Abstract

Periodicals or periodical publications play a major role in sociability. By their form, their numerous themes and articles, they act as sources for discussion and exchanges in different sociable places (coffee-houses, clubs, Salons). Because periodicals host very different voices and opinions, and tackle different sorts of subjects, they shape specific sociable practices. In fact, while endeavouring to reshape sociability in their pages, they finally create their own model, which can be seen as a virtual sociable space.

Keywords

A ‘periodical’ or periodical publication is a text published at regular intervals. The periodical is characterized by its lightness and therefore its mobility (it could also be called ‘leaves’), the variety of its subjects, the reduced size of the articles that comprise it, and an easier and wider dissemination than that of the books. The periodical form appeared at the end of the sixteenth century in Holland, England and France, and very quickly aroused the interest of society. The recurrence of the publication, which enables it both to provide a continuation for certain subjects and to offer brief forms which easily renew interest, makes it an appealing object for various social categories, nevertheless limited by the need to be educated and to be relatively well-off.

An object of sociability par excellence, the periodical can be shared, disseminated, taken, read in public and commented upon. By the diversity of its content, it creates the subjects of discussions and by their brevity, it prevents boredom. Games or puzzles are also part of the content that participate in practices of sociability.

Periodicals include reviews of books and performances, articles on political, cultural or social events, and excerpts from books and poems. In other words, texts are characterized by a formal and thematic diversity. All subjects are approached with some severe restrictions on religion and politics, although this concerns England less than France.1

This diversity encourages a wider audience, readers ranging from scholars to intellectuals, the bourgeoisie, the nobility, and the clergy as well. Various social environments are to be found or discovered through the means of the periodical. This textual form is thus not only used for itself, as a source of discussions for the moment of sociability that is announced, but it helps to transmit and promote practices of sociability, in circles of people who would be excluded. The periodical thus occupies a central role in the dissemination of sociable customs since it makes it possible to identify these practices and to make them known.

- 1. In his newspaper Le Pour et Contre, Prévost wrote : ‘[Les Ecrits Périodiques en Angleterre] ne sont pas plus anciens que la Guerre Civile. Les deux Partis, également intéressés à justifier leur conduite & leurs entreprises, par des relations favorables à leurs vues & par des réflexions conformes à leurs principes, faisaient imprimer régulièrement à Londres & à Oxford tout ce qu’ils jugeaient à propos de communiquer au Public […]‘, Prévost, Le Pour et Contre (t. 19, n° 280, 1740), p. 297. This citation shows that English periodicals had a political background and that they reflected and spread different opinions. Political matters were not banned by the government, a freedom of expression not to be found in Catholic France.

Since it is an object, it can be brought to various places; it can be lent or rented, depending on the circumstances. The periodical is usually a component of places of sociability. It is one of the few objects that is not specific to an environment of sociability or a certain social class. In the eighteenth century, it was present in salons, but also in cafés, which sometimes offered newspapers for reading, thus attracting a more regular clientele. It was also available for renting or reading in libraries, more or less private, often set up by booksellers. Finally, it occupied a prominent place in clubs, these typically English men's societies where they met to discuss current social and political events. In the latter two cases, the club or library entrance fee was used to finance several subscriptions to newspapers and magazines. The periodicity of periodicals could thus provide the reason for the next meeting.

The periodical therefore invests places of sociability but not only. In turn, it becomes a space of sociability, testifying to various practices that it re-orders to form a unique place, a virtual place of sociability. Indeed, periodicals were characterized by a diversity of voices, from the editors’ perspective and from the readers’ perspective: the editors of these texts were often multiple (mostly when the periodical had a short periodicity or if there were many pages) and they were not always easily identified: texts were not signed and different persons could participate in the writing of an issue depending on the subject. At the same time, periodicals presented readers' submissions, whether they were fictional or not, but which, whatever their origin, portrayed a plurality of voices and personalities. According to this perspective, the periodical takes the form of a collection combining themes and characters who may not meet, either for reasons linked to social conditions or due to geographical distance. When it has a totalizing ambition, the periodical succeeds in bringing together readers from very different professional or social backgrounds. An issue could thus tackle women's fashion, then methods of inoculation of smallpox, and then proceed to a detailed and scholarly reflection on a particular linguistic phenomenon while integrating various poems, songs, or word plays. In this sense, the periodical creates a virtual space in which can be expressed different practices of sociability.

