Résumé

At London’s Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, sociability practices were realized, queried and transformed by actors and audiences. This entry describes the theatre’s physical spaces, then considers modes of sociability within the theatre, from normative theatre-going practices to disruptions such as riots. The name ‘Drury Lane’ also became an important cultural marker of an aspirational, genteel, and performative literary sociability outside the institution, in theatrical discourse across various media from newspapers to novels. Drury Lane Theatre was a crucible for the formation of social behaviour and the examination of sociability’s performative nature.

Mots-clés

Spaces

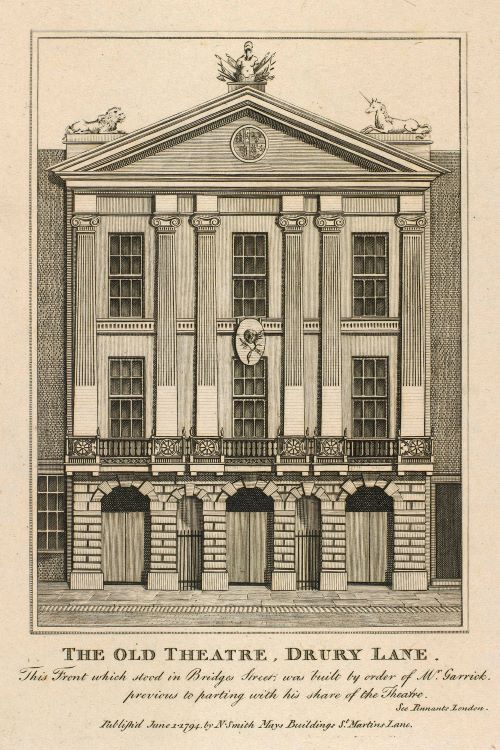

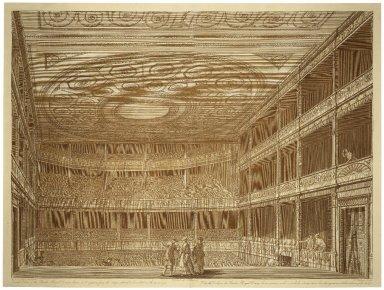

The name Theatre Royal, Drury Lane refers to a succession of four buildings in the area bordered by Drury Lane, Russell Street, and Bridges (later Catherine) Street in London; each rose phoenix-like from the ashes of the theatre before it. The first Theatre Royal (sometimes referred to as the Bridges Street Theatre) was built by Sir Thomas Killigrew; it opened in 1663 and was destroyed by fire in 1672. The second, attributed to Sir Christopher Wren, opened in 1674. This building, with its dignified columns, was the one familiar to most eighteenth-century audiences; it underwent various renovations, including an airy neo-classical redesign by Robert Adam in 1775, before it too burned down in 1791. Its replacement, designed by Henry Holland, opened in 1794 and burned in 1809.1

- 1. For contemporary prints that give visual evidence of Drury Lane Theatre’s appearance and imagined reconstructions rendered in line-drawings, see Richard Leacroft, The Development of the English Playhouse (London: Eyre Methuen, 1973). For space’s impact on staging, see Edward A. Langhans, ‘The Post-1660 Theatres as Performance Spaces’, in Susan J. Owen (ed.), A Companion to Restoration Drama (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), pp. 3-18.

The last theatre on the site, designed by Benjamin Wyatt, opened in 1812; most recently refurbished in 2021, it remains a working theatre today.2

![Rawle, S., ‘New Theatre Royal Drury Lane, B. Wyatt Esqr., architect [graphic] / engraved by S. Rawle ; L. Francis delt’, Folger Shakespeare Library, 30373, late 18th to mid-19th century, https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/61s5m6](https://www.digitens.org/sites/default/files/inline-images/DL%20garde%201_0.jpg)

Speaking shorthand of ‘Drury Lane’ as scholars sometimes do is revealing: rather than referring only to a particular theatre or site, ‘Drury Lane’ signified certain kinds of theatrical sociability, not all of which involved physical presence in the theatre. Nonetheless, the four Theatres Royal in Drury Lane shaped these modes of sociability, and it is with their physical spaces—so far as they can be determined—that we begin.

- 2. To see the present-day theatre’s listings, go to https://drurylanetheatre.com.

