Résumé

The betting book is the material expression of the sociable practice of betting, which became fashionable as part of the gambling culture of eighteenth-century Britain. More than a simple book used for recording the wagers made by a select company of clubmen or college fellows, the betting book provides a snapshot of a complex recreational practice that not only promoted social interaction and gentlemanly conviviality, but also challenged sociability and friendship. This specific object can be considered as the physical expression of the practice of betting and testifies both to the playful and conflictual form of sociable interactions.

Mots-clés

The betting book is the material expression of the sociable practice of betting, which became fashionable as part of the gambling culture of eighteenth-century Britain. More than a simple leisure accessory used for recording the wagers made by a select company of clubmen or college fellows, the betting book provides a snapshot of a complex recreational practice that not only promoted social interaction and gentlemanly conviviality, but also challenged the rules of sociability and friendship.

Available in London gentlemen’s clubs for their members, betting books provided the written proof of the commitment of both parties and therefore guaranteed the payment of the bet when it was resolved. Moreover, they testify to the conviviality of the members’ relationships and to their friendship beyond their diverging opinions. Above all, these betting books offer an accurate account of the variety of subjects of speculation, of the considerable amounts at stake and of the worth of this social and cultural practice, even though often considered as a futile and peculiar ritual.

The betting book had various functions as a significant cultural marker of a fashionable social practice and as an object of sociability. The bets recorded in such a specific archival source mirror both the diverse pastimes, tastes and fashions of eighteenth-century gentlemen and the evolution of their personal and collective values, interests, motives and anxieties. Moreover, it reveals that this leisure practice played a significant part in strategies of distinction through conspicuous consumption and sociable performance.

The betting book: an object at the heart of a specific sociable practice

Betting, itself part of the gambling culture, became prominent among members of eighteenth-century British society, essentially as a homosocial pastime. However, many feared that this practice would spread among the ladies, as expressed in the Connoisseur n°15:

They are at present very deep in cards and dice; […] I am inclined to suspect that our women of fashion will also learn to divert themselves with this polite practice of laying wagers. […] In a word, if this once becomes fashionable among the ladies, we shall soon see the time, when an allowance for bet-money will be stipulated in the Marriage Articles.1

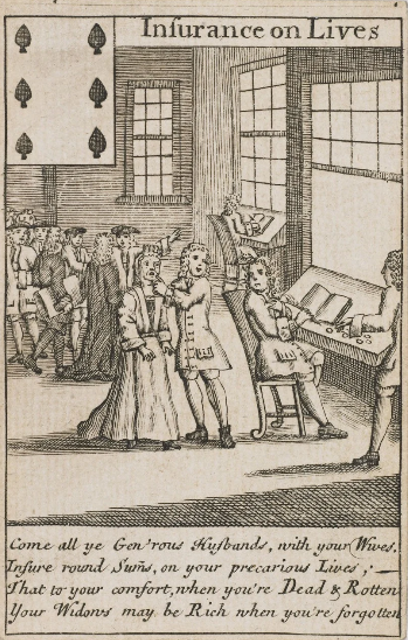

Such betting tradition takes its roots in the fashion for speculation that emerged at the end of the seventeenth century with the development of life insurance. ‘Life insurance was largely an urban phenomenon’2 and the growth of the London insurance market was associated with the expansion of English foreign trade in the second half of the seventeenth century. It was part of the remarkable period of financial activity which gave rise to the Bank of England, the Funded Debt and an embryonic stock exchange, culminating in the South Sea Bubble3 in 1720. As travel expanded, individual traveler’s insurance took on the form of a bet on their own survival; the Royal Exchange, incorporated in 1720, started to offer life insurance. Lloyd’s coffee-house was a place where seafaring captains could share shipping news and negotiate private contracts to cover the risk of shipwreck or violent conflict encountered on their trade routes. Maritime insurance thus expanded and captains were able to insure their own lives along with the safe return of their ships.