There are several forms of periodical. The term ‘periodic’ refers to very different realities depending on the newspaper and its intention. Some were published on a regular basis, have a recurring structure from one number to another, while others struggled to follow a certain norm of publication or form. Some of them focused on specific subjects that could partially restrict their audience, especially when they specialized in medicine or were used to defend a political or religious point of view.2 Others were more open and had a broad cultural content. These periodicals, in particular, may have been at the origin of a new virtual form of sociability.

- 2. Many newspapers were used to spread specific ideas and opinions. In France, the Journal de Trévoux (1701-1767), for instance, was a newspaper supporting Jesuit thought. In England, The Examiner, edited by Jonathan Swift (1710-1714), promoted the Tory viewpoint against Whig ministers.

Two scholarly theories are available on the origins of periodicals: journalism is traced back before printing, assuming that only the regularity counts, even if the document was handwritten; or it is assumed that journalism was born with the printing press.3 Indeed, it should be remembered that printed periodicals developed almost simultaneously in France, England and Holland at the end of the sixteenth century and at the beginning of the seventeenth century, under the influence of religious controversy. The desire to win the support of the public turned print into a propaganda instrument, and the large books thus gave way to small treatises, which were easier to disseminate. The format was then reduced and the number of subjects increased. The custom was to sell the stories of remarkable events at low prices to attract a large public.

- 3. It would be a bit of a caricature to classify scholars in those two categories. Actually it depends on the selected viewpoint. François Moureau, for example, defends the idea of handwritten newspapers but he also agrees that the rise of the printing press was a turning point in the story of journalism.

In England, the first periodicals appeared very early, at the end of the reign of Elizabeth and the beginning of that of James I (in the 1600s). There were a large number of flying leaves called ‘news’, which contained the account of various events, British or European. In 1622, the first periodical was published by Nicholas Bourne and Thomas Archer with The Weekly News, which was supposed to inform about current events in various European countries. It was essentially a translation of a Dutch leaf. In 1702 the first European daily was published in England, under the direction of the bookseller Elizabeth Mallet. Entitled The Daily Courant, the one-page periodical contained a dozen translated articles from foreign newspapers. The newspaper doubled its volume when it was bought by the printer Samuel Buckley.

Throughout the seventeenth century, periodicals were structured; they singled out their Dutch model and diversified topics. Unlike France, the birthplace of literary periodicals also called ‘magazines‘, England and Holland had a more political press. Although cultural subjects were tackled, the political dimension was rarely absent. During the reign of Queen Anne, periodicals multiplied, notably by crystallizing around two parties, the Tories and the Whigs, who disputed power in Parliament but also by mobilizing public opinion through the press.

Daniel Defoe, a great pamphleteer in addition to being a famous novelist, was one of the first to authorize polemical discourse in his periodical, The Review (1704-1713). Many men of letters, such as Bolingbroke or Jonathan Swift, collaborated to the periodical by sending texts and works. The Defoe periodical was first printed on a quarto sheet, once a week and sold a penny. Soon, as the periodicity and number of articles increased, the newspaper was sold for two pence. The plan of the periodical was very simple and skipped without transition from satire to an examination of political measures, including reflections on the duel or the drunkard for example.

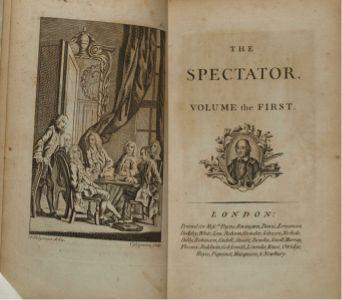

Defoe appeared in his periodical as the secretary of a club, the ‘Scandal Club‘, supposed to judge the wrongs and abuses of very different situations, sometimes linked to the relationship between two spouses, sometimes linked to questionable social practices. This practice was soon resumed by various periodicals, notably those relating to the vogue of the Spectators, of which The Spectator of Addison and Steele remains one of the models of the genre.4 The first periodical of this type was The Tatler (April 1709-December 1710), published by Steele with the help of Swift. Published three times a week, its success was immediate, to such a point that Steele was forced to have the previous issues reprinted in volume at the end of each quarter. To develop his project, Steele launched, with the help of Addison, a daily periodical, The Spectator (1711-1714), which quickly became a success throughout Europe. Some issues sold up to 20,000 copies and very quickly; two editions of duodecimo and octavo were introduced, and quickly out of print. Usually, each issue sold about 3,000 copies, which was already extraordinary at the time. The price fluctuated between a penny and two pence. Like Defoe's, the periodical is organized around a dramatization of the editors.

