Abstract

Eighteenth-century retail underwent major developments: growing numbers of shops with increasing specialization and a wider range of goods available to individuals, who were keen to buy and consume British products as well as goods from outside Europe such as textiles and china. As urban shopping areas developed, a ‘shopping culture’, as Helen Berry phrased it, emerged, which was ‘polite’ as well as sociable. Shopping often went beyond the acquisition of necessities and was frequently practiced as a leisure activity.

Growing Towns and Shopping Streets

Sociable shopping developed because in London as well as in spa towns such as Bath and in other smaller urban centres, genuine shopping streets, often with more expensive kinds of retail venues, sprang up, becoming part of the urban ‘leisure infrastructure’,1 which per se invited sociable interaction. One factor for this increase in venues is the corresponding growth of towns and cities.2 If, according to Maxine Berg, the number of ‘urban middling people’3 was 170,000 at the beginning of the eighteenth century, it more than doubled over the next 100 years. Attracting customers, shopping venues and shopping streets in particular were important for the local economy and served as spaces of sociable encounters. The Swiss traveller César de Saussure, who stayed in London in the 1720s and again a decade later, named four major shopping streets: the Strand, Fleet Street, Cheapside, and Cornhill:4 'Every house possesses one or two shops where the choicest merchandise from the four quarters of the globe is exposed to the sight of the passers-by’ (de Saussure 81). Later in the century, Oxford Street with its street lighting fascinated shoppers such as the German traveller Sophie von La Roche, who described a sociable nocturnal walk in 1786: 'We strolled up and down lovely Oxford Street this evening, for some goods look more attractive by artificial light [...] First one passes a watchmaker’s, then a silk or fan store, now a silversmith’s, a china or glass shop.'5

Of course, retail shops had existed prior to the eighteenth century, at a time when the classic village shop and open markets had played a major role for the purchasing of food and other necessities. It is obvious that pre-1700 shopping must have been conducive to sociable exchange, too.6 Yet the new fashionable urban shopping differs from earlier purchasing activities. It was often undertaken by women of the middle and upper classes, the rich and the nouveau riches, who participated in the virtual space of a 'social sphere' situated between the Habermasian public sphere and the private sphere.7 This new fashionable shopping had its routines, which were tied to the spaces where it occurred. In Chester, a North-Western provincial hub with urban features (Stobart 12-13), shops concentrated in the centre so that the city's inns, assemblies, and opportunities for walks provided the backdrop to wealthy customers' shopping, in the course of which leisure and the acquisition of goods became joint experiences. Bath, the fashionable spa town, made itself attractive to residents and visitors through offering numerous services and entertainments in its centre: e.g., taking the waters, visiting the assembly rooms, and also shopping. Luxury goods were exhibited and sold at high prices.8 Beyond the spatial unit of the street, shopping areas began to develop. Varying streets hosted luxurious shops in the course of the eighteenth century, particularly those close to the famous assembly rooms, which were magnets for shop-owners and customers (Cossic 113). Milsom Street and Bond Street in particular became brand names for pleasurable shopping. Individuals went out, often with family members or friends, not to purchase necessities but rather to look at and acquire fashionable luxury goods and to socialize while shopping. Due to the customers' elevated social status, fashionable shopping is much better documented than the purchasing of necessities prior to the long eighteenth century. Among the sources are articles in journals, which reacted satirically, articles reflecting on the morals of shopping while questioning the necessity of luxury goods, inventories, illustrated trade cards, and prints. In the newly emerging genre of the novel, episodes occasionally involved shops, like the glove shop in Samuel Richardson's Clarissa (Kowaleski-Wallace 89-91).

- 1. Jon Stobart, ‘Shopping streets as social space: leisure, consumerism and improvement in an eighteenth-century county town’, Urban History (vol. 25, n° 1, 1998), p. 3-21, see p. 4. Stobart's focus is on Chester.

- 2. Ian Mitchell, Tradition and Innovation in English Retailing, 1700 to 1850: Narratives of Consumption (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), p. 5.

- 3. Maxine Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, [2005] 2007), p. 211.