- 1. The Connoisseur, n° 15 (Thursday May 9, 1754)

- 2. Geoffrey Clark, ‘Life insurance in the society and culture of London, 1700-75’, Urban History, (vol. 24, n° 1, May 1997), p. 25.

- 3. The South Sea Bubble corresponds to the speculative fever on the South Sea company’s stock in 1720 and led to the ruin of many British investors. It became a political and financial scandal as a parliamentary investigation unearthed the corruption and bribery of several ministers.

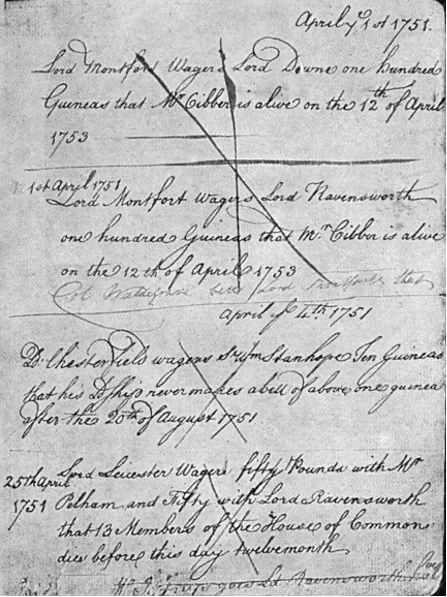

Part of this speculative drive, betting became an amusement as popular as card or dice games and was definitely one of the main occupations of the members of West End clubs in the second half of the eighteenth century: ‘London clubs [provided] the world of fashion with a central office for making wagers, and a registry for recording them.’4 Famous aristocratic gambling clubs started to keep betting books for members to record their wagers. In such socially exclusive institutions, betting was always for money and the stakes could be very high. White’s and Brooks’s respective betting books constitute major sources for the historian, as testimonies of club life. White’sbetting book, dated 1743, was integrally published in the second volume of the official historian of the club Algernon Bourke’s History of White’s (1892). Brooks’s ‘Betts’ book’, held at the London Metropolitan Archives, is also a rich source, with its first bet recorded in 1771.5

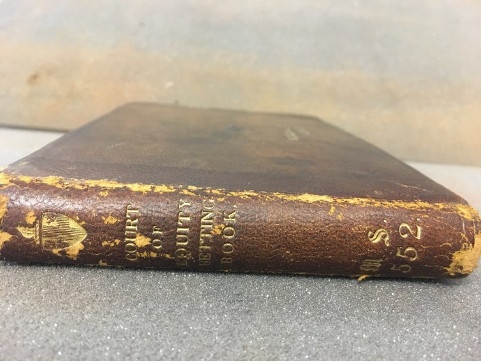

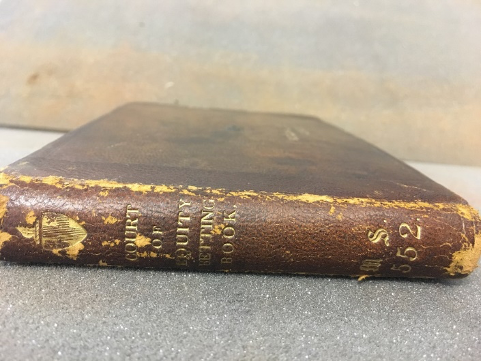

Some members of minor eighteenth-century clubs met in taverns to indulge in betting and drinking. For example, the ‘Board of Brothers’, afterwards the ‘Board of Loyal Brotherhood’, was a Tory-Jacobite drinking club founded in 1709 by Henry Somerset, 2nd Duke of Beaufort.6 The first bets recorded date back to 1735, then the club kept a dedicated betting book to record their members’ wagers from 1771. However, they did not bet for money but for wine, the usual stake being one gallon, even if the first wagers mentioned ‘twelve flasks’ or ‘six bottles’. The betting book of another society called the Court of Equity, which met at the Cheshire Cheese, Wine Office Court, in Fleet Street, reveals that its members never betted any money but usually ‘one bottle of wine’: significantly enough, the gain of the bet was often shared between the members present, emphasizing the convivial nature of such a practice.7

