Abstract

For two decades, George Bryan Brummell, the archetypal dandy, exercised his power, frequenting London’s elite clubs, balls, and dinners. Not only did he introduce a new clothing style for men, based on clear lines, a sparing use of colours other than black and white, and little ornament, but he also created eagerly absorbed rules about comportment in society. The fascination with the historical Brummell also led to numerous, more-philosophically-oriented essays and books about this cult figure. If the historical Brummell was an immensely sociable figure, later writers such as Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly and Charles Baudelaire turned him into a mythical icon.

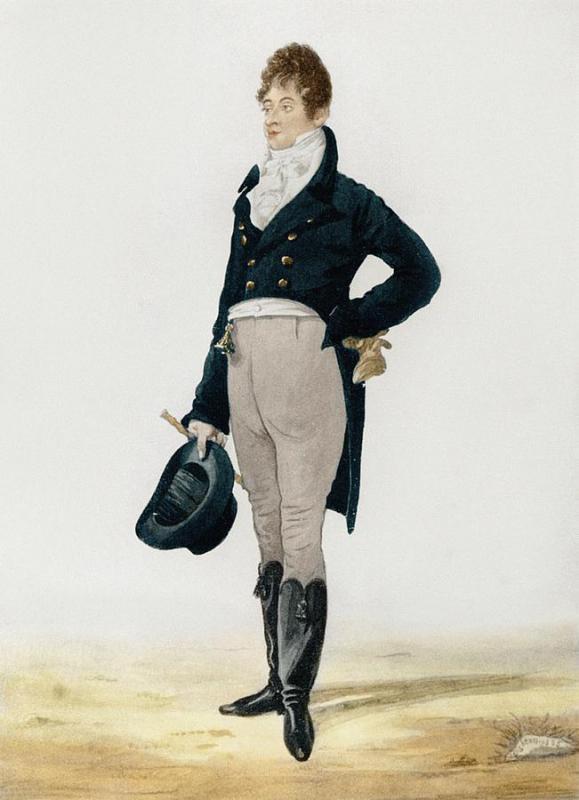

Until today, George Bryan ‘Beau’ Brummell (1778-1840) is credited with being the first, the ‘Ur’-dandy. Moving in London’s top aristocratic circles and clubs, being at the very centre of Regency society, the dandy-socialite was renowned for his elegant clothing style, his supposedly infallible judgement on all matters linked to dress and comportment, and his epigrammatic and often insolent sayings. He enjoyed immense power for over twenty years, from the time he joined the fashionable Tenth Regiment in 1794 up to his final departure from England in 1816. Like the fop, the buck, and the flâneur, the dandy is a fashionable embodiment of masculinity. As a type or a pose, he gained currency in the nineteenth century. Young men were quick to copy Brummell’s elegant dressing style and mannerisms, already at a time when he was still acting as the acknowledged arbiter of taste.

Brummell rose to prominence among London’s social elite very quickly. Although not born into one of the great aristocratic families, he came from a well-to-do background. His father being private secretary to Lord North, George grew up playing with children of neighbouring aristocratic families, was sent to Eton, and spent nearly a year at Oxford in 1793/94. The friendships he struck up in those years remained important for him throughout life. After leaving Oxford, he accepted a cornetcy in the Tenth Regiment, the Prince of Wales’s cavalry regiment, which was famous for its elegant officers, many of whom came from wealthy aristocratic families. The Tenth was usually busy in Brighton or London and had representative rather than military functions, for example, escorting.1 Brummell remained there until 1798. For him, the sociable side of being a soldier superseded any military activities. He was a close companion of the Prince Regent’s, attended parties, and began to cultivate his own fashionable style as well as his famous and cheeky witticisms. When for example the Duke of Bedford wanted an opinion about a coat, Brummell scrutinized him ‘from head to foot’ (Jesse I: 63), made him turn round, felt the cloth with his fingers, and then ‘in a most earnest and amusing manner’ exclaimed: ‘Bedford, do you call this thing a coat?’ (Jesse I: 63). The anecdote exemplifies the importance of taste (the search for the ‘right’ item of clothing), Brummell’s immense power (a duke begging a commoner for a judgement of taste), and his brash, cheeky style of speech (manifested through a reply calling the duke’s power of judgement into question).