- 4. For the reference to Saussure see Helen Berry, ‘Polite Consumption: Shopping in Eighteenth-Century England’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (vol. 12, 2002), p. 382. César de Saussure, A Foreign View of England in the Reigns of George I. & George II. The Letters of Monsieur César de Saussure to His Family, transl. and ed. Madame van Muyden (London: Murray, 1902), p. 80.

- 5. Sophie von La Roche, Sophie in London 1786, Being a Diary of Sophie v. La Roche, trans. and intro. Clare Williams (Jonathan Cape: London & Toronto, 1933), p. 141.

- 6. On village shops see Mitchell, p. 77-80, and Hoh-Cheung Mui and Lorna H. Mui, Shops and Shopkeeping in Eighteenth-Century England (Kingston & Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press; London: Routledge, 1989).

- 7. Dallett Hemphill, C., Bowing to Necessities: A History of Manners in America, 1620–1860 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). On shopping and the public see Elizabeth Kowaleski-Wallace, Consuming Subjects: Women, Shopping, and Business in the Eighteenth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), p. 81, p. 120, p. 136.

- 8. Annick Cossic, Bath au XVIIIe siècle. Les fastes d'une cité palladienne (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2000), p. 112.

The Shops

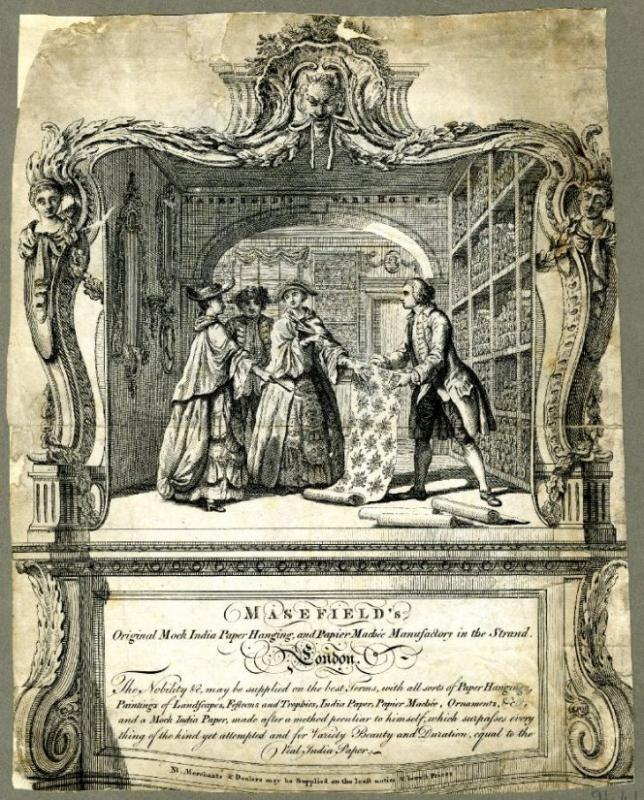

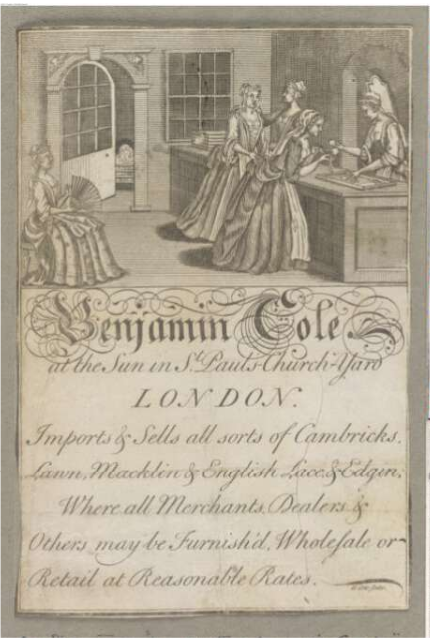

Historians of the department store, an institution that developed in the second half of the nineteenth century, have occasionally claimed that several of its features – among them shop windows to attract customers’ attention, and fixed prices - were novelties.9 These, however, can be found in eighteenth-century shops as well, where architecture facilitated interaction (Walsh 158-159). What did the shops look like on the outside to entice buyers? Saussure's description, dating from the early decades of the eighteenth century, praises the many shop signs in the four ‘finest’ (80) streets for being ‘really magnificent’ and costly (81). The interest of passers-by might also be aroused through displays of goods in the shop windows, sometimes bow windows, inviting them to pause and look. Later in the century, some shops who had succeeded in enticing royal customers highlighted their status through sporting ‘“by appointment” crests’ (Berry 383) above their entrances. Inside the shop, pieces of furniture - counters, chests of drawers, and shelves - were placed. Recreational areas, sometimes with tables and chairs, invited groups of shoppers to sit, rest, talk, even have tea (Berg 269). In Frances Burney's novel Evelina (1778), Mr. Branghton's silver-smith's shop in London, described as ‘large and commodious’, also contains several chairs to this purpose.10 And Daniel Defoe, although highly critical of expensive shop decorations, nevertheless provides detailed advice in his Complete English Tradesman (1726) on the number of looking-glasses, candlesticks, and lanterns necessary for a fashionable interior,11 thereby highlighting its importance in the shopkeepers’ rivalry for well-to-do customers. A further source for interactions inside eighteenth-century shops are trade cards (Walsh), printed for advertising. They spotlight not only the goods on sale but also depict typical sale situations, involving customers and staff, and shop interiors. A trade card of the London paper manufacturer Masefield from the British Museum’s collection, dating from 1758, shows four persons, presumably two ladies of fashion, the shopkeeper or shop assistant, who is presenting a roll of paper, and another man.12 The two female customers