Actors played downstage of the scenic space on the thrust or forestage portion of Drury Lane’s raked stage, where their proximity to the audience enabled sympathetic transmission of the passions and nimble verbal exchanges. Actor and theatre manager Colley Cibber felt a loss when the ‘original Form’ of Wren’s theatre was altered. Before the stage was shortened and stage-boxes added, Cibber writes, actors were at least ten feet closer to the audience, who could see ‘the minutest Motion of a Feature’; hear a voice ‘scarce rais’d about the Tone of a Whisper, either in Tenderness, Resignation, innocent Distress, or Jealousy, supress’d’; and view the scenes and costumes to greater effect.3

- 3. Colley Cibber, An Apology for the Life of Mr. Colley Cibber, Comedian, and Late Patentee of the Theatre-Royal. With an Historical View of the Stage During His Own Time (London: John Watts, 1740), p. 241.

Pleasure at well-wrought artifice, not mimetic realism, was the aim from the very first Theatre Royal, where audiences delighted in hearing the prompter’s whistle as scenes painted on four or more sets of wings and shutters slid open and closed before their eyes without any intervening curtain drop.4 An evening’s entertainment might include a five-act play and a shorter afterpiece, each with a prologue and epilogue, as well as dances, music, acrobatic or other entertainments between the acts or the main and afterpiece.

- 4. Edward A. Langhans, ‘The Theatre’, in Deborah Payne Fisk (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to English Restoration Theatre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 9.

As audience capacity grew from approximately 700 in the first Theatre Royal to around 2000 spectators in the second, 3,600 in the third, and 2,200 in the fourth theatre,5 each successive alteration of Drury Lane’s theatrical space was mourned as a loss to communication with audiences for profit’s sake. The Oracle’s theatre critic remarked of a 1798 production of The Stranger that actress Sarah Siddons spoke in such a refined manner that ‘in the large Theatre of Drury-Lane, she was for the most part inaudible to the whole audience, who could only collect from deep tones […] her action and gesture, what her expression meant.’6 Increasingly large audiences, however, still found much to enjoy in the spectacle the expanded theatre afforded. At the third theatre’s opening, the Whitehall Evening Post approvingly noted the audience’s splendour matched the new theatre’s grandeur during the showing of Macbeth, which featured such spectacles as Hecate’s spirit descending on a cloud by means of a machine; a Fuseli-inspired crowd of evil spirits writhing with serpents around the witches’ cauldron; a shocking amount of thunder; as well as the novelty of John Philip Kemble as Macbeth resting his eye upon the air rather than upon an actor portraying Banquo’s ghost.7

At the risk of oversimplifying, one might say that over the century Drury Lane Theatre transformed from an intimate public space in which audience and actors engaged in the reciprocal cut and thrust of witty repartee to a more capacious space with increasing reliance upon spectacle to summon collective passions such as awe, wonder and sympathy.

