Abstract

Pleasure-driving emerged as a new elite sociable pastime in late eighteenth-century Britain. The best and most desired pleasure-carriage was the phaeton. Toweringly high and extremely dangerous to drive, the phaeton was the supercar of the eighteenth century. Men and women alike imbued the phaeton with meaning as a sociable practice and how one drove one’s phaeton was an indicator to others of your character.

British carriage ownership rapidly increased over the course of the long eighteenth century and by its close, elite Britons began to enjoy the sociable pastime of pleasuring/pleasure driving: that is, carriage travel for the purposes of leisure and sociability, to be seen and to meet others out in the streets driving rather than the practical need for transportation. A host of new carriage models emerged in the middle of the eighteenth century to facilitate this new pastime. Some earlier models evolved into new, adapted forms and hung on new types of coach springs. The shallow body and fold-down hood of the two-person calash gave way to the four-seat vis-à-vis arrangements of landaus, landaulets, and barouches at the end of the eighteenth century. The two-wheeled chaise or chair – although still popular– evolved into other forms such as the curricle, gig, whiskey, and the four-wheel phaeton. Improvements in steel production enabled the production of longer coach springs, the increased imitation of continental coach models in Britain and their subsequent innovation, and even new road infrastructure and legislation such as the Turnpike Act provided the perfect conditions for pleasure-driving to take off as an elite leisure activity.

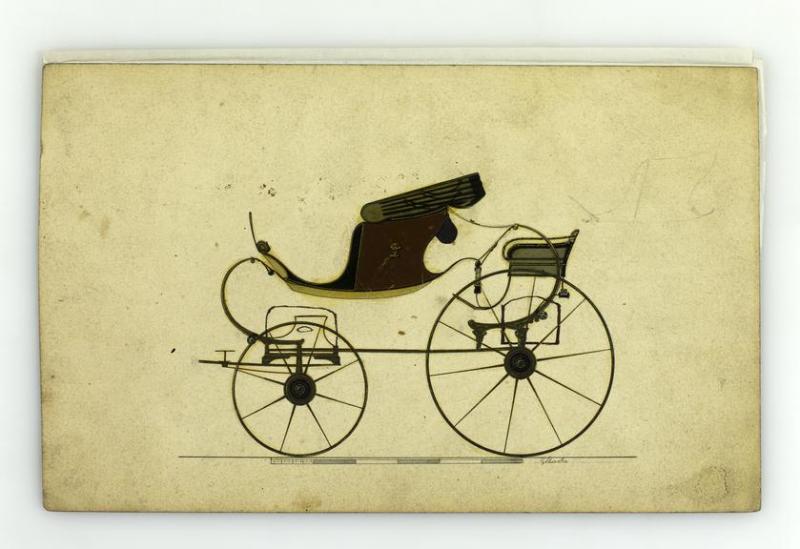

Phaetons were one- or two-person carriages with an open-top, open-sided lightweight body that sat atop four wheels, with two larger wheels at the back and two smaller wheels at the front. Some had detachable hoods, usually made from leather, while others had none to keep the carriage as lightweight as possible – this enabled them to travel very quickly. The phaeton body was usually hung high above the wheels on long-tailed high ‘phaeton’ coach springs specifically designed to support the carriage body and prevent the owner from falling out the open sides. It was an owner-driven vehicle without a coachman, and often without postillions, and was usually pulled by two horses or ponies.

The open top meant that the phaeton could only be driven in fair weather and the springs were not sturdy enough to travel for long distances. The cost for the body of a phaeton, without the wheels, axletree, upholstery, or paint, would begin at £20 but the finished product could easily cost upwards of £100. This cost was prohibitively expensive for even many wealthy people to have a carriage designed solely for pleasure driving.1

- 1. William Felton, A Treatise on Carriages (London: Printed for and Sold by J. Debrett, 1794), p. 85.