examine and discuss the goods, while the seller is at their service. By discussing the merits of patterned paper, by setting their own taste against the commercial goods, the women also display their status to the observer. Beside and behind this scene are numerous shelves storing further paper rolls in ‘Masefield’s warehouse’, which sold ‘mock India paper hangings’ and was to be found in the Strand. Many eighteenth-century retailers traded goods which they themselves had partly or wholly produced, while so-called ‘warehouses’ served as salesrooms.13 The layout visible on the trade card shows that the spacious premises consisted of more than one room. A large window, mirrors, and artwork as well as the full shelves convey an impression of elegance and opulence, inviting groups of customers to browse and to linger. The trade card of the haberdasher Benjamin Cole at St Paul’s Church-Yard in London (c. 1720) also shows a fairly spacious shop, big enough to host a group of three female customers, two of whom are communicating with the sales staff over a large counter, where goods can be scrutinized, while the third customer is sitting in the back with her fan open, in a posture of relaxation.

Customers were invited to sit down, even take refreshments, or engage in conversation during their visit. The scrutinizing of the goods, which were placed before them, occurred in a relaxed atmosphere. Customers were invited to touch so that shopping also became an experience involving the senses.14

- 9. Claire Walsh, ‘Shop Design and the Display of Goods in Eighteenth-Century London’, Journal of Design History (vol. 8, n° 3, 1995), p. 157-176, p. 158.

- 10. Frances Burney, Evelina, or, A Young Lady's Entrance into the World [1778], ed. Susan Kubica Howard (Peterborough: Broadview, 2000), p. 283.

- 11. Daniel Defoe, The Complete English Tradesman (Edinburgh: Chambers, [1726] 1839), p. 62-63.

- 12. ‘Masefield's’, c. 1758, trade card. British Museum, online collection, Museum number Heal,91.41. 25 July 2021. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_Heal-91-41 . This image is also in Walsh, p. 163.

- 13. Wedgwood was another company using showrooms (Berg, p. 265-269).

- 14. Serena Dyer, ‘Shopping and the Senses: Retail, Browsing and Consumption in 18th-Century England’, History Compass (vol. 12/9, 2014), p. 694-703.

Female Shoppers and Goods

The central protagonists of recreational shopping were women, although not all shopping was done by them. Certain shopping rituals developed. Individuals went out together, often to several shops, as a leisure pursuit, which comprised several hours and included taking refreshments. Lydia Melford, one of the protagonists of Tobias Smollett's Humphry Clinker, describes the leisurely routine at Bath: ‘From the bookseller’s shop, we make a tour through the milliners and toy-men; and commonly stop at Mr. Gill’s the pastry-cook, to take a jelly, a tart, or a small bason of vermicelli’.15 Like the visits to the Pump Room, walks in the park, and evening entertainments, a shopping tour was a recreational activity and could take up a part of the day. Since shopping was sociable, it was important to dress adequately: ‘At the milliners, the ladies we met were so much dressed, that I should rather have imagined they were making visits than purchases’, Burney’s heroine Evelina muses while in London (118). The other customers were individuals one might meet again, in public spaces or during private invitations. Hence, shopping was a way of encountering others without formal introduction, of observing displays of taste and manners from a distance.