Drury Lane’s Audiences

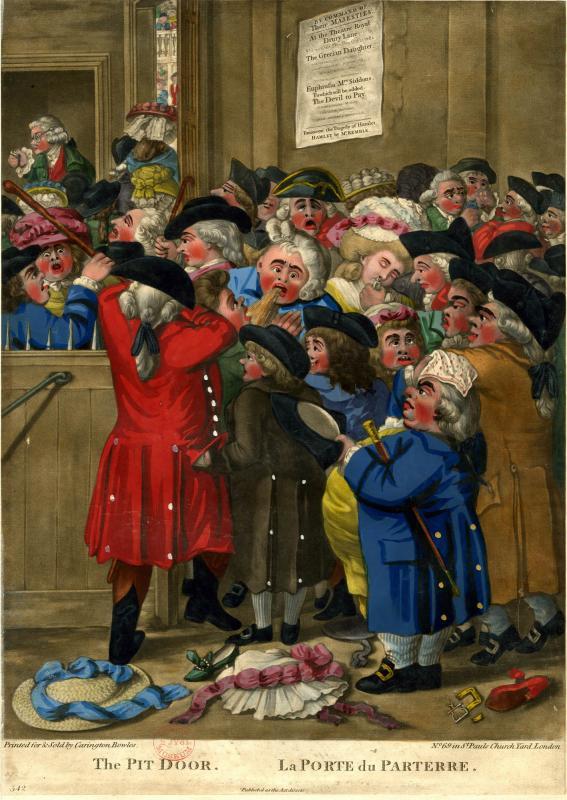

Differently priced seating zones within Drury Lane Theatre typically correlated with persons of a certain social class, and thus each space embodied and generated different social expectations.8 In the most expensive seats, the boxes, sat the gentry, aristocrats, and royalty, richly dressed to see and be seen. Royalty might ‘command’ certain repertoire, and their advertised presence at a performance drew audiences, too. The gallery was frequented by the middling sort and tradesmen. Cheap seats in the upper gallery hosted servants, soldiers, and sailors, who rained down loud opinions on those below; while connoisseurs of drama, playwrights, and critics could be found upon the pit’s benches near the stage, the better to observe stage-action. In the Duke of Buckingham’s play, The Rehearsal, which premiered at Drury Lane in 1671, the phrase ‘pit, box and gallery’ metamorphosed into a verb meaning to make a broad or multi-pronged appeal to all the playhouse’s social constituencies: ‘it shall Read, and Write, and Act, and Plot, and Shew, Ay, and Pit, Box, and Gallery, I Gad, with any Play in Europe,’ the playwright character Bayes boasts of his new drama.9 Lighting within the playhouse meant that audience members were as visible to one another as the performers on stage were to them; the audience’s gaze often fastened upon diverse human dramas inside Drury Lane rather than at those represented onstage.

- 8. Judith Milhous summarizes these ticketing zones and their differential pricing thus: from 1660 to 1700, ticket prices ran 4s (boxes), 2s 6d (pit), 1s 6d (first gallery), 1s (upper gallery). By 1746-7, common prices were 5s, 3s, 2s, 1s; and in the 1780-90s, tickets ran 6s, 3s 6d, and 2s. For new productions ticket prices were raised, either throughout the theatre (described as “advanced prices”) or in part (“pit and boxes laid together”). Judith Milhous, ‘Company Management’, in Robert D. Hume (ed.), The London Theatre World, 1660-1800 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1980), pp. 17-18.

- 9. George Villiers Buckingham, The Rehearsal, as It Is Now Acted at the Theatre-Royal, 7th ed. (London: Richard Wellington et al, 1701), p. 6.

Diaries and journals yield insights into the ways that individuals navigated Drury Lane Theatre’s social milieu. Samuel Pepys, a frequent visitor to the first Theatre Royal, recorded a visit on 8 December 1666 that illustrates a nexus of social pleasures and anxieties:

There [I] did see a good part of ‘The English Monsieur,’ which is a mighty pretty play, very witty and pleasant. And the women do very well; but, above all, little Nelly; that I am mightily pleased with the play, and much with the House, more than ever I expected, the women doing better than ever I expected, and very fine women.10

For Pepys, playhouse pleasures included the novelty of seeing actresses playing women’s roles (he also admired the skill of Edward Kynaston, one of the last actors to play women’s roles in the Renaissance tradition); familiarity with actresses like Nell Gwynn, mentioned here, whom he enjoyed visiting backstage in the tiring-rooms; and not only critiquing the play’s dramatic merit, but observing other audience members. Not everyone was so pleased. The period’s robust anti-theatrical literature, including Jeremy Collier’s A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage (1698), considered theatrical pleasure suspect precisely because of its affective power and ability to influence social formation: ‘Nothing has gone farther in Debauching the Age than the Stage Poets, and Play-House,’ wrote Collier; theatre ‘strikes at the Root of Principle, draws off the Inclinations from Virtue, and spoils good Education: ‘Tis the most effectual means to baffle the Force of Discipline, to emasculate peoples Spirits, and Debauch their Manners.’11 Restoration-era playgoing occasioned self-monitoring; Pepys assessed himself a monetary forfeit (given to charity) for what he viewed as excessive, addictive pleasure in the theatre.

- 10. For further analysis of Pepys’s playgoing, see Deborah C. Payne, ‘Theatrical Spectatorship in Pepys’s Diary’, The Review of English Studies (vol. 66, n° 273, 2015), pp. 87–105.

- 11. Jeremy Collier, A Short View of the Immorality, and Profaneness of the English Stage (London: S. Keble, R. Sare, and H. Hindmarsh, 1698), A2, p. 287.

