Abstract

William Gilpin’s name is commonly associated with the notion of the picturesque. If his search for picturesque beauty was central to most of his life, it was more a solitary activity than a collective one. Gilpin’s experience of sociability was first and foremost epistolary and literary. However, the headmaster tried to prepare his pupils for a sociable life and imagined a sociable life after death.

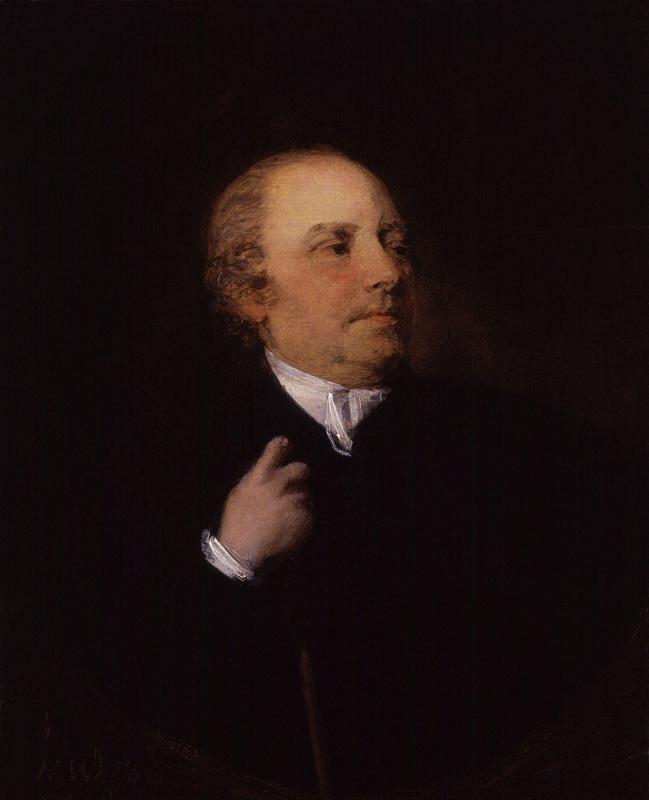

William Gilpin (1724-1804) was a clergyman, ordained deacon in 1746, first appointed to the curacy of Irthington in Cumberland, who received full orders in 1748. In 1777, he became vicar of Boldre in the New Forest, Hampshire, a position which he was to hold until the end of his life. But William Gilpin was also a respected and enlightened headmaster, with a BA (1744) and a MA (1748) obtained at Queen's College, Oxford, who was in charge of the management of the Cheam School for Boys, in Surrey, from 1753 to 1777. Although he wrote in his memoirs that these two careers were the ‘only two transactions of his life which could fairly claim the attention of posterity’,1 his name is nowadays more often remembered as that of the inventor of the aesthetic notion of ‘picturesque beauty.'

While little material is available about William Gilpin’s sociable connexions and activities, his aesthetic essays, his autobiographical writings and letters help to qualify the image of the asocial theoretician of the picturesque. Even if he was not prone to socializing, which can partly be explained by the excesses of many male social gatherings which he denounces in some places, the headmaster still estimated that his role, when educating young pupils, was to prepare them to live in society.

- 1. William Gilpin, Memoirs of Dr. Richard Gilpin … and of his posterity … together with an account of the author, by himself: and a pedigree of the Gilpin family, ed. W. Jackson (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1879), p. 147-148.

An unsociable relative and friend

William Gilpin’s letters to his son and grandson clearly show his deep interest in family matters and concerns. However, in several places, his passive and active correspondence provides images of a rather unsociable man,2 who did not enjoy the company even of his relatives, while he relished conversing with them in his letters. When his grand-children visited him, he kept to his study.3 With his friends, he preferred epistolary exchanges to conversation as his son William explained bluntly in an unpublished note kept at the Bodelian library:

Some of my father’s intimate acquaintance he never saw. They respect him for his works, and write to him. Thus, an intercourse commences. And I have heard him say that possibly their acquaintance is best cultivated at a distance and that they might like each other’s hand-writing better than their persons.4

- 2. For a definition of ‘unsocial sociability’ as the human ‘propensity to enter into society, bound together with a mutual opposition which constantly threatens to break up society’, see Kant, ‘Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Viewpoint’, Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 44.

- 3. William Gilpin, William Writes to William: The Correspondence of William Gilpin (1724-1804) and his Grandson William (1789-1811), ed. A. Kerhervé (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014), p. 69.

- 4. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Eng. Misc. f. 202.