The purchasing and maintaining of a suitably glamorous collection of carriages for town and country roads, for domestic and continental travel, and for promenading and pleasure-driving formed a significant component of elite families’ domestic expenditure – often the expense required to maintain a bevy of carriages and horses was costlier than the carriages themselves. Truly only comparable to homes and dress, carriages were a unique and overt display of elite status – but a pleasure carriage set those of highest rank and fortune apart from middling coach owners.2

- 2. Ben Jackson, ‘To Make a Figure in the World: Identity and Materiality Literacy in the 1770s Coach Consumption of British Ambassador, Lord Grantham’, Gender & History (2022), p. 1-22, here p. 9. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12655

The phaeton afforded intimate sociability between two occupants as driver and passenger. The phaeton emerged, in part, to facilitate new forms of elite sociability; its long, bendy springs, its open sides, and its ability to travel at significant speeds enabled drivers to conspicuously display their control, daring, and skill. It was a carriage designed for performance and spectacle. This carriage model enabled people to perform their elite status to others and encouraged others to assess your ‘driving’. The control of your own body, emotions, vehicle, and horses would reveal to onlookers the sort of driver, or person, you were. From the novels of Frances Burney to Jane Austen to the satirical cartoons of Gillray and Cruikshank and the essays of Thomas de Quincey there was a significant cultural investment in the meanings behind driving as a new eighteenth-century sociable practice. In a polite, sociable society in which the social choreographies of the fan, snuffbox, punchbowl, and tea table, to name a few, were bound up in non-verbal communication of who you were, or aspired to be, driving oneself became a new social performance. For example, in Frances Burney’s 1778 novel Evelina, Lord Orville’s slow and careful phaeton driving is a performance of his restrained, manly gentility whereas the foppish Mr Lovel and the rakish Lord Merton’s reckless phaeton driving reveals their lack of gentlemanly qualities to both the onlookers in the novel and its readers.3 In 1801, Jane Austen found her suitor John Evelyn’s phaeton pulled by four horses ‘very bewitching’ and had in her ‘frailty […] a great desire to go out in’ of it. His driving made her think him ‘very harmless’.4 For both Evelina and Austen, the assessing male phaeton-drivers was part of the courtship process.

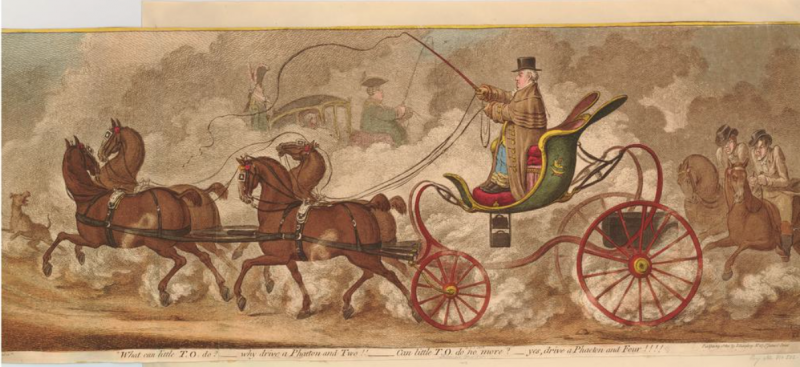

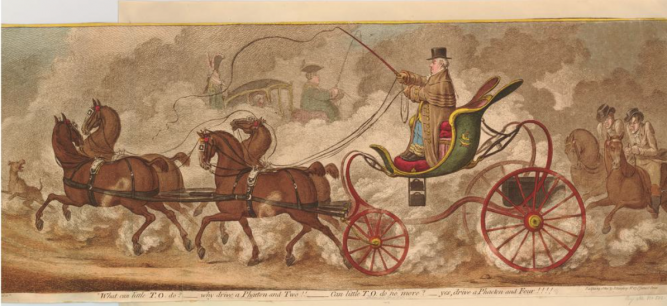

The phaeton was bound up in gender difference. For example, men and women had different phaetons designed for different forms of gendered sociability. While phaetons were almost always owned and driven by men, ‘lady’s phaeton’ were carriages hung closer to the wheels on shorter springs for both safety of the occupant and for ease of entering the vehicle elegantly, and were often pulled by ponies rather than horses. For example, compare the height and mechanical intricacy of the male-driven high Phaeton in ‘Figure 1’ with the female driven low phaeton almost hidden in the trees in George Stubb’s The Milbanke and Melbourne Families c.1769.

