Abstract

Falling into a long tradition of violent gatherings such as the Tityre Tu, the Bugles, or the Damned Crew, a group of ‘gentlemen’ called the Mohocks was rumored to have terrorized London’s streets in the Spring of 1712. While little evidence exists for the Mohocks being an organized group with a shared motif of mischief-making, rumors nevertheless put the violent outbursts attributed to them into the context of a club-like structure, thereby creating a curious case of asocial sociability. The inflamed public imagination thus provides an insight not only into the ways a nearly unregulated press could politicize such an issue, inciting a city-wide panic in the process, but also into the anxieties of eighteenth-century London, which, rather than revolving around utter chaos, center on an organized, debauched, and altogether darker twin of polite society.

Keywords

Historians have pondered the concomitant if not paradoxical entanglement of politeness and libertine behavior in the evolution of sociability from the Restoration to the long eighteenth century.1 Oftentimes, however, considerations regarding the influences of rakish behavior center predominantly on the sexual side of libertinism rather than its more violent aspects.2 The Mohock Scare provides an insight into that latter, more brutal facet of eighteenth-century rakishness, and how even the anxiety surrounding amoral and anti-social behavior is, in the public mind, ultimately framed through sociable codes such as organized club meetings and initiation rituals, providing a distorted, darker picture of London’s manner-focused society. In the Spring of 1712, the Mohocks ‘galvanized fears of the sort of street violence that was endemic in early modern London’ (Statt 179), eliciting contemporary responses ranging from the political to the literary, culminating in a royal proclamation on March 18th 1712, whereby Queen Anne issued a reward of one hundred pounds to aid in the discovery of a number of ‘evil-dispos’d Persons, who have combin’d together to disturb the Publick Peace, and in an inhuman manner, without any Provocation, have assaulted and wounded many of Her Majesty’s good Subjects’.3 While this proclamation had little noticeable effect – in his Journal to Stella (1712), Swift wrote afterwards: ‘Our Mohawks go on still, & cut Peoples faces every night’4 – it nevertheless speaks to the reach of the rumors surrounding the Mohocks, and how easily they penetrated even the royal court.

- 1. Brian Cowan, ‘”Restoration” England and the History of Sociability’, in Valérie Capdeville and Alain Kerhervé (ed.), British Sociability in the Long Eighteenth Century: Challenging the Anglo-French Connection (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2019), p. 19.

- 2. Daniel Statt, ‘The Case of the Mohocks: Rake Violence in Augustan London’, Social History (vol. 20, n° 2, 1995), p. 181.

- 3. The London Gazette, March 18th, 1711-12.

- 4. Jonathan Swift, Journal to Stella, ed. J. K. Moorhead (London: J. M. Dent & Sons LTD, 1955), p. 345.