In a similar vein, his letters to Mary Delany (1700-1788) highlight the difficulties he encountered with keeping on friendly terms with some of his correspondents, because of his excessive reactions, as can be seen when he wrote to her on 13 May 1782:

Some people are never to be satisfied; you shewed my papers to a friend or two — I flew into a violent rage — you immediately returned them — now I vibrate as far into a contrary passion. I am mortified to the last degree, lest, in my rage, I should have said some thing improper, and have offended you?5

Similarly, he initiated some tension with William Mason, his long-time friend and editor, on having suggested that the latter was too sociable a person to spend the winter out of London:

Vicar's Hill, June 13th, 1782. / Dear Madam, / I had a letter this week from Mr. Mason, who does not intend, I find, to visit London this year. He is very angry with me for supposing he could not spend a winter by his own fire-side at Aston; indeed, I fancy 'd that if nothing else would have brought him to town, the pleasure of seeing all his friends uniting to restore the nation would have had its influence; but he tells me he has been better employ 'd in putting up a Gothic window in the chancel of his church, than he should have been in running from one levee to another. (Mary Granville 91-92)

The unsociable correspondent preferred written conversation to meetings. In an 1801 letter, he explained how he managed to cope with the afflux of visitors he had to deal with because of his official function:

- 5. The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany, ed. Lady Llanover (London, R. Bentley, 1861-1862), vol. 6, p. 86.

I am obliged to see more company than I wish: but I have a kind friend, who manages things dexterously for me. I commonly sit in my bow-windowed parlour below stairs, and all company is carried into the drawing-room above; and such company as I wish to see, or want to see me, she sends down to me.6

In his Memoirs, written in the third person, he insists on his choice of limited social interactions.

He neither gave, nor received invitations to dinner. He was surrounded by rich neighbours, who were continually making handsome entertainments. He was glad to receive a friend at dinner in a family way; or a neighbour to drink tea: but the expence of entertainments — the loss of time they occasioned, which in large mixed companies is seldom made up by any thing but a good dinner – and the bustle they throw a little family into – were all reasons with him for avoiding such engagements. […] But tho he did not unite in any of these scenes of festivity, he could speak with assurance that he never gave offense to his neighbours by his refusal. Refusing all, he disobliged none. Indeed as neither he, nor his wife, played at cards, they conceived they might often be disagreable intruders. (Gilpin, Memoirs, 150)

- 6. Rebecca Warner, Original Letters from Richard Baxter, Matthew Prior, Lord Bolingbroke, Alexander Pope, Dr. Cheyne, Dr. Hartley, Dr. Samuel Johnson, Mrs Montague, Rev. William Gilpin, George Lord Lyttleton, Rev. John Newton, Rev. Dr. Claudius Buchanan, &c., &c. (London: R. Cruttwell, 1817) p. 172-173.

Logically enough, the letters he exchanged with William Mason, Mary Delany and his grandson William largely focus on his solitary relationship to nature, from his daily observation of squirrels and birds at home (Gilpin, William writes to William, 2, 8, 24, 44) to his concern for the publication and reception of his essays on picturesque beauty.7

- 7. Bodleian Library, Ms. Eng. Let. 6. 27, 43, 49, 51

A socializing holiday-maker?

In the Summer holidays (Gilpin, Memoirs, 135), William Gilpin often embarked on tours in search of picturesque beauty in several parts of Great-Britain (South Wales in 1770, Cumberland and Westmoreland in 1772, Hamphshire, Sussex and Kent in 1774, High-lands of Scotland in 1776), for which he accounted in his notebooks, which were published in the 1780s and 1790s in several essays of ‘observations’. The satirical accounts that were afterwards made of his travels and cartooned by Rowlandson show the clergyman, Dr Syntax, at several social gatherings, putting in at inns, enjoying banquets, watching a military review or attending horse races.

However, most of his essays are totally void of any mention of sociability with human beings, as predictable from the first page of his 1770 Observations on the River Wye, and several parts of South Wales (first printed in 1782):

We travel for various purposes —to explore the culture of soils — to view the curiosities of art — to survey the beauties of nature — and to learn the manners of men; their different polities, and modes of life. / The following little work proposes a new object of pursuit; that of examining the face of a country by the rules of picturesque beauty.8

And yet, some forms of sociability appear in his representations of nature under the presence of horses, which were not, to him, picturesque animals, contrary to cows9 but had to be taken good care of since they belonged to man’s sociable world and complemented or helped social interactions. In his Three Dialogues on the Amusements of Clergymen, one understands that a horse can provide companionship to a contemplative clergyman:

- 8. William Gilpin, Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales (London : Printed for R. Blamire, sold by B. Law and R. Faulder, 1782.), p. 1.

- 9. William Gilpin, Observations, Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty, Made in the Year 1772: On Several Parts of England; Particularly the Mountains, and Lakes of Cumberland, and Westmoreland (London : Printed for R. Blamire ..., 1786), p. 262.

