Abstract

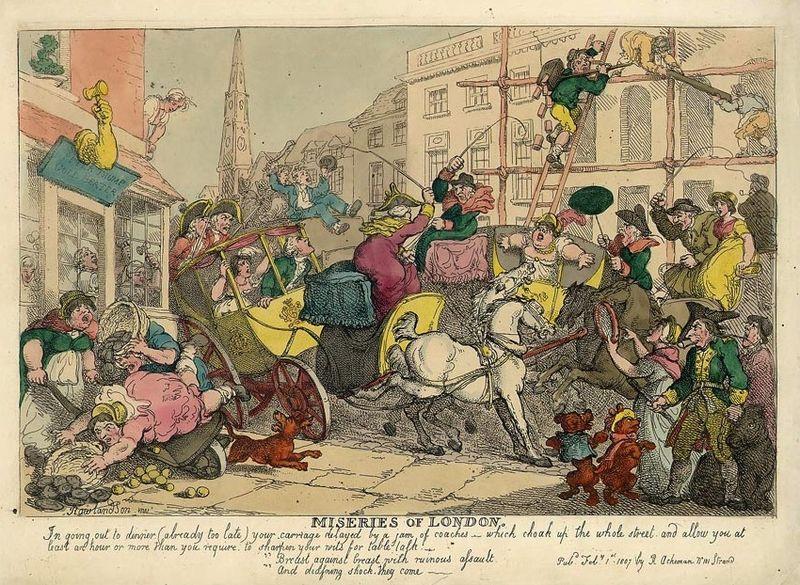

In a world of pedestrians streets and roads formed the most demotic of social spaces. In eighteenth-century Britain, it was on the street that gentlemen and gentlewomen rubbed shoulders with hawkers, paupers and a varied cast of social inferiors. The streets demanded new rules of behaviour, new ‘rules of the road’. By reference to the practice of everyday life, the evolution of literary representations of street life, and the development of new forms of regulation, this article explores the street as a uniquely complex site of social exchange and sociability.

In eighteenth-century British towns, almost everyone was a pedestrian. It was on the street that gentlemen met merchants, where artisans trudged alongside clerks, where women sold the necessities of the everyday; and where beggars cried for attention. The street was the club that admitted everyone. While the coffeehouse and the salon have exercised modern historians as the all-important sites of sociability, eighteenth-century commentators were just as fascinated by the sociability of the street, and especially with the streets of London.

These alfresco demotic spaces witnessed innumerable cross-class and cross-gender encounters that sit awkwardly at the intersection of several historiographical perspectives. In the work of Jürgen Habermas, the streets are largely absent. They sit beyond the walls of the coffeehouses and salons, where the newspapers were read and discussed by groups of self-selecting and socially uniform characters. For Habermas, this is where the real work of sociability and its ‘authentic public sphere’ took place. Indeed, he explicitly juxtaposes the creation of an extended form of public opinion through sociability, with ‘pressure from the street’.1 And yet, it is clear in the work of historians such as Penelope Corfield and Cynthia Wall, that eighteenth-century streets were performative spaces in which every address had its meaning, and every encounter its conventions, and where social mixing was at its most jumbled. Finally, in the work of Michel de Certeau and his followers, on the practice of everyday life, the streets emerge as complex structures designed to control behaviour and encounter - literally forcing pedestrians down pre-determined paths – that in turn forced them to develop opposing ‘tactics’ and ‘strategies’.2 These literatures suggest that the sociability of the street – the street’s role as the most democratic of social spaces – is central to eighteenth-century sociability; and yet inadequately embedded within the broader relevant literature.