- 15. Tobias Smollett, The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, ed. Lewis M. Knapp, rev. by Paul Boucé (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 41.

Sometimes, female shoppers were stereotyped as disruptive and as spectacles.16 Issue 9 of The Female Tatler (1709) presents a group of women at Ludgate Hill, who spend hours looking at silks, and haggle and flirt with the sales assistants (‘the greatest Fops in the Kingdom’) before completing a purchase. Issue 67 accompanies three women to India House, where they observe other shoppers’ inappropriate behaviour: one woman who ‘drank a Gallon of Tea, and marched off without laying out Six Pence’, another searching for ‘finer things than were ever made’, wanting ‘them cheaper than they were bought’. Haggling (Berry 391), which eventually gave way to a system of fixed prices, was part of the sales process. The image of the disruptive female shoppers remained valid throughout the century, and is also used in a poetic epistle entitled ‘A Letter from Miss Grace Vizard, to Lady Bab Evergreen, at Bath’, published in the Universal Magazine (1770), which satirizes the sociable search for consumer items as female rapaciousness: ‘You know, a whole week, day and night, we went shopping;/ We ransack’d the town from St. James’s to Wapping.’17 Female shopping was fraught with cultural anxieties, among which the danger of financial ruin was looming large. Another fear was that polite shopping might turn into an erotic adventure. After all, sociable interaction occurred not only with other shoppers but also with the sales staff, who were reputed to use all kinds of persuasion, including flirting. Thus, the pitfalls of sociable shopping were frequently pointed out.

- 16. Jennie Elizabeth Batchelor, Dress, Distress and Desire: Clothing and Sentimental Literature, PhD (London, 2002), p. 98.

- 17. A Letter from Miss Grace Vizard, to Lady Bab Evergreen, at Bath’, Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure (vol. 46, n° 319, March 1770), p. 153. On the ‘undisciplined’ female shopper, see also Kowaleski-Wallace, p. 85.

The range of goods available in luxury shops encompassed clothing (textiles, millinery, gloves), domestic wares (china, decorative glass ware, tea-tables), or books. Certainly, joint shopping also entailed a shared sensuous experience. To the shopper, the acquisition and subsequent display of the right object signalled ‘taste’ and therefore status. Moreover, learning how to shop became ‘a form of enlightened knowledge’ (Berg 266). ‘Conspicuous consumption’, the display of goods acquired in order to cement one’s social status, was another extension of this shopping rituals, long before Thorstein Veblen coined the phrase.’18 Buying the right item was a necessary precondition for displaying this item – at home, or in sociable leisure spaces such as promenades and theatres, in the metropolis as in spas. Goods were frequently gendered: the display of certain material objects (china, textiles) was coded as female; women came to be compared to china, to its fragility and ‘weaknesses’ (Kowaleski-Wallace 53). Other luxury goods (for example, expensive books) were predominantly seen as male affairs.

In the early nineteenth century, shops grew in size, while their goods were increasingly ready-made and not produced by the shop-owner. London’s Burlington Arcade, opened in 1819, as well as other arcades hosted a number of small shops under one roof, thus continuing eighteenth-century forms of retail.19 At the same time, covered markets and bazaars became more popular, while the department store only emerged as a central shopping venue in the last decades of the nineteenth century.

Share

Further Reading

Berg, Maxine, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain [2005] (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007)

Berry, Helen, ‘Polite Consumption: Shopping in Eighteenth-Century England’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society (vol. 12, 2002).

Furnée, Jan Hein and Lesger, Clé (eds.), The Landscape of Consumption: Shopping Streets and Cultures in Western Europe, 1600-1900 (Houndsmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

Stobart, Jon, ‘Shopping streets as social space: leisure, consumerism and improvement in an eighteenth-century county town’, Urban History (vol. 25, n° 1, 1998), p. 3-21.

Vickery, Amanda, The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

Walsh, Claire, ‘Shop Design and the Display of Goods in Eighteenth-Century London’, Journal of Design History (vol. 8, n° 3, 1995), p. 157-176.