The very trot of a horse is friendly to thought. It beats time, as it were, to a mind engaged in deep speculation. An old acquaintance of mine used to find its effect so strong, that he valued his horse for being a little given to stumbling. I know not how far, he would say, I might carry my contemplation, and totally forget myself, if my honest beast did not, now and then, by a false step, jog me out of my reverie; and let me know, that I had not yet gotten above a mile or two out of my road.10

In Remarks on forest scenery, the New Forest horse is seen to adapt very well to human activities, to hold a prominent part in collective activities and to be celebrated for it.

- 10. William Gilpin, Three Dialogues on the Amusements of Clergymen (London: printed for B. and J. White, 1796) p. 154-156.

The fame, and exploits are still remembered of a little beautiful, grey horse, which had been suffered to run wild in the forest, till he was eight years of age; when he had attained his full strength. His first sensations, on the loss of his liberty, were like those of a wild-beast. He flew at his keeper with his open mouth; or rearing on his hind legs, darted his fore-feet at him with the most malicious fury. He fell however into hands, that tamed him. He became by degrees patient of the bit, and at length suffered a rider. From this time his life was a scene of glory. He was well known on every road in the county; was the favourite of every groom; and the constant theme of every ostler. But in the chase his prowess was most shewn. There he carried his master, with so much swiftness, ease, and firmness, that he always attracted the eyes of the company, more than the game they pursued.11

- 11. William Gilpin, Remarks on forest scenery, and other woodland views, (relative chiefly to picturesque beauty) illustrated by the scenes of New-Forest in Hampshire. In three books. (London: printed for R. Blamire, Strand, 1791), vol. 2, p. 253-254.

Finally, in his later years, at a time when he was devising an essay entitled ‘On horses and domestic fowls’, in 1803,12 William Gilpin made horses, cutting some out of cardboard and painting them, and used them to make his grandson understand some forms of sociability. The grand-father and grand-son occasionally refer to Sawrey Gilpin’s drawings and paintings of horses, including scenes showing riders conversing on their horses and imagine many stories involving the characters of the animals living in polite and intelligent company with human beings.

- 12. The manuscript is held at the Bodleian Library, Ms. d. 566 (‘On Horses and Domestic Fowls’). It bears the mention: ‘Vicar's Hill, Aug. 18, 1803. ‘These two volumes […] belong to my grandson William Gilpin of Cheam.’ It is a kind of illustrated catalogue or dictionary containing different types of horses and fowl.

A headmaster preparing his pupils for society

William Gilpin’s letters to his grandson and his epistolary manual13 harp on the diffidence young men should have of male sociability, using several examples of innocent youth led to extremes and occasionally death for allowing himself into the company of misfits. While the manual insists that the young man is initially good by nature, he occasionally meets people who drive him off the right track. Among the excesses he can become a victim of lies or excessive alcohol consumption as denounced by a young soldier reacting to his Colonel’s enticing his men to drink (Gilpin, Letter-Writer, 20). Although the soldier writing to his father initially resists temptation, to his father’s delight, and assures him that he can resist the collective pressure of a group of men, he eventually yields to temptation, but it leads him to his death since he is killed when trying to enter a convent in which he wanted to meet the young woman he was trying to seduce. Once again, it was not his nature, he was enticed by a friend to follow the young woman (Gilpin, Letter-Writer, 61). Among the other bad habits identified in company, many men swear (17, 127, 131) and spend money on such vices as game or alcohol, but also on nice clothes (94-97). The social game also leads to duels, a condemnable practice in William Gilpin’s words, as he expresses in two letters of the manual (20, 70), and in many other writings.14 It should then not be surprising that some men, blinded by that sociable world of leisure and appearances end up in a state of complete destitution. Consequently, the threat of those masculine ills should be learnt from their early youth, by stressing the importance of the attitude at school (Gilpin, Letter-Writer, 133). In William Gilpin’s words, scholarly education is thus perceived as the means to learn social life and must be understood by young children. Teaching how to live together in society was one of the main concerns of the headmaster in his school at Cheam. In order to do so, he established a real ‘state’ (Gilpin, Memoirs, 127) or ‘miniature of the world’ (128) in which the boys not only attended classes but cultivated their own gardens, became ‘landholders, tradesmen and public officers’ (128), learnt to live together in a society where little place was left to leisure activities but respectful interactions between individuals were constantly promoted.

- 13. William Gilpin, William Gilpin’s Letter-Writer, ed. A. Kerhervé (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014).

- 14. That is frequent in William Gilpin’s writings whether in his letters to his grandson or in his essays. See, for instance, William Gilpin, Dialogues on Various Subjects (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1807) p. 217-252 (‘On duelling’) and Bodleian Library, Ms. Eng. Misc. d. 569, fol. 210, letter to his son William, 22 March 1796: ‘I began lately a little dialogue on duelling’. Also see Ms. Eng. Misc. e. 518, fol. 73 and fol. 77.