Later in the century, the writer Frances Burney described visiting Drury Lane to see a favoured actor in a role for which he was famous: David Garrick as Richard III. Garrick, who purchased half of a royal theatrical patent with James Lacey in 1747, was synonymous with Drury Lane, as he co-managed, acted, and wrote for that theatre until 1776. Burney and her sisters ‘had always longed to see him [Garrick] in all his great characters,’ a viewing practice that speaks to theatrical celebrity’s growing import. Burney was shaken at seeing her family’s friend transformed into a villain and moved by communal approbation of his performance: ‘he seemed so truly the monster he performed, that I felt myself glow with indignation every time I saw him. The Applause he met with exceeds all belief […] I thought, at the End, they would have torn the House down: Our seats shook under us.’12 Burney’s account shows how the ‘affective sensibility of the collective becomes desired in itself’ in a ‘shared sense of the power of numbers.’13

Drury Lane’s audiences were well aware of their collective power and far from passive spectators. Punctuations of applause were not limited to the end of an act or a play; audiences clapped and shouted their admiration of a well-turned speech, a fine posture or attitude, a song or prologue, and sometimes demanded that the performers repeat it. At the height of Jacobite tensions in 1745, Drury Lane’s audience was ‘agreeably surprized by the Gentlemen belonging to that House performing the Anthem of God save our noble King,’ and demonstrated loyalty to the Crown by encoring the anthem with ‘repeated Huzzas.’14 Audience participation could reshape a text’s emotional and artistic affect, breaking the entertainment into new divisions with vociferous affirmations, or loud catcalls and hisses. When, on 18 October 1751, the theatre’s prompter Richard Cross noted that the audience began making ‘a great noise’ and throwing horse beans at the actors for blundering lines, the curtain was brought down and an actor apologized: ‘Gentlemen I am very sorry this Accident shou’d happen, but before this little piece is perform’d again, I’ll take care to see it so well practis’d that no Mistake can happen for ye future. Great Applause.—The play was hiss’d again at the End.’15

It was not always possible to mollify an unhappy audience with printed or performed apologies from Drury Lane’s players or managers: audiences opposed such appeals to social standards of polite behaviour with noisy assemblages known as claques to support, and cabals to damn an author, play, actor, or theatre, creating disruptions that could escalate into destructive rioting. In the spring of 1712, Ambrose Philips felt the best actress for the lead in his tragedy, The Distrest Mother, was Anne Oldfield; the actress he spurned, Jane Rogers, retaliated and ‘raised a Posse of Profligates, fond of Tumult and Riot, who made such a Commotion in the House, that the Court hearing of it sent four of the Royal Messengers, and a strong Guard, to suppress all Disorders.’16

- 16. William Egerton, Faithful Memoirs of the Life, Amours and Performances, of That Justly Celebrated, and Most Eminent Actress of Her Time, Mrs. Anne Oldfield Interspersed with Several Other Dramatical Memoirs (London: Edmund Curll, 1731), pp. 31-32.

The sociable occasion of attending a play at Drury Lane Theatre was always tempered with the knowledge that violence and commotion were possible—a potential manifested in the spiked iron railings that separated the pit audience from the orchestra and stage. Other notable riots included the 1755 Chinese Festival riots, when xenophobic audiences protested the presence of so-called ‘French dancers’, mirroring Britain’s political tensions with France; and the Half-Price riots of 1763, when audiences smashed up both Drury Lane and Covent Garden theatres to protest what they perceived of as a change to ticketing policy and prices.17

- 17. The actor was Mr. Woodward. Richard Cross, The Cross-Hopkins Theatre Diaries, 12 vols (Folger Shakespeare Library), vol 1-13.

Audiences’ sense that they were entitled to be pleased within the theatre space is perhaps a legacy of earlier eras’ conception of actors as servants, though actors now sought public and commercial rather than aristocratic patronage, and audiences invoked economic and nationalist sentiments to defend their actions. Whereas in 1706, Jeremy Collier could write, ‘whether the Trade of an Actor be a lawful Trade or not, I’m sure ‘tis not a Trade of good Reputation,’18 by the late 1700s, actors like Garrick and Siddons were able to mobilize respectable domestic ideology and financial success as part of their celebrity. Iterative contact with genteel society within Drury Lane Theatre and increased media representation of the theatre transmuted the reputations of individual actors and the acting profession from questionable to admirable.

- 18. Jeremy Collier, A Letter to a Lady Concerning the New Play House (London: Joseph Downing, 1706), p. 14.