The importance of social encounters in the street did not escape eighteenth-century commentators. From Marcellus Laroon's Cryes of the City of London drawne after the Life 1678), to Defoe’s Moll Flanders and Colonel Jack (1721) a new fascination with streets and street life can be observed.3 This evolving literature is exemplified in No. 545 of The Spectator (1711-14), describing 24 hours on the streets – with its cast of freshly observed human types, and varied joys and tribulations, and in Jonathan Swift’s Description of a London Shower (1710).4 It reached a kind of early apotheosis in John Gay’s monumental Trivia: Or, the Art of Walking the Streets of London (1716). In these works, the streets themselves emerge as sites of both sociability and conflict, excitement and danger. Trivia forms a 417-line long guide how:

THROUGH Winter Streets to steer your Course aright,

How to walk clean by Day, and safe by Night,

How jostling Crouds, with Prudence, to decline,

When to assert the Wall, and when resign.5

As the eighteenth century progressed, the centrality of social encounters on streets and roads simply grew. The privatized turnpike roads of Britain’s countryside took one route towards a new and regular form; while the public streets of the town took another. In Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones – and in a dozen other picaresque novels – form, plot and tension are provided by ever more varied social encounters on both urban streets and country roads.6 Building on the format of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, in the works of Fielding, Smollett and Laurence Sterne, the ‘journey’ through roads and streets is used to unify the narrative.7 In the process, the main character is forced to navigate an ever more diverse landscape of people, and to socialise along the way. This literary tradition led in turn to Pierce Egan and the phenomenon that was Life in London (1818) chronicling the adventures of Tom, Jerry, and Bob Logic, in which the streets of London, and by imaginative extension, the new built streets of Britain’s other major cities, provide the backdrop for a modern comedy of manners in which ever more complex social codes are negotiated (or not).8 This strand of literature would eventually result in the creation of the figure of the flâneur, but from its origins in the late seventeenth century to the first quarter of the nineteenth century, it allowed contemporaries to view their streets as sites of constant encounter and constant challenge.9

- 1. Jürgen Habermas and Thomas Burger (translator), The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002), p. 233.

- 2. Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, 3rd ed. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011).

- 3. Marcellus Laroon and Sean Shesgreen (ed.), The Criers and Hawkers of London : Engravings and Drawings (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1990); Daniel Defoe, The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1978); Daniel Defoe and S. H. Monk, The History and Remarkable Life of the Truly Honourable Col Jacque (Oxford: OUP, 1965).

- 4. ‘No. 454, Monday, August 11, 1712’, Richard Steele and Joseph Addison, Spectator, 1711-1714, ed. D.F. Bond, 5 vols (Oxford, 1965); Jonathan Swift, ‘A Description of a City Shower’ (1711), ed. Roger Lonsdale, The New Oxford Book of Eighteenth-Century Verse (Oxford: OUP, 1984), p. 16-17.

- 5. John Gay, Trivia: Or the Art of Walking the Streets (1716), Book 1, lines 1-4. See Clare Brant and Susan E. Whyman (eds), Walking the Streets of Eighteenth-Century London: John Gay’s Trivia (Oxford: OUP, 2009).

- 6. Garrido Ardila, J., ‘The picaresque novel and the rise of the English novel: From Baldwin and Delony to Defoe and Smollett’, in J. Garrido Ardila (ed.), The Picaresque Novel in Western Literature: From the Sixteenth Century to the Neopicaresque (Cambridge: CUP, 2015), p. 113-139.

- 7. See Ronald Paulson, Don Quixote in England: The Aesthetics of Laughter (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998).

- 8. Pierce Egan, Life in London or, the Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorn, esq., and his elegant friend, Corinthian Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, the Oxonian, in their rambles and sprees through the Metropolis (1821), adapted for the stage by William Thomas Moncrieff, as ‘Tom and Jerry, Or Life in London’.

- 9. Rick Allen, The Moving Pageant: A Literary Sourcebook on London Street-Life, 1700-1914 (London: Routledge, 1998).