Subsequent to leaving the regiment, Brummell, the Prince Regent’s friend and part of the Carlton House set, became an immensely powerful figure in London’s leading circles of the bon ton, the fashionable world. He could make and break reputations. That the court failed to fulfil its role as a centre of power during the Regency years facilitated Brummell’s ascent. Among his arenas of sociable interaction were clubs, balls, parks, theatres, and the streets of Mayfair. Brummell was a member of White’s and Brook’s, old and exclusive London clubs, and a founding member as well as president of Watier’s, a club reputed to serve the best dinners in London. If later writing emphasizes the dandy’s uniqueness and even solitude, the historical Brummell was extremely sociable, spent his days communicating but also cultivated aloofness, as the following anecdote shows: together with other dandy friends, Brummell ‘held court’ (Kelly 150) in the bow window of White’s, commenting on the day’s events. Thereby they created an unofficial, select club within the club, which apparently no other member of White’s dared to join uninvited. This ritual situated Brummell at the centre of White’s, while simultaneously setting him apart from ordinary members; the ‘club within the club’ symbolically expresses the exclusiveness of the bon ton. Among the institutions Brummell frequented was also Almack’s, an assembly room devoted to dancing (Kelly 179-181), only open to a very select audience, where he helped the patronesses to decide who was granted admission. According to Jesse, a debutante on her first visit to Almack's, a duke's daughter, was pressed by her mother to make ‘a favourable impression’ on Brummell, who was influential enough to define the boundaries of good society (Jesse I: 99; Kelly 181-182).

For contemporaries, Brummell’s verbal style was a central element of this performance. In Regency London, a few hundred families belonged to good society, following its often very elaborate formal rules. By questioning hierarchies while assuming a position of power, Brummell was playing a paradox game. Despite his brash comments, his biographer Jesse credits him with the ‘art of pleasing’ (I: 119); Brummell also possessed the gift of making friends. Jesse’s biography frequently references Brummell’s ‘album’, a book into which the great dandy himself entered poems written to or about him, a document of his sociable circle, with verse from a range of people, among them Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Lord Erskine, Lord Byron, and Lord John Townshend. A darker aspect of his sociable interaction is that Brummell also had a reputation for dropping friends who were no longer useful to him (Jesse I: 38).

- 1. My entry is indebted to two biographies in particular: Brummell’s first biography by his contemporary Captain Jesse and Ian Kelly’s modern study: Captain Jesse, The Life of George Brummell, Esq., Commonly Called Beau Brummell, 2 vols. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1844); Ian Kelly, Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Man of Style (New York: Free Press, 2006). For the regiment see Kelly, p. 57-58.

One of the pillars on which Brummell’s celebrity status rested was his insolent wit. Unspectacular questions led to highly provocative replies from him, which quickly gained currency as anecdotes and circulated among the bon ton. Being bored by a visitor, who enthused about the Northern lakes, Brummell, when asked which one he preferred, snubbed his guest by turning to his valet. The following dialogue ensued: ‘Robinson’. ‘Sir’. ‘Which of the lakes do I admire?’ ‘Windermere, sir’, replied that distinguished individual. ‘Ah, yes, - Windermere’, repeated Brummell, ‘so it is – Windermere’. (Jesse I: 118). When, according to Jesse, a planned elopement with a lady failed through being discovered, he pretended to have lost interest in her because she ‘actually ate cabbage’ (I: 125-126, quotation 126). Brummell’s unforeseen replies often comically point at a lack of style, comportment, or judgement. Brummell simultaneously played with and inverted the rules of polite conversation: he implicitly demanded verbal precision, brevity, and style, but used others’ errors or clumsiness to make them the butt of his jokes. It is not clear when exactly and why he lost the Prince Regent’s friendship. Although they never fell out officially, Brummell’s insolent demeanour may have been one reason; another was that he incurred the dislike of Mrs Fitzherbert, the Prince Regent’s secret spouse; moreover, the prince was inconstant in his friendships. One day Brummell, ignored by the prince, inquired from a person standing close by: ‘Who’s your fat friend?’ (Jesse I: 274), thereby hardly endearing himself to his former protector.2 William Hazlitt, who collected some of Brummell’s sayings, viewed them with scepticism; it also seems that once the dandy had fallen from his pedestal, fewer people considered his epigrammatic statements funny.

- 2. Many of these insolent replies are taken up by Jesse and Kelly. See also William Hazlitt [and (?) Leigh Hunt], ‘Brummelliana,’ in Duncan Wu (ed.), New Writings of William Hazlitt, vol. I / II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 326-333.

