Abstract

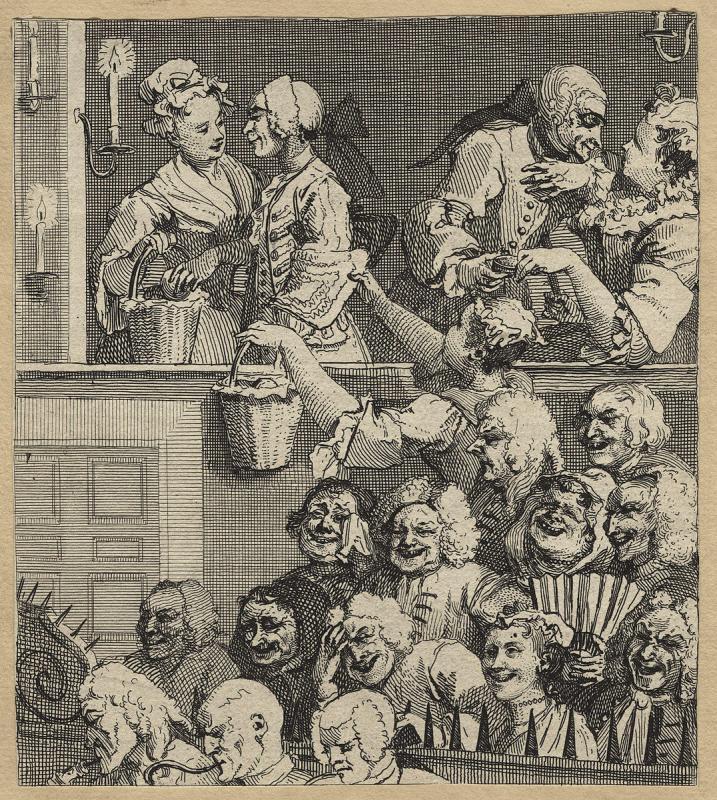

Laughter was considered fundamental to sociability in eighteenth-century Britain, but it was a complex social signal: as Samuel Johnson observed, ‘you may laugh in as many ways as you talk’. In its various guises, laughing could communicate anything from warmth to outright hostility; a well-placed chuckle could be the epitome of politeness, while an uncontrolled guffaw – especially triggered by a ‘lowbrow’ joke – was anything but. Laughter was scrutinised with vigour by notable thinkers and theorists of sociability; broaching issues of wit, sincerity, taste and bodily control, nothing exposes the anxieties and aspirations inherent in sociability quite like laughter.

Keywords

In May 1787, author-turned cleric Thomas Monro devoted an issue of his short-lived periodical to the topic of laughter. He cast it as one of the defining characteristics of human experience. Humankind, he wrote, ‘is a rational animal, a tool-making animal, a cooking animal’ and, crucially, ‘a laughing animal’. The chief importance of laughter, however, was in sociability: it was fundamental to sharing one another’s company, or as Monro put it:

Monro was far from alone in investing laughter with particular importance to social interaction in the eighteenth century; indeed, the social significance of human risibility was pursued with energy and fascination by some of the period’s most notable thinkers, from the third earl of Shaftesbury, to Francis Hutcheson, David Hume, and Mary Wollstonecraft.2 This discussion was shot through with ambivalence. Laughing could communicate anything from warmth to outright hostility; a well-placed chuckle could be the epitome of politeness, while an uncontrolled guffaw – especially triggered by a ‘lowbrow’ joke – was anything but. Broaching issues of wit, sincerity, politeness, taste and bodily control, nothing exposes the anxieties and aspirations inherent in sociability quite like laughter.

The problem was that not all laughs were created equal. The classificatory approach taken in eighteenth-century Britain was epitomised by William Brownsword’s Laugh Upon Laugh: or Laughter Ridicul’d (1740). It promised to account for ‘the several Kinds or Degrees of Laughter’, which he treated as a scale, moving from laughter’s most subtle varieties through to its heartiest:

- 2. Ross Carroll, Uncivil Mirth: Ridicule in Enlightenment Britain (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021).

Laughter involved a complex interplay of body and mind. It was a physical action – not quite a speech act, but nevertheless a noisy and corporeal intervention in social interaction – but it originated in the mind, motivated by certain thoughts, feelings, and mental processes. Laughing was always understood as a social signal, but its various guises could have different effects and were evaluated accordingly. As Samuel Johnson put it, ‘you may laugh in as many ways as you talk; and surely every way of talking that is practised cannot be esteemed’.4

- 4. James Boswell, The life of Samuel Johnson (London: Henry Baldwin, 1791), vol. 1, p. 244.

For those eager to theorise and encourage polite sociability, laughter was key. When well-placed, moderate, and inclusive, laughter would foster the mutually pleasing and genial relations to which politeness aspired. As the Scottish moral philosopher Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746) argued in his Reflections Upon Laughter:

It is often a great occasion of pleasure, and enlivens our conversation exceedingly, when it is conducted by good nature. It spreads a pleasantry of temper over multitudes at once; and one merry easy mind may by this means diffuse a like disposition overall who are in company.5

- 5. Francis Hutcheson, Reflections Upon Laughter (Glasgow: printed by R. Urie for D. Baxter, 1750), p. 32.

Shared laughter would nurture social accord. Smiles expressed affability and an ease of manner, while the ‘tee hee’ – or ‘titter’ to which Brownsword referred – was ‘the first laugh with voice’: it was a controlled show of amusement that would punctuate conversation in a polite assembly room. When targeted appropriately, laughter could also demonstrate and promote good taste – the ubiquitous aspiration of polite society. The German philosopher Georg Friedrich Meier (1718-1777) epitomised this sentiment in his 200-page exposition on the art of jesting, which noted:

As it is always an indication of a vitiated low Taste, either to jest in an insipid Manner oneself, or to approve the low, insipid Jests of others; and on the contrary, always Proof of a refined Taste, never to jest but in a sprightly Manner, and never to approve but sprightly Jests.6

In a society in which it was the worst of all social crimes to be considered a dullard, the capacity to jest appropriately, and laugh accordingly, was a fêted social skill.

