Résumé

Gentlemanliness was a contested quality in eighteenth-century Britain. During the century, the term broadened away from men of lineage to encompass the rising middling sort. One criterion used to define these ‘new’ gentlemen’ was sociability, but this was a sociability that now had to conform to other qualities making the new gentlemen: industriousness, sincerity, honesty, benevolence. Lord Chesterfield's instructions to his son on the art of pleasing were now regarded as superficial, corrupting. This entry considers this shift in gentlemanly sociability which intersects with many other entries in DIGIT.EN.S.

Mots-clés

The concepts of gentlemanliness and sociability were intimately entwined in eighteenth-century British culture. Indeed, an appropriate sociability was integral to the definition of the gentleman, as the frequent occurrence of the word ‘gentleman’ in the DIGIT.EN.S encyclopedia testifies. However, exactly who was a gentleman and the forms of sociability that were indeed appropriate underwent a shift during the century.

Traditionally, a gentleman had been a patrician, a man of lineage, a member of the nobility or gentry who derived his wealth from the possession of land, of an estate. The word gentleman signified a high status that set a man apart from the lower orders, or plebeians. However, from the late seventeenth century British society was slowly being transformed. The growth of a commercial, consumer economy led to a decoupling of wealth from land ownership. Wealth (sometimes a very great deal of it) could instead be derived from ‘the translating of work […] into money’.1 This in turn created a new social grouping, the middling sort, which was neither patrician nor plebeian. The middling sort comprised some one million people in a population of seven million. Its ‘membership’ included traders and dealers from merchants to shopkeepers, professionals and some skilled artisans. They were literate, and many were aspirational, eager for public recognition to match their financial success. One way of achieving this was through claiming gentlemanly status through their personal achievements and merit.

- 1. Margaret R. Hunt, The Middling Sort: Commerce, Gender, and the Family in England, 1680-1780 (University of California Press, 1996), p. 209.

Definitions of ‘gentleman’ in Dr Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language, first published in 1755, captured this societal change. The leading definition was the traditional one: ‘A man of Ancestry’. Definition 2 was rather more capacious: ‘A man raised above the vulgar by his character or post’. By definition 5 Johnson had almost given up: ‘It is used of any man however high’. All that was needed to be a gentleman, it seemed, was to present to the outside world what Penelope Corfield calls ‘a sufficiently confident display’.2 That is, if you could claim to be a gentleman and get away with it, you were a gentleman. Elizabeth Marsh (1735-85), whose life has been chronicled by Linda Colley, is a good example of this. In 1769 she asserted ’I was the daughter of a gentleman’.3 Her father was a ship’s carpenter.

- 2. Penelope J. Corfield, ‘The Rivals: Landed and Other Gentlemen’, Negley Harte and Roland Quinault, eds, Land and Society in Britain, 1700-1914: Essays in Honour of F.M.L. Thompson (Manchester University Press, 1996), pp. 241-58.

- 3. Linda Colley, The Ordeal of Elizabeth Marsh: A Woman in World History (London: HarperPress, 2007), p. 23.

The social behaviour expected of the traditional, patrician gentleman was not very different from the stylish oratory and elegant self-presentation set out in Baldessare Castiglione’s influential Il Cortigiano as long ago as 1528 (translated into English in 1561 by Thomas Hoby as The Book of the Courtier). By the early eighteenth century, gentlemanly sociability was very closely associated with the concept of refined politeness. This still encompassed the art of pleasing in company and still had elite overtones in, for example, the writings of Lord Shaftesbury (1671-1713). However, the rise of cheaper print media, and in particular the periodical, meant that this art could now be disseminated to a wider audience that included the literate middling sort. Joseph Addison’s and Richard Steele’s Spectator and Tatler were two such vehicles. The young Dudley Ryder (1691-1756), a Hackney draper’s son, read these periodicals inter alia to fit himself for advancement through polite conversation. He rose to become a Member of Parliament and Chief Justice, for which services he was knighted.4

- 4. W. Matthews, ed., The Diary of Dudley Ryder 1715-16 (London: Methuen, 1939), p. 46.