The area where Brummell left a lasting impact was the realm of men’s fashion.3 He paid scrupulous attention to every detail of his appearance. Tony Lynch has emphasized that the question is not how Brummell dressed but ‘how he didn’t dress’.4 Brummell refrained from ornate styles, textiles in bright colours, lace, ornaments, jewellery, powder, and other elements of eighteenth-century male fashion, or he used them very sparingly. Clarity and radical simplicity were the main ingredients of his own elegant style, which led the fashion for men. His preferred colours were white or cream and black; blue and buff-coloured cloth was acceptable, too. The cut of his clothes emphasized proportion and the muscular body. One of his hallmarks was a slightly starched, folded white neck-cloth, hard to copy but nevertheless imitated by aspiring dandies. The snuff-box, one of the few accessories Brummell allowed, became a cult object among the fashionable. These details, Roland Barthes has argued, served to signal social difference.5

- 3. For a survey see Kelly (91-108); Dita Svelte, ‘“Do You Call This Thing a Coat?” Wit, the Epigram and the Detail in the Figure of the Ultimate Dandy, Beau Brummell’, Fashion Theory (vol. 22, n° 3, 2018), p. 259-261.

- 4. Tony Lynch, ‘The Heretical Romantic Heroism of Beau Brummell’, European Romantic Review (vol 27, n° 5, 2016), p. 682.

- 5. Roland Barthes, ‘Dandyism and Fashion’, in Andy Stafford and Michael Carter (eds.), The Language of Fashion (London: Bloomsbury, 2004), p. 60.

Although Brummell’s declining power is linked to the loss of the Prince Regent’s friendship, his lifestyle also contributed to his ruin. Accumulating gambling debts, he hastily left England in 1816 to avoid arrest. Withdrawing to France, he lived in Calais between 1816 and 1830 and then in Caen, where he acted as British consul for less than two years. Due to his biographer Jesse, who visited him in France, this second half of Brummell’s adult life is well documented. Two major problems, lack of funds and debts as well as ill health, marked these years. If he received financial help from old friends in England, the disease, which Kelly assumes to have been syphilis (193), could not be kept at bay. Brummell continued to socialize in France with local citizens and was frequently visited by British travellers who wanted to see this living legend. He remained unmarried. Gradually, he became a tourist attraction: travellers stopping at the Hôtel d’Angleterre in Caen asked to be seated near him during dinner (Jesse II: 273). Brummell died on 30th March 1840 in Caen, after a prolonged and severe illness.

If the real George Brummel died on his own in 1840, his literary afterlife had already begun during his lifetime. Brummell-like figures, or dandies in a wider sense, appeared in numerous fictional texts: T. H. Lister’s novel Granby (1826), with its dandy Trebeck, which Brummell actually read, as well as Edward Bulwer Lytton’s Pelham (1828)6 portray dandy characters, as does Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). Leaving the historical Brummell behind, later dandies, be they literary or real, came to be associated with style, urbanity, a certain wealth, and bohemianism. Alongside the dandy’s fictional treatment, a more ‘dandy-philosophical’ strain of reception (Kelly 16) developed: Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly’s Du Dandysme et de George Brummell (1845)7 and Charles Baudelaire’s vision of the aloof dandy’s ‘culte de soi-même’8 as well as his self-assumed, quasi-sacerdotal function in Le Peintre de la Vie moderne (1863).

- 6. Thomas Henry Lister, Granby: A Novel, 3 vols. (London: Colburn, 1826); Edward Bulwer Lytton, Pelham; or, The Adventures of a Gentleman, 3 vols. (London: Colburn, 1828); Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (London: Ward, Lock and Co., 1891).

- 7. Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, Du Dandysme et de George Brummell (Caen: B. Mancel, 1845).

- 8. Baudelaire, Charles, ‘Le Dandy’, in Le Peintre de la Vie moderne [1863], Œuvres Complètes, 6 vols. (Paris: Conard, 1925), vol. 3, p. 89.

Share

Further Reading

Adams, James Eli, Dandies and Desert Saints: Styles of Victorian Masculinity (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995).

Beerbohm, Max, 'Dandies and Dandies', The Works of Max Beerbohm 10 vols. (London: William Heinemann, 1922), vol. I, p. 3-25.

Cole, Shaun, and Miles Lambert (eds.), Dandy Style: 250 Years of British Men’s Fashion (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2021).

Moers, Ellen, The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm (London: Secker & Warburg, 1960).

Pine, Richards, The Dandy and the Herald: Manners, Mind and Morals from Brummell to Durrell (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988).