The male phaeton driver performs to others his bravery and daring, skill and agility and the female phaeton driver displays her fine clothes. Austen, in Pride and Prejudice (1813), gave the sickly Anne de Bourgh a ‘little phaeton and ponies’ to drive around Rosings Park and its environs that enabled her to perform polite, condescending feminine sociability to Charlotte Collins and her guests.5 In his series of essays The English Mail-Coach (1849), Thomas de Quincey was transported by the developments in carriage design in which the phaeton was a small part. Mail-coaches’ extreme speed, ‘grandeur and power’ provoked a visceral fascination in de Quincey’s mind and ‘had so large a share in developing the anarchies of [his] subsequent dreams; an agency which they accomplished, 1st, through velocity, at a that time unprecedented – for they revealed the glory of motion.’6 As a young man in Oxford, the thrill and danger of riding on the outside seats of the English Mail-Coach fascinated de Quincey with their potential for sudden death.

In fashionable, urban centres owner-driven pleasure carriages were key parts of elite leisure. The route du roi or ‘Rotten Row’, the most famous carriage promenade in London, ran along the south side of Hyde Park. After Charles I opened the park to public in the 1630s, he used the route to parade along in his royal carriage from Kensington to St. James’s Palace.7 By the eighteenth century, London’s beau monde paraded along this lit track dressed in their best clothes, riding in their ornate carriages, and meeting one another out in their carriages and speaking to passers-by. At the opening of parliament, the formal procession of ambassadors, and royal birthdays, huge crowds would assemble to see the parade of aristocratic coaches into St. James’s Palace. The invention of new types of owner-driven carriage such as the phaeton disrupted this elite sociable pastime. These new carriage types placed a greater importance on how one drove one’s carriage rather than the finery of it and its occupants. This was matched by its simpler ornamentation than the ostentatious carriages of the earlier part of the eighteenth century. In fact, a certain type of phaeton emerged in the 1790s, the ‘sociable phaeton’ which had additional seats to carry more passengers. In his influential A Treatise on Carriages (1794), William Felton wrote ‘a sociable is a phaeton with a double or treble body, and is so called from the number of persons it is meant to carry at one time. They are intended for the pleasure of gentlemen to use in parks, or on little excursions with their families’ (Felton 87).

- 7. Liza Picard, Restoration London (London: Phoenix Press, 1997), p. 60–61.

Portly Onslow, wearing a coachman’s long overcoat and sitting upright in a high-perch four-horse phaeton, cracks his whip unperturbed by the dog jumping up and startling his horses. That Onslow is depicted in a coachman’s coat reflects elite men’s rejection, in the later eighteenth century, of magnificent dress for plainer, simpler clothes.8 Onslow, lacking the full equipage of coachmen and grooms, blurs the distinction between master and servant, elite and non-elite. Gillray’s comment is that despite Onslow’s obvious skill in driving four-in-hand such an obsession with horses and phaetons did not befit a grown gentleman; the dust caused from the commotion of the horses and phaeton obscures the elaborate coach in the background of the print that was all part of the spectacle and performance of the carriage promenade on the Rotten Row. Therefore, the phaeton both enabled new forms of elite sociability but also reveals some of the contradiction of the carriage promenade and performance.

Gentleman phaeton-drivers formed part of the eighteenth century’s associational world of clubs and societies. Driving clubs such as the Bensington Driving Club and the Four-in-Hand Club emerged in the early nineteenth century in which adopting a specific type of coach marked out the difference between clubs and were integral to clubs’ collective, associational identity. The Barouche Club were seriously invested in the structural and aesthetic design of their club carriages and issued a notice in the Sporting Magazine in February 1809 which gave explicit instructions for a host of meticulous material specifications for the club’s carriages’ model, design, mechanical and structural elements.

The phaeton was designed for and used within the new sociable practice of pleasure-driving. Its high-springs and towering height imbued it with significant cultural meaning that enabled drivers, passengers, and spectators to make judgements about the character of ‘phaeton-drivers’

- 8. David Kuchta, The Three-Piece Suit and Modern Masculinity: England, 1550–1850 (Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 2002).

Share

Further Reading

Crone-Romanovski, Mary, ‘The Matter of the Carriage in Frances Burney's Evelina’, Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture (vol. 49, 2020), p. 159-176.

Donnelly, Bridget, ‘Accidents, Risk Management, and Driving Culture, 1780–1830’ Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture, (vol. 49, 2020), p. 177-199.

Ford, John, Coachmaker: The Life and Times of Philip Godsal, 1747–1826 (Stroud: Quiller, 2005).