Résumé

The eighteenth century saw a proliferation of so-called Hell-fire Clubs, the members of which were invariably accused by society of promoting heavy drinking, sexual license, blasphemy, and Satanism, even if reality differed considerably from club to club. The most prominent of these societies belonged to the Duke of Wharton, the Earl of Rosse, and Francis Dashwood, providing a contrast to the contemporary focus on manners and social behavior.

Mots-clés

Few social phenomena have managed to capture the eighteenth-century imagination like the rise of secret societies called Hell-fire Clubs and the myths and panics surrounding them. In line with an enduring tradition of groups such as the Damned Crew, the Ballers, or the Mohocks, these gatherings of the well-to-do and aristocratic class were said to indulge in wild drinking, unrestrained sexuality, blasphemy, and even Satanism, providing a stark contrast to the contemporary focus on manners and social behavior. Contrary to their predecessors, however, who belonged to a more violent generation of rakes, Hell-fire Clubs operated with more sophistication and sought to remove themselves from the public eye rather than carouse in the streets – a withdrawal that only set the rumor mills of London to churn more heavily and has led contemporaries as well as historians to difficulties teasing apart legends from facts.

The first of these notorious societies congregated around Philip Wharton, the first Duke of Wharton (1698 – 1731), whose life was mired in controversy. Having married below his status, he was sent on a Grand Tour but escaped his tutor in Geneva and set out to France. There he met the exiled Pretender in 1716, marking the beginning of his ever-shifting allegiances. In his Moral Essays (1731-35), Alexander Pope, who lived near Wharton in Twickenham, describes him as a deeply ambivalent person: ‘A fool with more of wit than half mankind / Too rash for thought, for action too refin’d […] He dies, sad out-cast of each church and state / And, harder still! flagitious, yet not great’.1

- 1. Alexander Pope, Moral Essays: In Four Epistles (Glasgow: printed by R. Urie, 1754), p. 16, lines 204-205.

Wharton’s contrarian streak revealed itself once more upon founding the Hell-fire Club in the early 1720s, the primary objective of which was to have ‘theological discussion that bordered on the blasphemous in denying the Trinity and questioning the doctrine of the established Church’.2 Owing to the prevailing sentiment that the fault for society’s hardships lay in its members’ moral decay and lapsed faith, such theological arguments were seen as akin to Devil-worship. Wharton’s club thus became scandalous by default. Henry Fielding, in his Covent Garden Journal, later described the club members as a ‘set of infernal spirits’ and referred to literary accounts saying: ‘some of the members, it is said, [...] openly propagated Atheism, Deism, Immorality, Indecency, and all kinds of Scurrility against the best and worthiest Men of these Times’.3

The first known reference to the Hell-fire Club appears in Mist’s Weekly Journal on February 20th 1720, which ‘describes two clubs, the Bold Bucks and the Hell-Fires’ (Lord 52). Yet matters became truly public only after King George I issued a proclamation seeking to combat ‘impious Tenets and Doctrines’ which had been ‘advanced and maintained with much Boldness and Openness, contrary to the great and fundamental Truths of the Christian Religion’.4 The bill he sought to impose was defeated – unsurprisingly, Wharton himself had spoken passionately against it – but it nevertheless set London’s press aflame. On May 6th 1721, the Tory newspaper Applebee’s identified atheism as the prevailing problem of the time, stating that ‘it is no raising Sedition, or breaking the Peace, to take a Blaspheming Hell-Fire Club Man by the Throat’.5 On May 13th, the same publication insisted that members of such clubs ‘do not merit the Title of Men, but should be used like Brutes’.6 Broadsheets were distributed, decrying the demonic nature of these societies. In A Further and Particular Account of the Hell-Fire, Sulphur Society Clubs (1721), a list of possible members is published alongside the diabolical titles they allegedly gave themselves, such as ‘The King of Hell’ or ‘The Lady Polygamy’.7

Evidently, eighteenth-century London was quick to conflate anti-religious tendencies with sexual license. Multiple accounts speak of women participating in Wharton’s club, but according to Lord, such claims do not appear any more reliable than the highly polemical broadsheets of Grub Street (57). While there is little evidence pointing towards orgiastic happenings at Wharton’s Hell-fire Club, a letter from Lady Mary Montagu hints at a Hell-fire-adjacent society – the Schemers – of which Wharton was a ‘chief director’, and who met at the house of Viscount Hillsborough, himself a likely member of the Wharton Club. At Hillsborough’s estate, the Schemers concerned themselves with ‘the advancement of that branch of Happyness which the vulgar call Whoring’,8 and did so during Lent, the time of Christian self-denial. It appears likely that in the public perception, the Schemers’ sexual activities fused with the Hell-fire Club’s anti-Trinitarian stance. Either way, the furore around the club died down in 1722, once Wharton turned his attention towards freemasonry. His legacy remained prominent, however, and his life became the literary prototype for multiple ‘minor Satan’ figures in literature,9 such as the infidel Lorenzo in Edward Young’s Night Thoughts (1742-45) or the rakes in Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa Harlowe (1748).