Social Work & Workers at Drury Lane

The theatre was frequented by all social ranks, but its calendar reflected the movements of London’s elite. Drury Lane’s theatrical season began in late September or October as its aristocratic and genteel patrons returned from country estates for the opening of Parliament and other society events. The theatrical season concluded in May or June with a month or two of benefit performances. For each benefit, an individual actor or group of actors or other playhouse professionals (such as dancers, musicians, or prompters) would choose the repertoire, sell the tickets, entreat their friends to fill the house, and receive the house takings, usually after expenses such as the cost of lighting the theatre were deducted. Drury Lane’s most prominent actors and actresses negotiated the most profitable nights early in the benefit season whilst London’s ton was still in town, and appeared in roles for which they were known or to which they wanted to stake a claim. Benefits, no less than salary structures and name-placement in playbills, reveal actors’ and writers’ professional hierarchies and the theatre’s patronage networks.

Some plays in Drury Lane’s repertoire openly performed social and political work. Performances of Nicholas Rowe’s play Tamerlane in November were tied to historic dates to remind theatre patrons of elements of their national identity.19 Britain’s recovery after the loss of her American colonies likewise ‘entailed intense cultural work that fundamentally realigned identity categories and social dispositions,’20 in part through a reimagined repertoire. George Lillo’s domestic tragedy, The London Merchant, was performed on apprentices’ holidays to encourage City apprentices to be dutiful and loyal to their masters, thereby reinforcing social hierarchies. December brought forth a charitable performance, often to benefit one of London’s lying-In or maternity hospitals. Occasionally, a performance might provide disaster relief, such as that given victims of a fire in Cornhill in March 1748. Though heavily advertised to make the theatre’s acts of public charity conspicuous, charity performances were usually limited to two per season, so as not to damage the theatre’s financial health.21 Following Covent Garden Theatre’s lead in 1765, in 1766 Drury Lane also began staging an annual benefit for a fund for actors who had left the profession due to age or illness. The Theatrical Fund was a sign of the increasing professionalization of acting, and audiences might demonstrate their charity simply by purchasing a ticket. The first time Sarah Siddons acted in Drury Lane’s Theatrical Fund benefit in May 1783 ‘she raised £292, a sum that evinces the importance of star power for fund-raising: the year before, without a star of her magnitude, the fund raised only £152 8s.’22 Under these auspices, attending Drury Lane Theatre might be considered no mere entertainment, but an act of public good or an expression of patriotic fervour.

- 19. J. Douglas Canfield observes, ‘Tamerlane is a thinly veiled, idealized portrait of William III and Bajazet a thinly veiled, demonized portrait of Louis XIV’ and the play was acted on the anniversary of William III’s birth (November 4) and his arrival in England (November 5), reifying England’s image of itself as a Protestant nation. See J. Douglas Canfield (ed.), The Broadview Anthology of Restoration & Early Eighteenth-Century Drama (Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2001), p. 38.

- 20. Daniel O’Quinn, Corrosive Solace: Theater, Affect, and the Realignment of the Repertoire, 1780-1800 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022), p. 2.

- 21. For more on Drury Lane’s charity performances under Garrick’s management, see Leslie Ritchie, David Garrick and the Mediation of Celebrity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 128-136.

- 22. Danielle Spratt, ‘’Genius Thus Munificently Employed!!!’: Philanthropy and Celebrity in the Theaters of Garrick and Siddons’, Eighteenth-Century Life (vol. 37, n°3, 2013), p. 78.

The Theatre Royal in Drury Lane was the site of other transactional exchanges besides those occurring between audience and actors: licensed vendors sold fruit inside the theatre; printers hawked books of the play in the theatre’s passageways; and prostitutes sought custom in the pit or galleries. In addition to these highly visible unsalaried workers and the theatre’s offstage staff (boxkeepers, scenemen, dressers, and others), a vast network of unseen jobbing labourers and skilled tradespeople manufactured the stuff that supported the theatre’s glittering illusions. Surviving theatre account books and financial documents show Drury Lane Theatre’s immense socio-economic impact: milliners, linen-drapers, tallow-chandlers, coal-men, glovers, mercers, shoemakers, wig and peruke-makers, lacemen, and printers are but a few of the tradespeople named in the accounts as employed in the theatre’s service.