Even before Johnson’s Dictionary crystallised the change in the meaning and scope of gentlemanliness there was evidence of the new middling-sort gentleman’s need for more specific guides to gentlemanly self-presentation, necessary to avoid the risk of challenge to his self-made status. In these guides we see a shift towards a polite style of sociability that was now adapted to the relationships between a trader or professional and his clients and business contacts. Samuel Richardson (1689-1761), middling-sort himself, advised readers of his Familiar Letters of 1741, written as a series of letters between family and friends, on appropriate sociability: ‘[…] what Company to chuse, and how to behave in it’. Sobriety, good sense and virtue were the characteristics to be sought in a friend. In conversation a man should be ‘frank and unreserved’ but should also know when to speak and when to allow another his turn.5 A more overtly didactic conduct guide of 1747, The Young Gentleman and Lady Instructed, advised readers to aim for goodwill, sincerity and honesty in conversation in society, and to avoid disputation, drunkenness, coarseness, and lewd language. The link to middling-sort lives and values as explored by Margaret Hunt was explicit: honesty in conversation was compared to that in trade and business, and the ‘knowledge of a man of business’ was more important than Latin and Greek, the Classical languages closely associated with an elite rather than a practical education.6

- 5. Samuel Richardson, Letters Written to and for Particular Friends on the Most Important Occasions … (London: Rivington and J. Osborn, 1741), Letter VII, pp. 13-15, and VIII, pp. 16-18.

- 6. The Young Gentleman and Lady Instructed in such Principles of Politeness, Prudence and Virtue, 2 vols (London: Edward Wicksteed, 1747), I, pp. 136, 232.

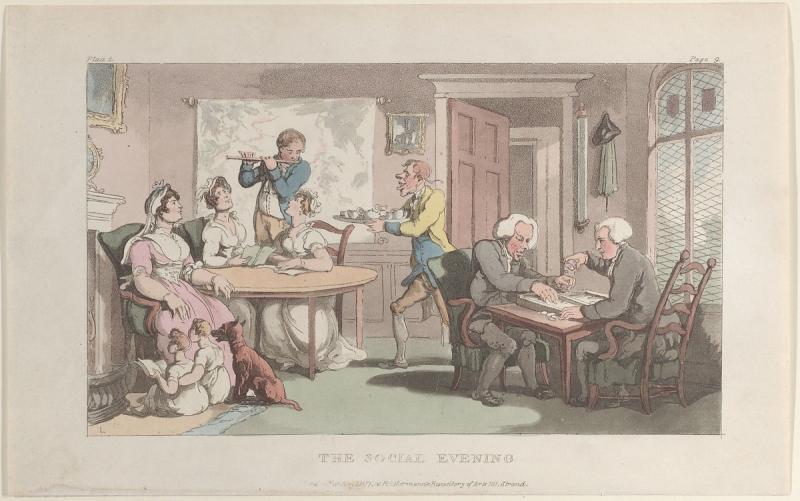

As middling-sort men’s confidence in the availability to them of gentlemanliness by personal merit grew, so too did this identity take on more oppositional overtones. They began to contrast favourably their version of virtuous, sober sociability with forms associated with the traditional gentlemen who were supposedly their superiors. In 1774, for example, there was a strong adverse response to the posthumous publication of Lord Chesterfield’s (1694-1773) Letters to his Son (composed between 1737 and 1768). Chesterfield’s patrician attitudes were now decried as outmoded and amoral. The reviewer for the Gentleman’s Magazine, the leading monthly periodical with a distinctly middling-sort national readership, regarded Chesterfield as using polite sociability as a mere hypocritical performance devoid of the honesty and sincerity of the middling-sort gentleman. Moreover, Chesterfield’s condemnation of debauchery extended only to that which was brutal and vulgar, leaving some members of the upper classes, ‘men of pleasure’, open to a charge of libertinism in their social lives. Had Chesterfield been ‘in a middling station of life’, continued the reviewer, then ‘virtue would have appeared more essential’.7 The rational, domestic sociability of the middling sort and their proper treatment of women could be contrasted with the drunken homosocial antics of the elite Hellfire Club or the hot-headed settlement of disputes by duelling.