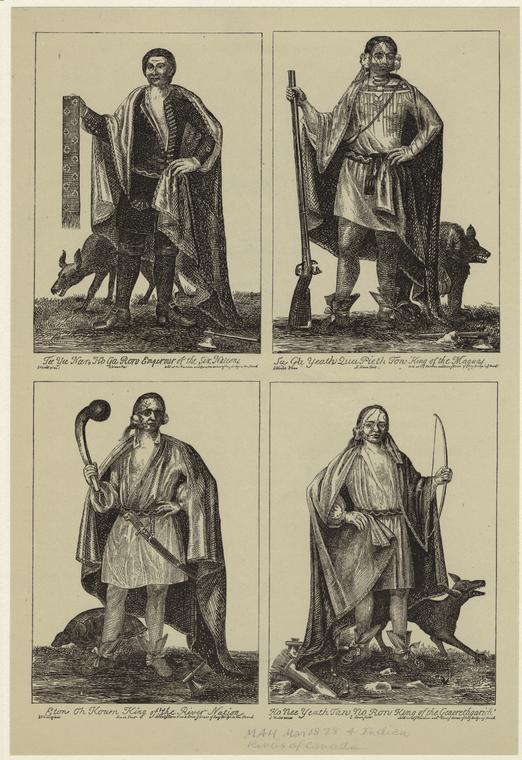

The most probable explanation for the name Mohock derives from a visit of four Iroquois chiefs, who met with Queen Anne in an audience in 1710. On April 22nd, the Post Boy wrote that they assured ‘her of their Readiness to assist the English in the Reduction of Canada, and over their Aversion against the French’.5 A few weeks later, the Tatler similarly reported about the ‘Emperor of the Mohocks and the other Three Kings’ at court.6 The state visit was sophisticated and highly publicized, yet prevailing attitudes towards ‘savagery’ and otherness could be gleaned as well, such as the following instance in the British Apollo of April 22nd 1710, where Englishmen were advised to get a London girl rather than ‘Some Indian – Pagans / Spoketh’ Language o’th’ Beast’.7 Likely it was this latter association between the Mohawk/Iroquois and a perceived barbarity of the Other which led to the subsequent naming of the phenomenon of fear in 1712, now known as the Mohock Scare.

On March 8th 1712, Swift wrote that this ‘race of Rakes, calld te Mohacks’ attacked D’avenant and ‘ran his Chair thro with a Sword’ (334). Multiple entries follow this assertion concerning the measures taken to ensure safe travel, debating whether one should go by foot, chair, or coach: ‘I forbear walking late, and they have put me to te Charge of some Shillings already […] I came home in a Chair for fear of te Mohocks’ (336). In spite of the general air of anxiety surrounding the Mohock issue in Swift’s Journal, he showed himself keenly aware of the influence exacted by the press, asserting on March 12th that ‘Grubstreet Papers about [the Mohocks] fly like Lightning’ (336). His belief that there may be ‘no Truth or very little in the whole Story’ (336) indicates that, excited by Grubstreet journalism, public imagination of the Mohocks far eclipsed actual events.

In the rumor-fueled perception of the public, the Mohocks were a stereotypically upper-class band of marauding rakes, anecdotally described as ‘Peers and Persons of Quality’,8 who caroused in the streets of London, assailing innocent passers-by at random between March and April of 1712. The Spectator called them a ‘nocturnal Fraternity’,9 whose leader was named the Emperor and carried engraved on his brow ‘a Turkish Crescent’. After imbibing copious amounts of alcohol, they would ‘make a general Sally, and attack all that are so unfortunate as to walk the Street’. Indeed, according to the Spectator, theirs was ‘an outragious Ambition of doing all possible Hurt to their Fellow-Creatures’, which ‘is the great Cement of their Assembly, and the only Qualification required in the Members’. Titles and offices were conferred upon members depending on their specific abilities. Some ‘are call’d the Dancing-Masters, and teach their Scholars to cut Capers by running Swords thro’ their legs’, others, named ‘Tumblers’, ‘commit certain Indecencies, or rather Barbarities’ upon women whom they had turned upside down, put into tar-filled barrels, and tumbled down a hill – an act that John Gay also referenced in his Trivia (1716): ‘How matrons, hoop’d within the hogshead’s womb / Were tumbled furious thence, the rolling tomb / O’er the stones thunders, bounds from side to side’.10 As will become clear shortly, there is little evidence that there existed an actual organization operating under the name Mohocks. Yet, in the broader context of eighteenth-century sociability, even a scare based on fundamentally unsociable behavior would unsurprisingly be imbricated in a club system, with all the attending attributes thereof such as titles and rituals, even if those are centered around debauchery and violence rather than manners and convivial sociable activity. Thus, the great anxiety of clubbable society in London appears to have been a perversion of their sociable ideals, a shadow of their club landscape, rather than mere violent chaos; and it is to this anxiety that the papers predominantly appealed, fermenting city-wide panic.

