Résumé

The dismantling of collections attracted a growing audience to the auctions, which took on complementary roles as exhibition venues. Crucially, these urban landmarks enabled a social and visible valuation of artefacts. Behind the scenes, auctioneers offered services that professionalized the art market (as brokers, appraisers and upholsterers). As commerce evolved from an early modern market based on reputation and personal ties to commerce liaised by middlemen, the auction house connected collectors of varied social backgrounds, contracting on their behalf an array of services (frame-makers, picture-restorers and dealers) both in the city and internationally, and becoming a hub of connoisseurial debate.

Mots-clés

Auction sales were imported from seventeenth-century Holland, but rapidly became a feature of the British market, and as they specialized in sales of cultural goods, they shifted from multipurpose commercial premises to purpose-built exhibition and sales venues – the auction house.

This spatial shift isolated the practice of bidding for artefacts and enabled a typically eighteenth-century ‘sociable co-operation in the field of commerce’ that saw politeness be renegotiated as a cultural practice of both taste and valuation.1 As the century unfolded, the auctions sales relocated from the Royal Exchange and its networks of wharfs and warehouses to the artistic clusters of Soho and Covent Garden and later on flourished in the West End and Pall Mall, completing their transition from commercial venues to fashionable haunts.

- 1. Mascha Hansen, 'Introduction', in Sebastian Domsch and Mascha Hansen (eds.), British Sociability in the European Enlightenment: Cultural Practices and Personal Encounters (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), p. 1–12.

Urban sociability to settle the price of cultural goods

Witnessing a Custom house sale of ships ‘by inch of candle’2 in 1662 London, Samuel Pepys recorded the rumpus caused by the novel method of auction: ‘After dinner, we met and went to see sold the Weymouth Successe and Fellowship Hulkes where pleasant to see how backward men are at first to bid; and yet when the candle is going out, how they bawl and dispute afterwards who bid the most first’.3 However chaotic the social gathering, brokers and upholsterers were quick to pick up that audience members bidding against each other was a fitting method to sell unstandardized goods.

Early modern market systems had long relied on prolonged negotiations and sustained one-to-one contacts – the auction, however, was built for speed and crowd. Soon, auctions left the confines of the port’s Prize-Office and the Common Crier’s office and started taking place in key centres of sociability – the coffeehouses.4 In England and Ireland, this was a transgression of sorts, as public sales of goods were often controlled by a monopoly. In Scotland, for example the town council control over such sales remained in effect all through the century.

- 2. This sale method was used for ‘Cargo of foreign goods […] to make a speedy Sale […] none shall bid less than a certain Summ more than another has bid […] about an inch of Wax-Candle is burning and the last bidder when the Candle goes out has the Lot,’ John Worlidge, Dictionarium Rusticum & Urbanicum (London: J. Nicholson, 1704) entry: inch of candle, unpaginated.

- 3. Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, ed. Robert Latham and William Matthews (London: Bell and Hyman, 1990), Vol. III, p. 185 [September 3, 1662].

- 4. Brian Cowan, 'Art and Connoisseurship in the Auction Market of Later Seventeenth-Century London,' in Neil De Marchi and Hans J. van Miegroet (eds.), Mapping Markets for Paintings in Europe, 1450 – 1750 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2006), p. 263–84.

Public sales of goods were increasingly made up of household goods after decease. As the household consumption of paintings, mirrors, porcelains, and books expanded, these hard-to-price objects became a non-negligible part of after decease transfer of capital. Auctions at coffeehouses such as Tom’s in London, or Dick's in Dublin offered a unique mode of urban sociability and exchange for these artefacts, as explained by the bookseller and auctioneer Edward Millington in 1689: ‘I have of late made several Sales of Prints, Paintings &c. upon different and more justifiable methods than were before practiced in the City of London, [...] kindly received and freely received by the great number of persons that were present of all qualities’.5 Coffeehouses enabled the meeting of commerce and a post-courtly elite, as the merchants’ efforts to disseminate these artefacts were met by the amateurs’ discursive strategies to categorize and classify them.6 Rapidly, urban artistic clusters developed dedicated rooms for these sales, such as Christopher Cock’s great rooms on the Great Piazza, Covent Garden, or the nearby Mr. Hutchins’ communicating rooms between Hart street and King Street. By the middle of the century, if the bulk of the trade in books, paintings and antiquarian items still happened on the private circuit through private sales and agents, the auction room had become a vital urban landmark which raised the profile of collectible goods and collectors alike.