In a different but still homosocial context, betting books also became a common feature of collegiate life in Oxford or Cambridge. They recorded all the wagers made between Fellows in the Senior Common Rooms. The Senior Common Room (SRC) served as a base for the college’s senior staff members and students, offering to them a genuine collegiate atmosphere of conviviality, intellectual stimulus, networking and recreational opportunities. Fellows gathered to drink their wine, smoke their pipes, read their newspapers, play cards, and converse in seclusion from their pupils and servants, just like in a gentleman’s club. Lincoln’s SRC was one of the earliest established in Oxford and still possesses a betting book that starts in 1809, even if the practice was much older. As for Corpus Christi, its SCR kept a betting book from 1795 to 1810, while University college’s also recorded its bets from 1794 to 1810. Exeter College’s first betting book runs from 1812 until 1837. Betting was a way of introducing uncertainty into the predictable routine of common room life, providing entertainment and laughter, and wine for more partakers than the winners, if the bets had been laid in a decent number of bottles of port, claret or burgundy.

- 4. G. O. Trevelyan, The Early History of Charles James Fox (London: Longmans, Green & co, 1881), p. 479.

- 5. ‘Betts Book 1778’ is inscribed on the cover of its brown leather-bound book. Originally Almack’s, officially took the name of Brooks’s in 1778. ‘Brooks’s Club, Betting book’, LMA, Mss Acc/2371/BC/04/073.

- 6. This political faction met during parliamentary sessions, usually weekly, until 1763, and continued in a modified form after that date. ‘Honourable Board of Loyal Brotherhood. Record of bets made’, LMA, A/BLB/002 (Apr. 1771 - May 1833).

- 7. ‘Court of Equity Club, Betting book’, LMA CLC/059/MS00552 (1768-1772).

The betting book and the nature of bets

A betting book is usually a leather-bound and hand-written manuscript, in which are recorded all the wagers laid by a select community of bettors. Brooks’s betting book is described as ‘one book, the size of an ordinary, thick notebook, on rough paper with gilt edges.’8 A bet always has the same format and wording: A bets/wagers/lays B a certain amount of money or quantity of wine that an event will or will not occur within a certain timeframe. Bets recorded in betting books are designed to be shared and verified, to keep track of the wagers. The majority of Brooks’s bets are not signed or initialed, nor is their settlement recorded, as who actually won did not matter. Sometimes, as in other betting books, the bet bears the mention ‘paid’ or is simply crossed out. Short-term wagers were probably not written down since the bets were only open contests for a few hours. The book was useful for the longer-term wagers which might result in disputes due to convenient memory loss or denial that a wager ever occurred.

Bets were characterized by the variety of their topics. The slightest details of everyday life could lead to tense gambling situations as they could, at any moment, become the object of a bet, as suggested by the Connoisseur: ‘The gentlemen who now frequent this place [White’s], profess a kind of universal scepticism; and as they look upon everything as dubious, put the issue upon a wager. There is nothing, however trivial or ridiculous, which is not capable of producing a bet.’ If bets reflected the character of a profoundly interesting society, they can sometimes be perceived as a social satire.

The fashionable practice of speculating on demographics coincided with both the progress in medicine and hygiene and with the general increasing craze for life insurance. A significant proportion of the bets made by club members were either on the life expectancy of the men and women of the time, the fertility of ladies or on the probability of a marriage. The early bets recorded in White’s betting book mark this trend and mainly consist in pitting lives against one another.

- 8. G. S. Street, ‘The Betting Book at Brooks's’, The North American Review (vol. 173, n° 536, July 1901), p. 46.

Octr. ye 5, 1743.