Broadsides were widely circulated, such as The Town Rakes; or, The Frolicks of the Mohocks or Hawkubites (1712) and A True List of the Names of the Mohocks (1712), the latter of which claiming to know precisely who had been arrested on account of being a Mohock (Statt 182). In a letter dated to March 14th, Lady Strafford compiled a list of additional Mohockish devilry, among them another reference to the tumblers: they ‘put an old woman into a hogshead, and rooled her down a hill, they cut of soms nosis, others hands, and severel barbarass tricks, without any provocation’.11 In this letter, she also identified Edward Montagu, the Viscount Hinchingbroke (1692 – 1722), as one of the Mohocks. While her account is second-hand at best, it will become apparent shortly that Hinchinbroke’s involvement in the Mohock Scare is based on factual evidence; and, being both grandson to John Wilmot, the 2nd Earl of Rochester (1647 – 1680), perhaps the most well-known Restoration rake, as well as father to John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich (1718 – 1792), a man of Hell-fire fame, his name does fit intriguingly into a legacy of rakery.

- 11. Thomas Wentworth, The Wentworth Papers 1705-1739, with a memoir and notes by James J. Cartwright (London: Wyman & Son’s, 1883), p. 277.

The Mohock episode did not only generate fear such as the one readily apparent in Swift’s or Lady Strafford’s writings, but captured the literary imagination as well. Aside from Trivia, John Gay’s first play, The Mohocks (1712), also made heavy use of the eponymous scare. Mirroring the details given in the Spectator of March 12th, The Mohocks depicts the initiation of a new member by the Emperor, providing him with the name Cannibal. After much singing – ‘Then a Mohock, a Mohock I’ll be / No Laws shall restrain / Our Libertine Reign / We’ll riot, drink on, and be free’12 – the illicit gathering attacks a group of guards, forcing them to switch clothing before accusing them of being Mohocks in front of a set of judges. Treating the topic in a similarly light manner, The Mohocks: A Poem in Miltonic Verse (1712), called them ‘Great Reformers, whose exalted Souls / Despise stiff formal Rules, and Knots of Law’,13 couching their exploits in mock-heroic tones. Tangentially related, one also finds Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock (1712-17), written during the scare. In this work, the Baron cuts off Belinda’s hair (albeit in much tamer fashion), similarly to the Mohocks, who allegedly did so to Mr. D’avenant, the scalping serving as a reference to the Mohock’s Iroquois namesake.14

- 12. John Gay, The Mohocks. A Tragi-Comical Farce (London: Bernard Lintott, 1712), p. 4.

- 13. The Mohocks: A Poem in Miltonic Verse. Address’d to the Spectator (London, 1712), p. 6.

- 14. Neil Guthrie, ‘”No Truth or very little in the whole Story”? A Reassessment of the Mohock Scare of 1712’, Eighteenth-Century Life (vol. 20, n° 2, 1996), p. 39.

Despite the preponderance of allusions and literary references to the Mohocks, and the wild rumors of organized asocial behavior, the question of their existence is far from settled. As a gang of rakes supposedly carousing in the streets of London, they fit into an enduring tradition such as the Tityre Tu, the Bugles, the Hectors, and the Damned Crew,15 and Calhoun Winton asserts that the Spectator sought to make use of such a sensationalist history to generate publicity for John Gay’s work.16 ‘Londoners,’ Winton claims, ‘were prepared to believe the rumor’ (20). Moreover, Erin Mackie argues that the three issues of the Spectator dealing with the topic – no. 324, 332, and 347 – used the Mohocks ‘in a generalized satiric offensive against late-night roistering and whoring’ in line with the paper’s overall reformative thrust.17 Another potential reason for the proliferation of frightful rumors is the tense political situation in 1712, and the propensity of both Whigs and Tories to use the press as a vehicle for their reciprocal criticisms. According to Statt, Tory accounts such as The Mohocks Revel (1712) or Plot upon Plot (1712) described the Mohocks ‘as a prelude to a Whig overthrow of the government’ (183). Such accusations were countered by the Whig publication The Observator on March 15th, which called out the ‘villainous Grubstreet Pamphleteers’ and claimed that the Mohocks took part in a Jacobite plot wherein they were the ‘Forlorn Hope of the French and the Pretender’s Faction’.18 On March 24th, The Medley also noted that the topic had become intensely politicized, drawing attention away from other serious issues, seeking instead ‘to keep the Mob honest’.19

- 15. Thornton Shirley Graves, ‘Some Pre-Mohock Clansmen’, Studies in Philology (vol. 20, no. 4, 1923), p. 421.