Connections across the social divide

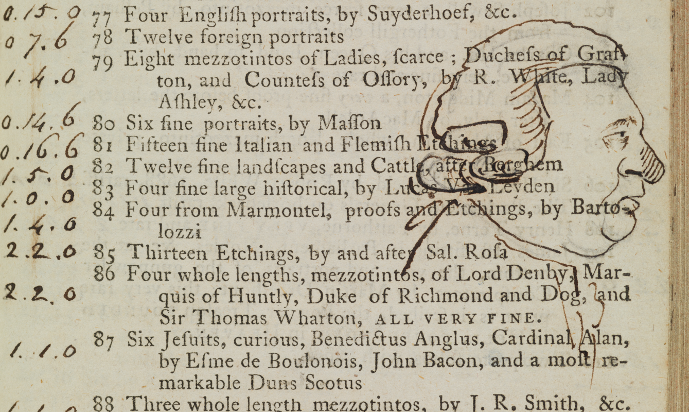

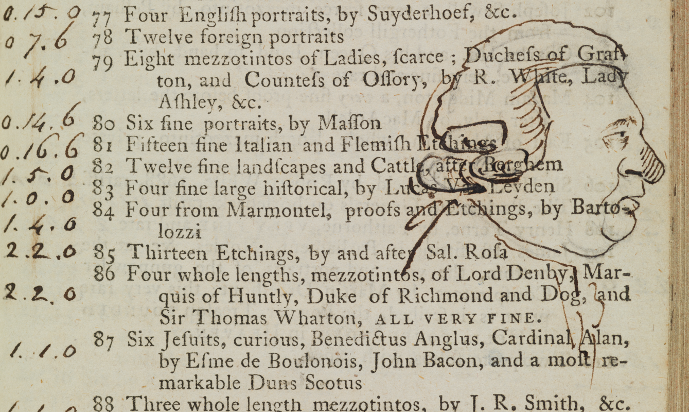

The auction room sociability was two-fold – both commercial and fashionable. It was a professional hub that enabled transactions across social divides between collectors and art professionals thanks to the auctioneer at the centre of this web of commerce. Since the emergence of an early modern marketplace, the valuation and resale of a multitude of objects had been an important side business of most cultural goods shops, as the terms tucked at the bottom of most of their trade cards testify: ‘Buys and Sells all manners of […]’ or ‘Most money for […]’. The auction rationalized and centralized this secondary market, accelerating and fluidifying the flow of objects. While names of well-known connoisseurs adorned the catalogues of library and collection sales, the items on show often met a wide array of budgets and interests since the sales were also stocked by professional frame-makers, picture cleaners, dealers, and booksellers. The auction house also connected the collector to a web of subcontracted professionals who stretched canvases, revarnishing, or framing, whilst also connecting the gentry and their country and town houses to the services of appraisal, hanging and inventory. Coffeehouses had been ‘centers of criticism – literary at first, then also political – in which began to emerge, between aristocratic society and bourgeois intellectuals, a certain parity of the educated’.7 As such, auction rooms seem to have proved very beneficial to communities of specialist knowledge, such as antiquarians and book collectors. This sociability of connoisseurs who often became auction regulars is still visible in the annotated pages of sales catalogues in which fellow bidders have been memorialized in the margin, forever linked to the lot descriptions and the prices paid.

- 7. Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. Thomas Burger (Cambridge, Mass: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1991), p. 32.

The auction house provided these communities with sociable space, by also maintaining and redistributing their cultural identities from sale to sale. The British antiquary and herald John Ive lived happily retired in Great Yarmouth and maintained his links with the Society of Antiquaries and the London Royal Society mainly by correspondence, but the sale of a fellow antiquarian’s collection would see his community converge to the auction room. ‘I cannot learn that the late Mr. West has left any will which makes me presume his valuables will come under the auctioneer’s hammer– if so I hope it will bring you with my other Yarmouth friends to Town’.8 The auction house pursued this ideal of sociable parity and community, making it the very motor of its spectacle, as bids that settled the price and ownership of artefacts were supposedly taken from the crowd indiscriminately – meaning without reserve settled between seller and auctioneer, or pre-sale deals to rig the bids between buyers.

- 8. Letter of John Ive, July 29th 1772, Lewis Walpole Library MSS4 Series 1, Box: 1, Folder: 18.

Fashionable Pall Mall

The auction house as a venue concentrated the crowd during viewing days and sale days in a show of genteel participation to the cultural marketplace. The auctioneer, perched on his rostrum orchestrated the biddings with his hammer. He had become a key agent in the growing pleasure the urban elite experienced in accumulating objects. The lots he attributed both fuelled polite conversation and provided the décor for sociable meetings. Auction doubled as a spectacle where people looked at unique artefacts while observing how other bidders’ appraised them, prompted by the cataloguer’s descriptions and guided by the auctioneer’s calls. Like the exhibition rooms and galleries that later flourished in their vicinity – and at the beginning often renting the same premises – the auction houses were a complementary venue for viewing art. Some auction houses narrowed further the selection of bidders invited to participate in the public valuation. ‘Great rooms’ such as Langford’s, Ansell’s, Bastin’s, Squibb’s or Skinner and Dyke’s became part of the fashionable town life as they increasingly advertised their gentility in the newspapers and started using ushers to regulate crowds, while some made 1-shilling catalogues compulsory for entry. By the second half of the century, the most famous auction houses nestled comfortably in the networks of exclusive clubs, sought after entertainment venues and exhibitions rooms in Pall Mall and the West End. Charles Jenner in his Town Eclogues (1772) depicted the young lady of fashion going about her London social routine:

In one continual hurry rolled her days,

At routs, assemblies, auctions, op’ras, plays,

Subscription balls and visits without end,

And poor Cornelys owned no better friend.