Ld. Lincoln bets Ld. Winchelsea One hundred Guineas to fifty guineas, that the Duchess Dowager of Marlborough does not survive the Duchess Dowager of Cleveland.9

One of the most famous bets of the history of gentlemen’s clubs was reported in a letter from Horace Walpole to his friend Horace Mann:

They have put in the papers a good story made on White’s: a man dropped dead at the door, was carried in; the club immediately made bets whether he was dead or not, and when they were going to bleed him, the wagerers for his death interposed, and said it would affect the fairness of the bet.10

The excessive character of this bet testifies to the absurdity of some wagers and of the speculative frenzy that had seized London high society, often relegating morals, or simply good sense, to the second level.

Most of the bets recorded in aristocratic clubs’ betting books dealt with politics, obviously because those gamblers happened to govern England. Political events, either domestic or diplomatic or military, occupy a significant position in betting books:

March 21st 1755.

Ld. Sussex bets Mr. Chas. Boone ten guineas, that there is no Declaration of War before this day twelve months between England and France. (Bourke 34)

Feb. 4 1783.

Lord Derby bets Genl. Smith 10 Guineas that the present Parliament is dissolved on or before this Day Twelve months. (Brooks’s 87)

- 9. Algernon Bourke, The History of White's with the Betting Book from 1743 to 1878 and a List of Members from 1736 to 1892 (London: Waterloo & sons ltd., 1892) vol. 2, p. 1.

- 10. Letter to Mann (1 Sept. 1750), Horace Walpole, Correspondence, Vol. 20, p. 185. This anecdote was originally made public the week in the London Evening Post, n° 3564 (25-28 Aug. 1750). Twelve years later, Casanova de Seignalt referred to this same extravagant story in his memoirs: Mémoires de J. Casanova de Seignalt (Paris: Garnier frères, 1880) vol. 6, p. 461.

Times of political intrigue, such as elections, caused a spike in the volume of bets, as did periods of great war.For instance, the American war of Independence was the object of multiple bets.11 The same diversity of bets can be observed in minor tavern clubs. In the betting books of the Board of Loyal Brotherhood or the Court of Equity, wagers ran from speculation on the weight of a person or of a goose to predictions on the drawing of the lottery or on potential Parliamentary elections or legislation.

College betting books contained bets on the matrimonial chances of the fellows as well as bets on political matters. In Exeter’s betting book for example, the bets touch on politics as well as College life, reflecting the political and military concerns of England and Europe. These great events filtered into the common room via the daily papers now purchased through common room subscriptions, to provide food for conversation and subjects for wagers. If many bets dealt with the situation in France and the outcome of the war with Napoleon, as well as with domestic politics, various sporting bets can also be found usually depending on the sporting traditions of Oxford or Cambridge colleges.

In the second half of the eighteenth-century, dedicated sporting clubs developed in England bringing together members who had a passion for a particular sport – and sometimes also a love of the gambling such sport encouraged. Betting almost immediately became the raison d’être of racing. The Jockey Club was founded in 1750, even if mentions of Jockey Club meetings were found in newspapers as early as 1729. Around 1800, some horse owners were taking or laying odds on a number of horses in a race to minimize potential losses or maximize their profits, recording bets in their betting books, to be settled at a later date. However, this practice was often denounced by satirists who criticized the excessive gambling and debauchery of the noblemen who indulged in the pleasures of the turf.

- 11. At Brooks’s, the first bet on that topic was made on December 13th, 1774, when ‘Ld. Bolingbroke betts Mr. Fox 150, to 50, that the Tea Act is not repealed this Session.’