- 6. Georg Friedrich Meier, The Merry Philosopher; or, Thoughts on Jesting, trans. Anon. (London: J. Newbery and W. Nicoll, 1764), p. 14.

In eighteenth-century intellectual circles, however, good humour and laughter were not simply a matter of superficial good manners; they were elevated as an essential prop to civil society. The third earl of Shaftesbury’s essay, Sensus Communis, or an Essay on the Freedom of Wit and Humour, was among the most prominent texts to make the case. For Shaftesbury, sociability needed ridicule and laughter: they were a constituent part of conversation and played a crucial role in sustaining peaceable co-existence in society. In particular, good humour facilitated serious discussion by allowing ideas to be debated and contested with geniality, and without descending into fractiousness. Moreover, well-targeted ridicule would refine manners and morals: laughing at another’s foibles would gently correct unsociable behaviour. In Shaftesbury’s words, ‘we polish one another, and rub off our Corners and rough Sides by this amicable Collision’.7 It was this deeper commitment to laughter’s role in sociability that underpinned Francis Hutcheson’s comments cited above. As a follower of Shaftesbury, it is no surprise that his Reflections Upon Laughter concluded that it ‘is plainly of considerable moment in human society’ (Hutcheson 32).8

- 7. Anthony Ashley Cooper, third earl of Shaftesbury, Sensus Communis, or an Essay on the Freedom of Wit and Humour’ in Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times (London, 1711), vol. 1, p. 64. On Shaftesbury, ridicule and sociability see Ross Carroll, Uncivil Mirth: Ridicule in Enlightenment Britain (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021), esp. chapter 2.

- 8. Kate Davison, ‘”Plainly of Considerable Moment in Human Society”: Francis Hutcheson and Polite Laughter in Eighteenth-Century Britain and Ireland’, Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement (vol. 88, 2020), p. 143-169.

Those advocating ridicule and laughter in sociability, however, rarely did so without reservation. This ambivalence was rooted in anxieties about laughter’s potential to communicate hostility. As Brownsword described, laughter was not all smiles and titters; there were grins, ‘smerks’ and sneers too, with the latter defined in Johnson’s Dictionary as ‘a look of contemptuous ridicule’ and ‘an expression of ludicrous scorn’.9 The notion that certain kinds of laughter communicated contempt dated back to antiquity, but it was given momentum and prominence by Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan (1651). For Hobbes, laughter was triggered by ‘Sudden Glory’: it was the grimacing joy we experience on perceiving ourselves as superior to the object of our laughter – the product of a gratified selfish ego.10 Hobbes’s account was much debated and disputed by later thinkers – not least Shaftesbury and Hutcheson – but laughter never entirely shook its potential to cause offence. As Hutcheson himself acknowledged, to be laughed at is ‘extremely provoking’ (Hutcheson 31).

Notwithstanding such expressions of contempt, impolite laughter was not necessarily a threat to sociability. Jesting literature and caricature alone testify to the period’s relish for humour that was distinctly unrefined, with sexual and scatological content aplenty, as well as references to race, ethnicity, disability and the destitute that jar profoundly with modern-day sensibilities. These kinds of materials were read and enjoyed socially.11 One jestbook, for example, sorted its jests under subtitles, including ‘Of Faces and Scars’ and ‘Of Crookedness and Lameness’, while the inside cover bore a picture of a rotund laughing gentleman, with a strapline emphasising the collective enjoyment the book offered:

- 11. Simon Dickie, Cruelty and Laughter: Forgotten Comic Literature and the Unsentimental Eighteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012); Vic Gatrell, City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London (New York: Walker, 2006).

That rude and cruel humour was a common occurrence in eighteenth-century sociability is reflected in reluctant acknowledgements of laughter’s theorists. Meier’s philosophical work sought to raise the standard of jesting, but he conceded that ‘Experience also teaches, that a set of merry people scarce ever meet together, but at last they fall into loose or smutty discourse’; he was forced to conclude that ‘what is indecent at one time, is not so at another’. In doing so, Meier reflected an important tenet of eighteenth-century conduct guidance, which held that appropriate behaviour depended on the contexts of time, place, and the nature of company. When socialising among familiar companions, bawdy jokes and hearty laughter were not just acceptable; they were celebrated (Meier 101).13 Indeed, by the later century, laughter in spite of polite strictures had become an issue of sincerity. Laughing was widely recognised as a natural and instinctive response to the humour of a moment: to suppress it could be construed as disingenuous. Hence discussions of laughter broached a wider critique of politeness on the grounds of artificiality.14

In eighteenth-century discussions, laughter encapsulated humankind’s natural inclination to be sociable, but it remained a complex social signal. It could grease the wheels of conversation, foster polite interactions, or prop up civil society at large, but it always had a latent power to disrupt and divide. For historians, there is no better prism through which to observe the ambivalences, intricacies, and aspirations at stake in the period’s sociability.

Share

Further Reading

Carroll, Ross, Uncivil Mirth: Ridicule in Enlightenment Britain (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021).

Davison, Kate, ‘”Plainly of Considerable Moment in Human Society”: Francis Hutcheson and Polite Laughter in Eighteenth-Century Britain and Ireland’, Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement (vol. 88, 2020), p. 143-169.

Dickie, Simon Cruelty and Laughter: Forgotten Comic Literature and the Unsentimental Eighteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Gatrell, Vic, City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London (New York: Walker, 2006).