From Loo she rises with the rising sun,

And Christie sees her aching head at one.9

- 9. Charles Jenner, ‘Town Eclogues’, The British magazine (London: [s.n.], 1772), p. 444.

Auctioneers innovated as they sought social cachet. This meant a change of schedule for most picture and luxury goods sales. They changed to mid-day, the sociable hour of town visits, whereas they had mostly been held in the evening in Cornhill coffeehouses, to accommodate merchants leaving the Royal Exchange at closing time. The audience, from elite collectors to the middling sort, sought a fashionable experience and while many stock-of-trade and dealer-to-dealer sales continued to operate in winter, many fashionable art auctions coincided by the end of the century with the summer exhibitions of the Royal Academy and the fashionable season of London society.10

- 10. Pamela M. Fletcher and Anne Helmreich, ‘Local/ Global: Mapping Nineteenth-Century London’s Art Market’, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide (vol. 11, n° 3, 2012).

Making the auction fit for fashionable sociability meant significant investment in the architecture of the sale room, with purpose-built showrooms, premises expanding in the back garden, or lantern light built in the roofs for the better exhibit of pictures in particular. One of the first skylit venues was the auctioneer Aaron Lambe’s ‘Great New Rooms’ in Haymarket, later rented by the Free Society of Artists for their first exhibitions. Springing up in the urban landscape, these ‘halls are lofty, spacious’ and testified to the auctioneers’ ‘excessive care which they take to consult the purchaser’s ease’ according to the French traveler Jean André Rouquet, who further noted that ‘nothing can be more entertaining than this sort of auctions; the number of the persons present, the different passions which they cannot help shewing in these occasions, the pictures, the auctioneer himself, and his rostrum, all contribute to diversify the entertainment’.11

- 11. Jean André Rouquet, The Present State of the Arts in England. By M. Rouquet (London: J. Nourse, 1755), p. 121-126.

The entertainment factor was essential to auctions’ success. As such, auctions became features of spa towns, for example. Edward Millington would transfer his auctioneering talents from Barbadoes’ coffeehouse in London to the Auction coffeehouse in Tunbridge Wells during the tourist season. It is however important to complicate how sociability and pleasure consumption were tied in the auction house, just as they were in watering places. Spas attracted shady entrepreneurs and sparked gaming craze, and far more than a simple commercialisation of leisure was at work.12 Auction houses likewise came to dominate the secondary market thanks to an unprecedented influx of money and represented an opportunity for speculation. Family fortunes were disseminated, and family seats emptied in front of an audience that remained for a large part anonymous – indeed, bidders could be agents for third parties or even buying-in their own goods to ensure that sales did not translate into loss. There remained powerful anxieties around the participation in such a spectacle of greed, financial dispersion and old money pitted against new money – these powerful currents threatened social order and could taint the sociability of the auction. Attendance at the auction always risked being sanctioned – and was easily satirized in print – especially for women in the audience, who largely had to participate with chaperon and who would rarely place bids themselves.

- 12. Sophie Vasset, ‘Pumping and Power: watering places and the money business’, in Murky Waters – British spas in eighteenth-century medicine and literature (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022), p. 212-246.

Auction houses as spaces merging commercial ethos and a burgeoning discourse of art and connoisseurship were instrumental in the creation of both ‘new canons of taste, and styles of sociability’ that Roy Porter identifies not just in epistemological breakthrough but in the very concrete building of sociable space that enabled for example ‘the marketing of new merchandise and cultural services’.13 Their sociability remained chaotic, and their modes of operating relied on frenzy and suspense which made them frequent targets of satire and censure, but they ‘spread a pretty general taste for pictures […] a taste which they not only excite but form’.14 This choregraphed spectacle of bidding wars framed by strict conditions of sales produced a discourse on the social values of cultural artefacts that was both publicly vetted and polyphonic.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Bayer, Thomas M. and Page, John R., The Development of the Art Market in England: Money as Muse, 1730–1900 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2011).

Berg, Maxine and Clifford, Helen, ‘Selling Consumption in the Eighteenth Century,’ Cultural and Social History(vol. 4, no 2, 2007), p. 145-170.

Cowan, Brian, The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

De Mulder, Alessandra, ‘London Calling from the Auction World: A Methodological Journey through Eighteenth-Century London Auction Advertisements’, Eighteenth-Century Studies (vol. 54, n° 4, 2021), p. 979-1004.

Dias, Rosie, ’”A World of Pictures”: Pall Mall and the Topography of Display, 1780–99’, in Miles Ogborn and Charles W. J. Withers, Georgian Geographies: Essays on Space, Place and Landscape in the Eighteenth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), p. 92–113.

Gibson-Wood, Carol, ‘Picture Consumption in London at the End of the Seventeenth Century’, The Art Bulletin (vol. 84, no 3, 2002), p. 491–500.

Lippincott, Louise, Selling Art in Georgian London: The Rise of Arthur Pond (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983).

Wall, Cynthia, ‘The English Auction: Narratives of Dismantlings’, Eighteenth-Century Studies (vol. 31, n° 1, 1997), p. 1-25.