Some scholars such as David Stephen Manning have come to question the existence of Wharton’s club in its entirety, arguing that it was ‘a satirical creation’ that ultimately turned into ‘a theological manifestation of what scholars would call a 'moral panic’.10 Others, such as Peter Clark, assert that ‘despite their various rituals, [they] were probably more concerned with drunkenness than irreligion’.11 Whether myth or reality, Wharton’s alleged club proved short-lived, and an Irish group around Richard Parsons, the Earl of Rosse (1702-1741), inherited the Hell-fire name and tradition in the 1730s and 40s. Parsons was ‘already infamous in polite society for his blasphemy and obscene wit, and his eccentric habit of receiving visitors in the nude’ (Lord 62). Parsons and his fellows met at the Eagle Tavern on Cork Hill, Dublin, before moving to a more secluded lodge at the top of Mont Pelier. That the rumors surrounding the Irish Hell-fire Club are more lurid is owed in part to the questionable reputation of its members, some of which were renowned for their heavy drinking, their quick tempers, and even murder in the case of Lord Santry (64). Stories of Satanism swiftly sprung up regarding Parsons’ club: they supposedly kept an empty chair for the Devil at their meetings, had ‘a familiar in the shape of a cat’ (66), and ‘assembled to drink hot scaltheen, a mixture of whiskey and butter laced with brimstone’ (Ashe 61).

Undoubtedly, however, the most famous Hell-fire Club belonged to Sir Francis Dashwood (1708-1781), who had already acquired a rakish reputation during his Grand Tour. However, most of the information regarding his more outlandish deeds – wooing the Czarina by pretending to be Charles XII and flogging penitents in the Sistine Chapel – stem from Horace Walpole (1717-1797),12 whose lifelong antipathy towards Dashwood makes him figure as a less reliable source. While Wraxall writes that Dashwood ‘far exceeded in licentiousness of conduct, any thing exhibited since Charles the Second’,13 his information is similarly secondhand and based on rumors. The exact date when Dashwood founded The Order of the Knights of St. Francis of Wycombe, sometimes also called The Friars of St. Francis or The Monks of Medmenham, is uncertain, but it must have happened during or shortly after Dashwood’s Divan Club, which held its last meeting on May 25th 1746.

The Brotherhood first met at the George and Vulture tavern and various townhouses, before relocating to West Wycombe and later Medmenham Abbey. The latter location became the source of much speculation, both in the press and in literature. John Wilkes’ description of the gardens, which he provided in a letter to his friend John Almon, was widely disseminated, and if not for the public fallout between him and another Medmenhamite, John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich, we might never have learned about the Brotherhood. What makes Wilkes’ depictions more reliable than Walpole’s is that none of the other friars refuted his claims, and that he was called ‘a false monk’ instead. Moreover, his letter was later reprinted in Edward Thompson’s The Poems and Miscellaneous Compositions of Paul Whitehead (1777).14 Whitehead was the steward of the Brotherhood and Thompson’s commemoration of his work was dedicated to Dashwood himself. It appears unlikely that such a work would engage in rumor mongering, especially since Dashwood was still alive at the time.

- 14. Edward Thompson, The Poems and Miscellaneous Compositions of Paul Whitehead (Dublin, 1777), p. xxiv.

Wilkes had little insight into the inner sanctuary, where ‘Eleusinian mysteries’ were practiced (xxvi), but he describes the gardens as decidedly sexualized. Near a cave entrance, ‘the statue [of Venus] turned from you,’ presenting ‘two nether hills of snow’ (xxvii). Over a couch one could read a command to youngsters to outdo themselves in romantic and sexual acts. Other Latin inscriptions such as ‘Peni Tento non Penitenti’ (‘a stiff penis, not penitence’) or ‘Hic Satyrum Naias victorem victa subegit’ (‘here the vanquished naiad subdued the conquering satyr’) likewise point to the erotic nature of the gardens (ibid). In 1751, Dashwood leased the abbey at Medmenham, some miles removed from West Wycombe and formerly belonging to a Cistercian Order. The abbey became famous for hosting the later meetings of the Brotherhood, and for the inscription above its doors which reads ‘Fay ce que voudras’ (‘do what thou wilt’), making it a sibling to Thélème, the anti-monastery of Rabelais’ Renaissance epos, thereby also adopting Rabelais’s humanist ideal to justify their debauchery. The cellar-books are fragmentary but reveal that from 1760 onwards, members regularly checked out bottles of wine ‘for their private devotion’ (Ashe 119f). The club’s activities seem to have occurred between June and October, when Parliament was in recess, and also involved ‘a tremendous A.G.M. that went on for a week or more’ (125).