In some ways, Drury Lane was radically progressive: women’s considerable presence and influence in the theatrical workforce represents a ‘major social innovation in the area of gender equality in the workplace’;23 similarly, though the theatre’s calendar and records of audience response skew towards elite society, financial records offer a salutary reminder that Drury Lane’s audiences and artisans were socially heterogeneous.

- 23. David Worrall, Celebrity, Performance, Reception: British Georgian Theatre as Social Assemblage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 235.

Associative Connections: ‘Drury Lane’

The name ‘Drury Lane’ became an important cultural marker of an aspirational, genteel, performative literary sociability outside the institution, as one may see by examining theatrical discourse across various media. Some associative connections with ‘Drury Lane’ were period-specific, while others accrued weight and resonance over the long eighteenth century.

From the first, when it housed an acting company operating under one of only two theatrical letters-patent granted by King Charles II to license the production of entertainment in London, Drury Lane was associated with drama that was officially sanctioned. Though the patents were legal documents of control held by patentees (usually the theatre’s managers), not by the theatres per se, by association Drury Lane became known as a ‘patent theatre’; thus, it operated under both the commercial protection of a legally limited theatre market and the halo of its prestigious association with the Crown.

The public sense of Drury Lane as an official site of culture intensified following the Licensing Act of 1737. New and revised plays had to be examined and licensed by the Lord Chamberlain’s office, which under the patents’ terms had the responsibility to censor texts judged blasphemous, indecent, slanderous or seditious. Though this power was not often exercised, it nonetheless conditioned cultural expectations that the playhouse’s entertainments would be consonant with national interests and composed or revised in line with current social mores.

David Garrick’s persistent identification of Drury Lane Theatre with Shakespearean drama (despite clear similarities in its repertoire to the pantomimes and other spectacles offered at its rival patent theatre, Covent Garden)24 resulted in this theatre’s association with high culture of national significance.

![‘Theatre Royal, Drury-Lane. This present Tuesday, September 18, 1798, Their Majesties Servants will act the tragedy called Macbeth : with the original musick of Matthew Locke. And accompaniments by Dr.Arne, and Mr. Linley … Mr. Aickin … Mr. C. Kemble’, Yale University Library, Lewis Walpole Library, 767 P69BD841798, [1798], https://hdl.handle.net/10079/digcoll/2782263](https://www.digitens.org/sites/default/files/inline-images/Capture%20d%E2%80%99%C3%A9cran%202022-09-11%20%C3%A0%2022.32.59_0.png)

- 24. Robert D. Hume, ‘John Rich as Manager and Entrepreneur’, in Jeremy Barlow and Berta Joncus (eds), The Stage’s Glory: John Rich (1692-1761) (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2011), pp. 46-48.

During Whiggish Member of Parliament Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s tenure as proprietor and manager (1776-1809), audiences came to expect overtly political content and to consider Drury Lane as a site where state and stage overlapped, creating a space for engaging with Opposition ideology.25

- 25. See David Francis Taylor, Theatres of Opposition Empire, Revolution, and Richard Brinsley Sheridan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

London’s public sphere was saturated with print notices of Drury Lane’s offerings: billstickers posted bills of the play around the city, and notices of forthcoming performances appeared daily in newspapers such as the Public Advertiser. Newspapers increasingly carried ‘Theatrical Intelligence,’ reviews, and correspondence which cultivated audiences’ tastes, modelling different occasions for and modes of critical intervention and preparing spectators for a night at the theatre.26 For example, in the General Evening Post of 22-25 February 1772, a correspondent objects that two actresses in The Provok’d Husband spoke with polished London accents ‘as if they had conversed with none but the politest circles of the bon ton’ though they ought to have spoken broad Yorkshire dialect like their male counterparts, because the actresses ‘ridiculously imagine that the mere circumstance of their being women, is to preserve them securely from the reach of verbal barbarity.’ The writer clearly does not cherish rural accents but finds the actresses’ failure to employ them properly to be a worse sin against social representation than adhering to gender expectations in performance. Pamphlets (single-topic booklets around thirty pages in length) offered theatrical partisans opportunity to pursue extended paper wars of theatrical criticism. Following the publication of Colley Cibber’s witty Apology (1740), the market for dramatic histories, actors’ biographies, memoirs, and autobiographies—genres frequently intermingled—expanded. Novels such as Frances Burney’s Evelina (1778) and Tobias Smollett’s The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771) featured Drury Lane as a setting revelatory of characters’ social identities; Tabitha Bramble’s cultural pretensions are exposed when she demands that actor James Quin repeat his famed ‘Ghost of Gimlet’ lines about ‘quails upon the frightful porcosine,’ for example.27

- 26. The definitive survey of theatrical criticism in the period remains that by Charles Harold Gray, Theatrical Criticism in London to 1795 (New York: Benjamin Blom, 1931, 1964).