The social and cultural function of the betting book

The betting book offers a precious testimony of club life providing a snapshot of a choice community of gentlemen. Moreover, its content informs us about the society of the time, especially about the social behaviours, manners and fashions of the elite. Not only was betting a form of entertainment and commerce, through its enjoyable and sociable nature, but it also stood as a social performance, a highly visible activity promoting distinction and social prestige. Somehow, the betting book acted more as a ceremonial piece, rather than a bureaucratic aid. Enshrining one’s wager in the book for all to read was definitely part of the culture of conspicuous consumption. A betting book was placed on display for all club members to view, and thus acted as a ‘semi-official receptacle of gossip.’12 Amy Milne-Smith, a specialist of the London Victorian clubland, considers male gossip as a prominent practice in gentlemen’s clubs and confirms that the betting book inevitably fuelled conversation and debate as men discussed the latest news and rumours of the day.

Betting was a shared sociable experience, a convivial practice that could also raise tensions and challenge friendships. The betting book itself had the power to both gather and oppose men and opinions, yet always in an entertaining and regulated manner. Despite its potential for causing individual disputes, betting reinforced links between members and served to redistribute modest sums of wealth in a random way, underlining equality and unity. The rules of etiquette and the mastery of sociable pastimes were integral to the conduct manuals of the time, as part of gentlemanly culture. The gentleman’s prime motivation was his desire for social approval, hence the essential value of honour, which constituted the very essence of his reputation in the eyes of his peers.13 Backing one's judgements and opinions with money dramatized status and provided a means of settling disputes and arguments without violence. Most of the time, when two gentlemen disagreed on an issue, they automatically resorted to a bet, but when the honour of one of them was at stake, it would often end up in a duel.14 If high stakes persisted until the late 1780s, betting suffered from a decline in popularity among aristocratic circles in the first half of the nineteenth century. The 1774 Life Insurance Act15 may have had an impact on the betting habits, as we can observe the deceleration of prime risk taking in elite clubs in the following decades. By the 1810s betting books reveal that the majority of bets were for low sums of money and mostly about politics, even if their number remained high.

The betting book as the physical expression of the practice of betting testifies both to the playful and conflictual form of social interactions. Such an object, when it survived, enables us to draw the contours of a community of betters, forming a sub-category of the community of club members, therefore paradoxically symbolising, one the one hand, togetherness and conviviality, on the other hand, exclusiveness and antagonism. While the betting book can be considered as an ideal instrument of social and cultural identification and prestige, it also perfectly encapsulates the tensions between the expectations of gentlemanly politeness and aristocratic honour and the potential dangers of addictive gaming, excessive gossip, and other types of unruly behaviour.

- 12. Amy Milne-Smith, ‘Club Talk: Gossip, Masculinity and Oral Communities in Late Nineteenth-Century London.’ Gender & History (vol 21, no. 1, April 2009), p. 93.

- 13. ‘Honour is not in his hand who is honoured but in the hearts and opinions of other men’, John Cleland, The Institution of a Young Nobleman [1607], quoted in M. James, ‘English Politics and the Concept of Honour’, Past and Present (sup. III, 1978), p. 4.

- 14. ‘Our ancestors […] regarded a duel as the natural issue of a quarrel, and a bet as the most authoritative solution of an argument’ (Trevelyan, p. 478).

- 15. Also known as the Gambling Act 1774 (14 Geo. 3 c. 48), it prevented the abuse of the life insurance system to evade gambling laws.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Ashton, John, The History of Gambling in England (London: Duckworth & Co, 1898).

Capdeville, Valérie, L’ Age d’or des clubs londoniens (1730-1784) (Paris : Éditions Champion, 2008).

Clark, Geoffrey, Betting on Lives: The Culture of Life Insurance in England, 1695-1775 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999).

Huggins, Mike, ‘The Secret World of Wagering’, in Mike Huggins (ed.), Horse Racing and British Society in the Long Eighteenth Century (Boydell & Brewer, 2018), p. 79-121.

Midgley, Graham, University Life in Eighteenth-Century Oxford (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996).

Ziegler, Philip and Seward, Desmond (eds.), Brooks’s: A Social History (London: Constable, 1991).

In the DIGIT.EN.S Anthology

Daniel Defoe on races (1724)