- 16. Calhoun Winton, John Gay and the London Theatre (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1993), p. 171.

- 17. Erin Skye Mackie, Rakes, Highwaymen, and Pirates. The Making of the Modern Gentleman in the Eighteenth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UVP, 2009), p. 57.

- 18. The Observator, March 15th, 1712.

- 19. The Medley, March 24th, 1712.

Despite there being little concrete evidence for the Mohocks having existed as a formalized club or gathering – already in 1756, William Maitland’s extensive History of London called the rumors surrounding the Mohocks ‘idle and fictitious Stories, artfully contrived to intimidate the People’20 – what can be inferred with more accuracy is a general trend of street violence in the early eighteenth century. Daniel Statt and Neil Guthrie have separately traced the to-and-fro between criminal activities and corresponding responses from the judges of the peace. Violent activity occurred predominantly in Holborn, Covent Garden, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and Red Lion Square, and on March 11th 1712, the Middlesex Justices commanded the watch to be doubled ‘in order to suppress nocturnal riots’ (Statt 185). In the night of the same day, an attack on the constable John Bouch led to the arrest of multiple assailants who were later released on bail, among them most notably Lord Hinchinbroke and one Sir Mark Cole. Their bails came to 1500 pounds and 900 pounds respectively, and the enormity of those sums likely fueled the rumors of marauding gangs of the elite creating disturbances in London (188). The shield granted by wealth becomes most apparent, however, when one considers that Hinchinbroke, ‘indicted for assault and riot as a Mohock in 1712, was a Member of the House of Commons in 1713’ (197). In any event, multiple other arrests were made, and quite a few gentlemen were accused of general Mohock-behavior as a result, but legal documents show these arrests to have been largely unrelated to one another, leaving little room for interpretations of organized criminal activity rather than spontaneous outbursts of violence (Guthrie 48).

- 20. William Maitland, The History of London. From its Foundation to the Present Time (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756), p. 510.

The Mohock phenomenon experienced a short-lived revival in the late eighteenth century, as a group of four men behaved riotously, drinking heavily and going about town roughing up whomever they saw. William Hickey described multiple altercations with this group, claiming that he had earned himself the moniker ‘The anti-Mohawk’ on account of his strident and loud opposition to their loutish behavior.21 Having emerged in 1771, this group of Mohocks came to an end in 1774, after they ‘overdid it and thus were brought before a judge’ (309). They scattered in the aftermath of their trials. Two went to America, one to Holland, and the last to Paris, marking at last the end of the Mohocks of the eighteenth century.

- 21. William Hickey, Memoirs of William Hickey, (1749-1775), ed. Alfred Spencer (London: Hurst & Blackett, 1919), vol. 1, p. 274.

Share

Further Reading

Graves, T. S., ‘Some Pre-Mohock Clansmen’, Studies in Philology (vol. 20, no 4, 1923), p. 395-421.

Guthrie, Neil, ‘”No Truth or very little in the whole Story”? A Reassessment of the Mohock Scare of 1712’, Eighteenth-Century Life (vol. 20, no 2, 1996), p. 33-56.

Mackie, Erin Skye, Rakes, Highwaymen, and Pirates. The Making of the Modern Gentleman in the Eighteenth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009).

Statt, Daniel, ‘The Case of the Mohocks: Rake Violence in Augustan London’, Social History (vol. 20, no 2, 1995), p. 179-199.

Winton, Calhoun, John Gay and the London Theatre (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1993).