- 27. See Frances Burney, Evelina, or A Young Lady’s Entrance into the World, 3 vols (London: T. Lowndes, 1778), vol 1, p. 28; for Tabitha Bramble’s mangled Hamlet reference, see Tobias Smollett, The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, 3 vols (London: W. Johnston, 1771), vol 1, pp. 107-108.

The ‘Drury Lane’ name on print and other material products offered an invitation not just to attend or read about that theatre, but to engage with theatricality by performing oneself. Coffeehouses near Drury Lane offered spaces for discussing and forming public opinion on theatrical matters. Coffeehouse patrons could consult newspaper reviews, read pamphlets or playbooks, trade theatrical anecdotes, and converse with fellow theatre afficionados and practitioners, including Drury Lane’s actors and managers. Books of jests and bon mots, their titles touting the theatre as a site of wit’s provenance, encouraged the public to imitate theatrical celebrities.28 ‘Spouting companions’ catered to amateur actors belonging to tavern-based spouting clubs who desired to reproduce actors’ famous speeches and attitudes, often with the directive ‘as performed at Drury Lane Theatre’. The “Prologue on Prologues” on the first page of a spouting companion exemplifies this practice: 'Written by Mr. Garrick, and spoken by Mr. King, at the Theatre-Royal in Drury Lane.'29 Amateur musicians delighted in the ability to purchase, sing, and play music from the theatre’s productions.30 Those who reproduced theatrical performance in these ways sought self-improvement and the distinctive theatrical sociability associated with Drury Lane.

- 28. To give but one example of publications promoting the theatre as a repository of wit, see: The jovial jester; or, Tim. Grin's delight...compiled by the choice spirits at the Shakespeare Bedford Coffee House Fox's Piazza Coffee-House The Rose Jupp's Covent-Garden Drury-Lane Theatre and other merry and diverting places of entertainment (London: W. Lane, [1786?]).

- 29. See A Compleat Collection of the Best and Most Admir’d Prologues and Epilogues, That have been spoken at the theatres and the spouting clubs (London: P. Wicks and R. Lloyd, 1771), p. 1.

- 30. For example, The sheep-sheering [sic]. A new song sung at Drury Lane Theatre. N.p., [1800 ?]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

Drury Lane Theatre generated a sizeable material diaspora. Consumers collected prints depicting their favourite players, creating their own virtual theatres at home with folios, displays of prints, or by extra-illustrating actors’ memoirs with images of their subjects. One could purchase china, tiles, fans, and other thespian-themed consumer objects to demonstrate a theatrical sensibility.31 Hundreds of playbooks, their title pages emblazoned with the cultural consecration of having graced its stage (‘as it is acted at the Theatre-Royal in Drury Lane’) and furnished with cast lists of its famous actors, dispersed and became the basis for British provincial theatre, private home theatricals, and productions in distant British colonies.

- 31. See Heather McPherson, ‘Theatrical Celebrity and the Commodification of the Actor’, in Julia Swindells and David Francis Taylor (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Georgian Theatre (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 192-212.

Public discourse invoking the name ‘Drury Lane’ grew to include mimicry and amateur theatrics, fetishistic collecting of texts and objects associated with the theatre, and theatrical criticism and performances, such that the theatre’s cultural impact was much greater than the sum of its audiences. The Theatre Royal in Drury Lane’s importance in shaping social identity during the eighteenth century was widely celebrated, perhaps nowhere better than in the playwright Arthur Murphy’s witty observation that in Britain’s body politic, there were four estates: ‘King, Lords, Commons, and Drury Lane playhouse.’32

- 32. Arthur Murphy, The Life of David Garrick, Esq., 6 vols (London: J. Wright, 1801), vol 2, p. 201.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Baer, Marc, Theatre and Disorder in Late Georgian London (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992).

