Abstract

The Royal Academy of Arts, founded in 1768, was an example of restricted professional and cultural sociability. The statutes limited the number of members and imposed rules of good behaviour to ensure that politeness prevailed within the institution. Social connections, exclusively between artists and aristocratic amateurs, were forged during the annual banquet. The exhibition held at Somerset House from 1780 was the means to create a public, who, with the exception of the lower classes, excluded by an entrance fee, could share in the experience of visual sociability. At the end of the century, because of its inner conflicts, the Academy was criticized for its anti-sociability.

The Royal Academy of Arts, was founded in 1768. It had been preceded by associations of painters whose main aim was to provide drawing sessions with a model, such as St Martin’s Lane Academy under the management of Hogarth in 1734, or to organize exhibitions as the Society of Artists of Great Britain did at Spring Gardens at the beginning of the 1760s. The royal charter the Academy was granted and the statutes it set for itself inaugurated a new era for artistic sociability by giving it an institutional basis. As a social body the Academy shared characteristics of previously founded foreign academies and of the nascent British clubs, some of which, such as the Rose and Crown or the Society of Virtuosi of Saint Luke, at the turn of the century, were artists’ clubs.

Membership, like that of clubs or of the French Académie, was strictly defined and sociability limited: the number of Academicians was set at 40, which might have been an adequate figure to maintain a network of friendship.1 Besides, their origin was defined: membership was restricted to professional artists and they could not belong to ‘any other society of artists established in London’.2 This also meant that connoisseurs were excluded, which was not the case in the French Académie where ‘amateurs honoraires’ were accepted. These two conditions reflected the previous conflicts of painters with the Society of Dilettanti and their diffidence towards amateurs as well as the antagonism within the ranks of artists themselves. The statutes did not exclude female members though: two women, Angelica Kauffmann and Mary Moser were among the founding members and had voting rights, unlike the female members of the Incorporated Society of Artists.3 However they were the only two female Academicians in the eighteenth century. Artists of foreign origin were also accepted provided they resided in Great Britain. There was also the possibility for Italian or French academicians to draw at the Royal academy and attend the lectures.4 A new category was created in 1769, that of ‘Associate Members’, limited to twenty, without any share in the decisions and administration of the institution. From that year on there were also honorary members, many of whom were admitted in a teaching capacity. The Royal Academy was thus defined as a strictly professional organization. The hierarchical distinctions between various categories of members, despite equality of merit, and the powers given to the Council, conducting academic affairs, showed that its internal structuring was inspired by the French academic model rather than by the egalitarian principle that prevailed in some clubs or in Hogarth’s Academy.5

- 1. See Daniel Roche, Les Républicains des Lettres (Paris, Fayard, 1988), p. 165.

- 2. The Instrument of Foundation [1768], in Sydney C. Hutchison, The History of the Royal Academy 1768-1986 (London, Robert Royce Ltd, 1986), p. 245.

- 3. See William T. Whitley, Artists and their Friends in England 1700-1799, vol.1 [1928] (2nd ed., New York and London: Benjamin Blom, 1968), p. 238-239.

- 4. Abstract of the Instrument of Institution and Laws of the Royal Academy (London: J. Cooper, 1797), p. 24.

- 5. See Ian Pear, The Discovery of Painting (New Haven: Yale UP, 1988), p. 124.

In keeping with the notion of the painter as a gentleman as formulated by Jonathan Richardson and Joshua Reynolds (the Royal Academy’s first president), politeness was another aspect of sociability that was considered in the statutes of the Academy: Academicians were supposed to be endowed with ‘fair moral characters’ and the General Assembly was given the right to expel any ‘obnoxious’ member (Hutchison 245). Students, selected on artistic ability (there were seventy-seven of them, mostly painters, in the first year of the institution), were also expected to respect social rules of good behaviour and the Council could act as a disciplinary body if necessary, both for Academicians and pupils. Provisions were made in the statutes against unruliness, such as introducing strangers without permission or damaging the casts, which were teaching material (Hutchison 29-30). The preoccupation with civilized comportment also appears in the creation of a ‘keeper’, elected among Academicians to preserve ‘order and decorum’ among the students (Hutchison 247).

Good behaviour was indeed a prerequisite of cultural sociability and so was dining. Having supper together was already a characteristic of social life at artists’ clubs in the first half of the century and remained so in artists’ associations in the 1760s. After their first meeting, on January 2nd 1769, thirty Academicians dined at St Alban’s Tavern with a few members of the aristocracy, invited as connoisseurs and patrons of the art. The following year the Academy held its annual dinner in its own rooms, the gallery in Pall Mall. Thus was initiated the tradition of the banquet on academic premises. From the start, it was an opportunity to open the institution, even though briefly, to the aristocratic amateurs that were excluded in the statutes. The annual banquets mixed features of the Foundling Hospital ritual (dining on the premises amidst works of art) and of the dinners organized by the Society of Artists (dining on a specific day). From 1780 onwards, the Academicians and their guests met in the ‘Great Room’, the main exhibition room at Somerset House, usually on Saint George’s Day, April 23 (a date which had been set in 1771), just before the opening of the exhibition and after a private preview for the royal family, thus combining two forms of restricted sociability. Fine food and elegant entertainment were provided and the arrangement of tables encouraged the social mixing of artists and their potential patrons.6 At the end of the century the Academy’s banquet polarized public interest: it acquired a stronger political significance as a show of support for royalty while becoming a frequent butt of radical satire as in the writings of John Williams (alias Anthony Pasquin) or John Wolcot (alias Peter Pindar).7

- 6. Holger Hoock, The King’s Artists: the Royal Academy of Arts and the Politics of British Culture 1760-1840 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003), p. 219.

