of Georgian Bath 1700-2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Chalus, Elaine, ‘Elite Women, Social Politics, and the Political World of Late Eighteenth-Century England,’ The Historical Journal (vol. 43, n° 3, September 2000), p. 669-697.

Eglin, John, The Imaginary Autocrat: Beau Nash and the Invention of Bath (London: Profile Books, 2005).

Herbert, Amanda, ‘Hot Spring Sociability: Women’s Alliances at British Spas,’ Female Alliances, Gender, Identity and Friendship in Early Modern Britain (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014), p. 117-142.

Poole, Steve, ‘Radicalism, Loyalism and the “Reign of Terror” in Bath, 1792-1804,’ in Simon Hunt (ed.) Bath History, vol. III, (Gloucester: Alan Sutton, 1990), p. 114-138.

Pope, Cornelius, The New Bath Guide; Or Useful Pocket Companion [1762] (Bath: Pope, 4th edition, 1766).

Porter, Roy, ‘Civilisation and Disease: Medical Ideology in the Enlightenment,’ in Jeremy Black and Jeremy Gregory (eds.), Culture, Politics and Society in Britain, 1660-1800 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991), p. 165.

Rolls, Roger, The Hospital of the Nation. The Story of Spa Medicine and the Mineral Water Hospital at Bath (Bath: Bird Publications, 1988), chapter 8.

Walton, John K. (ed.), Mineral Springs Resorts in Global Perspective: Spa Histories (London: Routledge, 2014).