A philanthropist and a clergyman imagining sociability in the afterlife

In 1777, William Gilpin left Cheam to become vicar of Boldre in the New Forest, Hampshire. There, he was involved in the construction and support of two schools – one for boys, one for girls – at Boldre (Gilpin, Memoirs, 144) which he intended to be for the poor who would otherwise have no access to education and which, as he made sure in his will,15 would survive him. However, in 1799, five years before his death, he received a letter from the painter Mary Hartley in which his friend tries to understand, by rephrasing and quoting some of the clergyman’s previous statements, William Gilpin’s conception of sociability in the afterlife (Warner 158-163):

I have been looking back at your old letters, when we first discussed the subject of re-union with friends in a future state; and I must ingenuously confess, that I have done injury to your sentiments, in saying, that you seem to think there is no foundation for the hope of seeing and knowing our friends again in a future state. On the contrary, I see, that in those letters you speak of it as highly probable, ‘that we shall unite hereafter with those with whom our souls have been connected here’ but then you think that I lay more stress upon this enjoyment than it deserves. (Warner 159)

Thus the Reverend Gilpin imagines that friends, i.e. the persons with whom tight links have been developed, will meet again in the afterlife, even though some connections may disappear and new ones be born:

Yet we are told, that we are to be associated with ‘the spirits of just men made perfect;’ that ‘we are not to grieve for our departed friends, as those would do who have no hope.’ This certainly conveys an idea, that we shall meet them again: but I agree with you entirely, that, in many cases, it is probable, the attachments of this world, and those of the next, may not coincide. […] These hasty friendships, and all friendships that are not built upon virtue, will certainly be dissolved. (Warner 161)

William Gilpin’s vision of ‘people living in unison with others’ both recalls Locke’s description of society and suggests scenes of ideal sociability.

There will be no jealousy, no envy, no wish for pre-eminence, in heaven. All will love God with their utmost powers, and all will love their fellow-creatures as themselves, enjoying happiness in unison with others, and not wishing for peculiar favour, even from God, to themselves individually. (Warner 162)

- 15. See The National Archives, Kew, PROB 11/1408/233 , ‘Will of Reverend William Gilpin, Vicar, Clerk of Boldre , Hampshire’, 12 May 1804.

Share

Further Reading

Andrews, M., ‘Gilpin, William (1724–1804)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://doi-org.janus.bis-sorbonne.fr/10.1093/ref:odnb/10762.

Aske, Katie and Page-Jones, Kimberley (dir.), La sociabilité en France et en Grande-Bretagne au Siècle des Lumières. Tome 6: L’insociable sociabilité: résistances et résilience (Paris : Le Manuscrit, 2017).

Barbier, C. P., William Gilpin: His Drawings, Teachings, and Theory of the Picturesque (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963).

Gilpin, William, Memoirs of Dr. Richard Gilpin … and of his posterity … together with an account of the author, by himself: and a pedigree of the Gilpin family, ed. W. Jackson (London: B. Quaritch 1879).

Gilpin, William, William Gilpin’s Letter-Writer, ed. A. Kerhervé (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014).

Gilpin, William, William Writes to William: The Correspondence of William Gilpin (1724-1804) and his Grandson William (1789-1811), ed. A. Kerhervé (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014).

Templeman W., ‘The Life and Work of William Gilpin (1724–1804), Master of the Picturesque and Vicar of Boldre’, Illinois Studies in Language and Literature (vol. 24, n° 3-4, 1939).

Warner, R., Original Letters from Richard Baxter, Matthew Prior, Lord Bolingbroke, Alexander Pope, Dr. Cheyne, Dr. Hartley, Dr. Samuel Johnson, Mrs Montague, Rev. William Gilpin, George Lord Lyttleton, Rev. John Newton, Rev. Dr. Claudius Buchanan, &c., &c. (London: R. Cruttwell, 1817).

![Doctor Syntax, Rural sport (1 May 1812) by Thomas Rowlandson (1757 - 1827) taken from [W. Combe], The Tour of Doctor Syntax in Search of the Picturesque, London 1812, pl.20.](/sites/default/files/styles/notice_full/public/2024-02/WILLIAM%20GILPIN%20Doctor%20Syntax.png?itok=lMWicCUY)

![Doctor Syntax, Rural sport (1 May 1812) by Thomas Rowlandson (1757 - 1827) taken from [W. Combe], The Tour of Doctor Syntax in Search of the Picturesque, London 1812, pl.20.](/sites/default/files/styles/wysiwyg_full/public/2024-02/WILLIAM%20GILPIN%20Doctor%20Syntax.png?itok=Nme2cPl4)