Brown, Susan E., ‘Manufacturing spectacle: the Georgian playhouse and urban trade and manufacturing’, Theatre Notebook (vol. 64, n° 2, 2010), p. 58-81.

Burket, Mattie et al. (eds.), The London Stage Database. https://londonstagedatabase.usu.edu.

Cordner, Michael, and Peter Holland (eds.), Players, Playwrights, Playhouses: Investigating Performance, 1660-1800 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007).

Cowan, Brian, The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005)

Gorrie, Richard, Gentle Riots?: Theatre Riots in London, 1730-1780 (PhD thesis, University of Guelph, 2000).

Hume, Robert D., Henry Fielding and the London Theatre 1728-1737 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988).

Hume, Robert D., ‘The Origins of the Actor Benefit in London’, Theatre Research International (vol. 9, n° 2, 1984), p. 99-111.

Kinservik, Matthew J., Disciplining Satire: The Censorship of Satiric Comedy on the Eighteenth-Century London Stage (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2002)

Markman, Ellis, The Coffee House: a Cultural History (London: Phoenix, 2005).

McPherson, Heather, ‘Theatrical Riots and Cultural Politics in Eighteenth-Century London’, The Eighteenth Century (vol. 43, n° 3, 2002), p. 236–52.

Milhous, Judith, ‘Reading Theatre History from Account Books’, in Michael Cordner and Peter Holland (eds.) Players, Playwrights, Playhouses: Investigating Performance, 1660-1800 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), p. 101-131.

Milhous, Judith and Robert D., ‘Theatre Account Books in Eighteenth-Century London’, Script & Print: Bulletin of the Bibliographical Society of Australia and New Zealand (vol 33, n° 1-4, 2009), p. 125-35.

Moody, Jane, and Daniel O’Quinn (eds), The Cambridge Companion to British Theatre, 1730-1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Nicoll, Allardyce, The Garrick Stage: Theatres and Audience in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Sybil Rosenfeld (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1980).

Ritchie, Leslie, ‘The Spouters’ Revenge: Apprentice Actors and the Imitation of London’s Theatrical Celebrities’, The Eighteenth Century (vol. 53, n° 1, 2012), p. 41–71.

Straub, Kristina, Misty G. Anderson, and Daniel O’Quinn (eds.), The Routledge Anthology of Restoration and Eighteenth-Century Performance (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019).

Troubridge, St. Vincent, The Benefit System in the British Theatre (London: The Society for Theatre Research, 1967)

Van Lennep, William, Arthur Hawley Scouten, George Winchester Stone, Jr., et al., The London Stage, 1660-1800; a Calendar of Plays, Entertainments & Afterpieces, Together with Casts, Box-Receipts and Contemporary Comment, 5 parts (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1960-1968).

![‘Theatre Royal, Drury-Lane. This present Tuesday, September 18, 1798, Their Majesties Servants will act the tragedy called Macbeth', Yale University Library, 767 P69B, [1798].](/sites/default/files/styles/notice_full/public/2024-02/DRURY%205%20Capture%20d%E2%80%99%C3%A9cran%202022-09-11%20%C3%A0%2022.32.59_0.png?itok=F09fnlhw)

![S. Rawle, ‘New Theatre Royal Drury Lane, B. Wyatt Esqr., architect [graphic] / engraved by S. Rawle ; L. Francis delt’, Folger Shakespeare Library, 30373, late 18th to mid-19th century.](/sites/default/files/styles/notice_full/public/2024-02/DRURY%204%20DL%20garde%201_0.jpg?itok=wrbjTFAq)

![Smith, N., ‘The Old Theatre, Drury Lane, this front which stood in Bridges Street, was built by order of Mr. Garrick, previous to parting with his share of the Theatre [graphic]’, Folger Shakespeare Library, 27762, 1794.](/sites/default/files/styles/notice_full/public/2024-02/DRURY%203%20Old%20Theatre_0.jpg?itok=Ej16Cj4z)

![John Lodge, ‘Mr. Garrick delivering his Ode at Drury Lane Theatre on dedicating a building & erecting a statue to Shakespeare [graphic]’, Yale University Library, Lewis Walpole Library, 770.09.00.06, [1770?].](/sites/default/files/styles/notice_full/public/2024-02/DRURY%20DL%20garde%203.jpg?itok=STKUOORM)