It was not merely that the urban streetscape was a location of imaginative journeying. In law, governance and regulation, and in non-fiction accounts, streets in particular took on an ever more central place. Rebuilt in pursuit of what Peter Borsay has characterized as an ‘urban renaissance’, streets became more regular, better paved, and better lit.10 From the 1690s movements including the Societies for the Reformation of Manners sought to police street behaviour – including swearing and prostitution.11 ‘Highway robbery’ also emerged as a distinct category of crime in the same decade, including a uniquely generous set of rewards, and an associated romantic culture. Most crimes prosecuted under these laws did not involve horses and a demand to ‘stand and deliver’. Instead they were what would now be thought of as muggings on city streets – in which intra-class conflict was played out.12 The rewards and awful punishments meted out reflect anxiety about who one might meet on the streets.

- 10. Peter Borsay, The English Urban Renaissance: Culture and Society in the Provincial Town, 1660-1770 (Oxford: OUP, 1991).

- 11. Faramerz Dabhoiwala, ‘Sex and Societies for Moral Reform, 1688-1800’, Journal of British Studies, 2007: 46(2): 290-319.

- 12. Gillian Spraggs, Outlaws and Highwaymen: The Cult of the Robber in England from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century (London: Pimlico, 2001).

Similarly, the incorporation of the ‘mob’ into the workings of the political nation up until 1780 and the Gordon Riots – created a plebeian veto on unpopular initiatives, that was again played out on the street between the rich, the middling sort and working people.13 And perhaps most obviously, in prostitution, the street formed the locus of negotiation and exchange – with figures such as James Boswell, adopting a range of different personae depending on whose services he sought and what streets he went down.14 Deciding to whom to tip a hat, or offer a hand; to whom to give up the wall, or gingerly avoid; whether to walk arm in arm, eyes raised to meet an approaching stranger, or alone, eyes cast down to avoid stepping in dirt. Whether you held your skirts above the mud, or kept a hand by your side to protect your pocket, each choice and action was both a practical response – a tactic in de Certeau’s sense – and a gestural form of communication directed at all the other members of this club of the streets.

When Erasmus Jones published his Man of Manners: Or Plebeian Polished in 1737, for the ‘benefit of persons of mean birth and education’, his first order of business was to detail ‘The Manner of walking the Streets and other Publick Places’; and how to greet the friends and acquaintances, ‘low fellows’ and the beggars you met on the pavement. Jones included a long list of phrases to be avoided, actions eschewed, and tones to be adopted – all aimed at reforming the shared culture of street sociability.15

- 15. Erasmus Jones, The Man of Manners: or, Plebian Polish'd. Being Plain and Familiar Rules for a Modest and Genteel Behaviour ... (1740), p. 1-5.

The streets did not provide a locale for the easy social interaction of the coffeehouse or drawing room. The streets did not allow for a sociability of sameness – though the royal parks and gay cruising grounds were exclusive enough. Instead, the streets confronted you with difference, and forced you to navigate that difference – to perform your role in the varied pageant of the roadway. In an ever more complex code; in an ever more ginger negotiation between individuals; the eighteenth century developed a unique and complex form of sociability. The ‘rules of the road’ evolved to allow the gentleman, and gentlewoman to talk to beggars and hawkers; to share words and opinions; to both police the difference between them, and to bridge that difference. This particular ‘public sphere’ was where intra-class and inter-gender relationships were most fully negotiated. As David Hume observed in 1758: ‘They cannot even pass each other on the road without rules.’16

- 16. David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1751), Section IV. ‘Of Political Society’.

Share

Further Reading

Allen, Rick, The Moving Pageant: A Literary Sourcebook on London Street-Life, 1700-1914 (London: Routledge, 1998).

Brant, Clare and Whyman, Susan E. (eds), Walking the Streets of Eighteenth-Century London: John Gay’s Trivia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

Corfield, P. J., 'From Hat Honour to the Handshake: Changing Styles of Communication in the Eighteenth Century', in P. J. Corfield and L. Hannan (eds.), Hats Off, Gentlemen! Changing Arts of Communication in the Eighteenth Century/ Arts de communiquer au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2017), p. 1-22.

Guldi, Jo, 'The History of Walking and the Digital Turn: Stride and Lounge in London, 1808–1851', The Journal of Modern History (vol. 84, n° 1, March 2012), p. 116-144.