- 4. A periodical, more literary than political, but in which the morals, philosophy or painting of society had a prominent place. It initiated a periodic form that transcended many borders and had many descendants in Europe. Alexis Lévrier, in the printed version of his PhD, Les journaux de Marivaux et le monde des ‘spectateurs‘, highlights the influence of the periodical form in France and in Europe as well.

British periodicals were at the heart of a real struggle for power and political strength.5 A struggle for power first, because they allowed the dissemination of ideas and therefore the emergence of a public opinion; and secondly, a political struggle since Parliament was constantly creating new taxes (stamps for publication) or new constraints to limit the number of periodicals and their speeches. However, the tone remained more liberal in England, insofar as it was possible to discuss politics, unlike in France for example. However, the tax burden on periodicals increased the cost of sales per number, reducing the number of potential readers. It was also this high cost of purchase that led to the establishment of common reading places, to share these periodicals. Progressively, the periodicals were divided into two categories, newspapers more closely linked to political news on the one hand and magazines endowed with cultural and literary content on the other hand. Periodicity accompanied this distinction, since newspapers kept a frequent, daily or weekly distribution, while cultural newspapers relied on a monthly format.

- 5. For more information on the political role of the press see Bob Harris’s book, Politics and the Rise of the Press: Britain and France, 1620-1800 (Abingdon: Routledge, 1996). The major work of Jürgen Habermas, L'espace public: archéologie de la publicité comme dimension constitutive de la société bourgeoise (Paris: Payot, 1978) has highlighted the importance of journalism in the constitution of a new political sphere, called ‘bourgeoisie’.

The periodical offered articles for a large part of the wealthy class of the population but it also gave a significant place to women in its pages. In this sense, it contributed to the progressive emancipation of women, notably by giving them easier access to knowledge and news of the world, such as political decisions, civic rights, international conflicts or cultural discoveries.6 Moreover, it published several texts written by women (or presented as such) which reinforced the impression of diversity. In The Tatler, for example, the female audience was specifically summoned and mentioned as a public of the periodical.

It is therefore appropriate, without exaggerating, to emphasize the democratic role of the periodical both in its wide dissemination and in its variety of themes and textual forms represented. These two characteristics are naturally linked to the need to sell as many issues as possible.

- 6. Boulard, Claire, Presse et socialisation féminine en Angleterre de 1690 à 1750 : Conversations à l’heure du thé (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2000). Claire Boulard explains that the printing press contributed to develop female sociability as well as to facilitate women taking their place in the world.

Share

Further Reading

Barker, Hannah, Burrows, Simon (eds.), Press, Politics and the Public Sphere in Europe and North America, 1760-1820 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Black, Jeremy, The English Press, 1621-1861 (Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 2001).

Bony, Alain, Joseph Addison, Richard Steele: ‘The Spectator‘ et l’essai périodique (Paris: Didier Erudition-CNED, 1999).

Dumouchel, Suzanne, Le journal littéraire en France au dix-huitième siècle: Emergence d'une culture virtuelle (Oxford: Oxford University Studies, 2016).

Haywood, Eliza, ‘Women writers in English 1350-1850‘, in Patricia Meyer Spacks (ed.), Selection from the female spectator (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Levrier, Alexis, Les journaux de Marivaux et le monde des ‘spectateurs‘ (Paris: PU Paris Sorbonne, 2007).

Moureau François, La plume et le plomb. Espaces de l’imprimé et du manuscrit au siècle des Lumières (Paris: PU Paris Sorbonne, 2006).

Stuncke, Marie-Christine (éd.), Media and political culture in the eighteenth century (Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie Och Antikvitets Akademien, 2005).