- 7. Anthony Pasquin, A Critical Guide to the Exhibition of the Royal Academy, for 1796 (London: H.D. Symonds, 1796); Peter Pindar, Lyric Odes for the Year 1783 (London: G. Kearsley, 1783).

Exhibitions had been a means for artists to seek wider recognition since the middle of the century. The Foundling Hospital held an all-year-round exhibition from 1739 onwards and the Society of Artists began to rent rooms in 1760 with the explicit purpose of showing British art. The exhibition on the premises of the academy, which originally lasted one month but was later extended to a period of six weeks, was an opportunity to promote a more open form of sociability, which concerned both the artistic professions and the emerging public for art. Inclusiveness was supposed to characterize the exhibition since it was meant to show the works of ‘all Artists of distinguished merit’ and not just Academicians (Hutchison 248). Exhibiting art also involved defining its potential public. Theoretically the civilizing function of art, pointed out by philosophers like Shaftesbury or Hume, seemed to entail the participation of the greatest number. In reality fear of public disorder had led organizers of the first artistic shows before the founding of the Royal Academy to try to exclude the lower classes, a precedent which was taken up in academic practice.8 For its first exhibition in Pall Mall in April 1769, the Royal Academy of Arts charged one shilling for admission to avoid the room being filled with ‘improper persons’.9

- 8. The fact of charging the public, for admission or for the purchase of a catalogue, was a bone of contention among organizers. See Brandon Taylor, Art for the Nation: Exhibitions and the London Public 1747-2001 (New Brunswick (NJ) : Rutgers UP, 1999), p. 11 sq.

- 9. Advertisement in the Exhibition of the Royal Academy MDCCLXIX, THE FIRST (London: n.p., 1769), in David H. Solkin (ed.), Art on the Line: the Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House 1780-1836 (New Haven, Yale UP, 2001), p. 40.

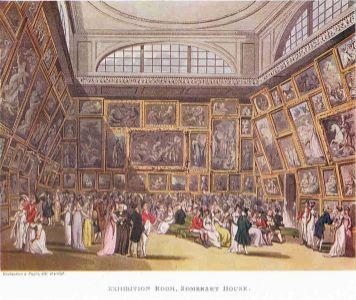

For those allowed in, the exhibition rooms were a place for social distinction and/or social intercourse. Some viewers were there only to be seen and acknowledge members of their own class or ‘only for the sake of saying they have been there’.10 However, ‘visual sociability’ could be achieved through the sharing of aesthetic emotions. The many engravings devoted to the Great Room at Somerset House, in themselves a sign of interest for the exhibition room as public space, show spectators in pairs and larger groups, thus suggesting that the viewing of art was a sociable experience, works of art being a source of comment and conversation.11 Even if the motto inscribed in the Great Room, ‘Let No Stranger to the Muses Enter’, seemed to incite spectators to behave like connoisseurs and comment on historical painting, the elite genre at the top of the academic hierarchy of painting, many among the people who attended were more interested in identifying the sitters in portraits. Yet sight-based sociability was hampered by mediocre viewing conditions due to the great number of pictures on display and the crowds drawn to the Great Room.12

- 10. Robert Baker, Observations on the Pictures now in Exhibition at the Royal Academy, Spring Gardens and Mr Christie’s (London: John Bell, 1771), p. 21.

- 11. See Stéphane Lojkine, ‘Le commerce de la peinture dans les Salons de Diderot’, in Jessica L. Fripp, Amandine Gorse, Nathalie Manceau and Nina Struckmeyer (eds), Artistes, savants et amateurs : art et sociabilité au XVIIIe siècle (1715-1815) (Paris: Mare et Martin, 2016), p. 187.

- 12. In 1780 there was an average of 2000 viewers a day. See Art on the Line, p. 37.

The limits of sociability at the Academy also appear in the works of Robert Strange and Anthony Pasquin, who make abundant use of the words ‘cabal’ or ‘junto’ to condemn factions of artists.13 For James Barry the root of anti-sociability lies in the undemocratic Council, in the structure of the institution proper.14 The ‘Bonomi affair’ in 1790 is an example of dissent, of the rampant xenophobia that made itself felt in the last decade of the century within the academy and led to the resignation of the president, Sir Joshua Reynolds: in his ‘Apologia’ the painter ascribed the rejection by the general assembly of his candidate, Italian-born Bonomi, for the post of Professor of Perspective, to increasing hostility to foreign talent within the ranks of Academicians, people ‘little versed in the little requisites of civil intercourse’.15

- 13. Robert Strange, An Inquiry into the Rise and Establishment of the Royal Academy of Arts (London: E. and C. Dilly, 1775), p. 98; Anthony Pasquin, A Critical Guide to the Present Exhibition at the Royal Academy, for 1797 (London: H.D. Symonds, 1797), p. 10.

- 14. James Barry, A Letter to the Dilettanti Society (2nd ed., London: J. Walker, 1798), p. 276-277.

- 15. Joshua Reynolds, ‘Apologia’, in The Literary Career of Sir Joshua Reynolds, ed. Frederick Whiley Hilles (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1936), p. 274.

Both in its statutes, barring connoisseurs from membership, and in its exhibitions, forbidding access to the lower ranks of the public, the Royal Academy of Arts opted for a restricted form of sociability in which exclusion meant control of who could have access to the artists or view the liberal arts. Besides, even though royal patronage of the Academy was supposed to unify a body of artists into a coherent whole, rivalries remained an obstacle to the full accomplishment of professional sociability, thus threatening theoretical attempts to promote the notion of the painter as a gentleman.

Share

Further Reading

Daniel Roche, Les Républicains des Lettres (Paris: Fayard, 1988).

Sydney C. Hutchison, The History of the Royal Academy 1768-1986 (London: Robert Royce Ltd, 1986).