- 7. Gentleman’s Magazine, July 1774, pp. 319-23.

Middling-sort gentlemanly qualities were also increasingly rehearsed and circulated in the Gentleman’s Magazine death notices, a feature for which it was noted and which by the final quarter of the century accounted for up to 10 per cent. of its pages. Although some were composed by the editors or lifted from other publications, most were submitted by relatives and associates of the deceased. They therefore reflect the social composition, values and ideals of the readership. In these notices, sociability was important in defining a man’s merit, provided it was allied to good sense and industrious habits. The July 1804 obituary of seventy-four-year-old Revd James Davies, a schoolmaster and curate in Clerkenwell, London, provides a flavour. Commended for his integrity and devotion to his work, Davies’ ‘social qualities’ also brought him friends, he was ‘fond of innocent hilarity’ and ‘society always took a cheerful tone from his presence’.8

- 8. Gentleman’s Magazine, July 1804, p. 696.

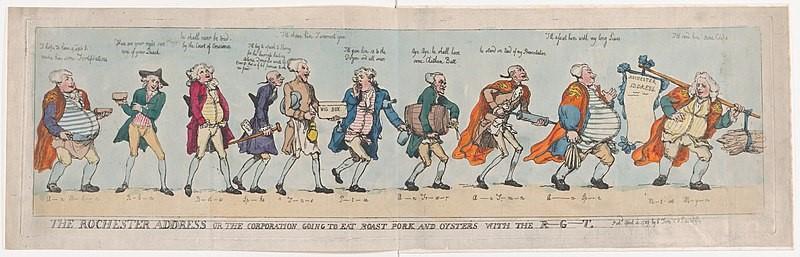

However, the claims of the middling sort to gentlemanliness always remained an ideal and were subject to mockery and challenge by the elite even at the outset. When a committee of shopkeepers and other middling-sort men tried to reform parish vestry government in Westminster in 1742, Lord Perceval (1711-70) sneeringly described them as having ‘Education just sufficient to enable them to read’ and as ‘spend[ing] all their leisure Time and sometimes more than they have conveniently to spare from behind the Counter, in some blind Coffee-House’ such that they ‘knew no longer how to confine themselves within their own proper Sphere’. In 1755, The Connoisseur lamented the rise of the middling-sort death notice: ‘When an obscure grocer or tallow-chandler dies at his lodgings at Islington, the news-papers are stuffed with the same parade of his virtues and good qualities, as when a duke goes out of the world’.9 Nor did patrician gentlemanly sociability entirely disappear. Nevertheless, the widespread adoption of a gentlemanly status through personal merit had some lasting impact. In the nineteenth century it was deployed both to reform the public social behaviour of the political classes and to stake a claim to inclusion in national politics by the middle class.

- 9. Lord John Perceval, Faction Detected by the Evidence of Facts (Dublin: for G. Faulkner, 1743), pp. 95-6, The Connoisseur, excerpted in the Gentleman’s Magazine, July 1755, p. 303.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Barry, Jonathan and Christopher Brooks (eds.), The Middling Sort of People: Culture, Society and Politics in England, 1550-1800 (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1994).

Corfield, Penelope J., Power and the Professions in Britain, 1700-1850 (London: Routledge, 1995).

French, Henry R., ‘The Search for the ‘Middle Sort of People’ in England, 1600-1800', Historical Journal (vol. 43, n° 1, 2000), p. 277-293.

Solinger, Jason D., Becoming the Gentleman: British Lliterature and the Invention of Modern Masculinity, 1660-1815 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

Williamson, Gillian, British Masculinity in the Gentleman’s Magazine, 1731-1815 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).