Sources point towards an inner and an outer circle in the Brotherhood, the former allegedly mirroring the Apostles by counting twelve members (Lord 99). Influential politicians like George Bubb Dodington, John Tucker, and the Earl of Sandwich were certainly friars, as was the poet Paul Whitehead. Others of the first generation included John-Dashwood King, Dashwood’s half-brother, Thomas Potter, the Earl of Stanhope, and two Vansittart brothers. The second group centered around John Wilkes, likely introduced to the Brotherhood by Potter. He brought Charles Churchill and John Hall-Stevenson with him, and as the club later became public, the ensuing rift followed this generational fault line.15

- 15. Another friar was Simon Luttrell, a member of the Irish Hell-Fire Club. Evidence is less clear for Benjamin Franklin. If Franklin was involved, the date of his friendship with Dashwood would place him at the tail-end of the Brotherhood’s lifespan.

Women also played a part in Dashwood’s club, but not in the role of full-fledged members. The diary of a local tailor reveals that a delivery of habits for women was made to the abbey between 1751 and 1754, giving credence to rumors of irreligious dress-ups taking place at Medmenham (Ashe 130f). In 1760, John Armstrong wrote to Wilkes that he hopes ‘the Sisters are excused’ from shaving, especially anything below the chin.16 Likewise, in 1770, a letter from John Dashwood-King makes a reference to the Sisterhood (Ashe 129f). It is not entirely clear if these women were prostitutes or hailed from the upper class. Their anonymity seems to have been well-guarded, and while Fanny Murray, Sandwich’s mistress, is rumored to have been a member, neither Thompson nor anyone else provided any names.

- 16. Cited in Francis Dashwood, The Dashwoods of West Wycombe (London: Aurum Press, 1990), p. 37.

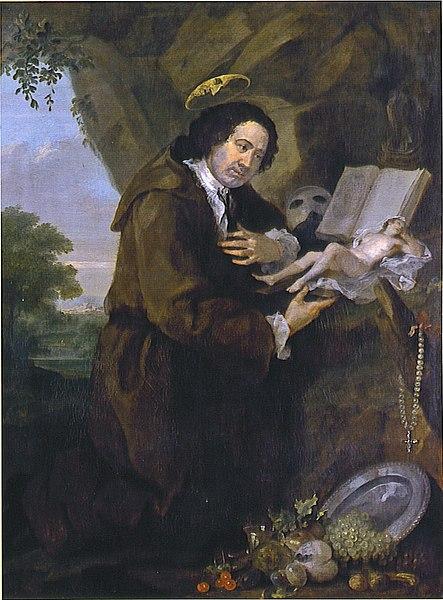

The presence of women, the Rabelaisian dictum, the elaborate gardens, and the convivial drinking point towards sexual gatherings at Medmenham during which the pursuit of pleasure was the norm, and which also involved transgressive behavior that clearly demarcates this form of sociability from the more manner-focused clubs dominating the social landscape at the time. The sparse references made by members of the Brotherhood corroborate the Hell-fire Club’s sexual nature, such as a letter from Sir William Stanhope, where he assures the Brotherhood that they have his prayers, ‘particularly in that part of the Litany when I pray the Lord to strengthen them that do stand’ (Dashwood 36). Additionally, they seem to have indulged in readings of satirical, occult, and pornographic literature, some of the books in the club’s library sporting ‘false bindings suggesting that they were prayer-books or collections of sermons’ (Ashe 124f). Dashwood’s anti-Catholic stance – four paintings exist of him that could be construed as blasphemous – and the delivered habits also point towards mock-religious ceremonies. Beyond that, however, little is known, and accusations of actual Satanism rather than blasphemy stretch the evidence too far. Details to the contrary stem predominantly from fictionalized accounts following Wilkes’ broadcasting of the Brotherhood’s existence, such as Charles Johnstone’s Chrysal (1760-65) or the anonymously published Nocturnal Revels (1779). Chrysal in particular speaks of ‘dissertations of such gross lewdness, and daring impiety, as despair may be supposed to dictate to the damn’d’,17 indicating that ‘the end of their meeting was to worship the Devil’ (249).

- 17. Charles Johnstone, Chrysal, or, The adventures of a Guinea, vol. 3 (London: T. Becket & P. A. De Hondt, 1766, 65), p. 239.

The political disagreement that ultimately led to the decline of the Brotherhood followed on the heels of Bute’s negotiation for peace in the Seven Years War. While Sandwich was a strident supporter, Wilkes proved pro-war and objected viciously. Consequently, Wilkes publicized the Brotherhood’s existence in the Public Advertiser on June 2nd 1763. His friends Churchill and Hall-Stevenson later added to the rumors: Hall-Stevenson in a highly obscene work, which sees Dashwood confess that, ‘like a Hotspur Young cock, he began with his mother / Cheer’d three of his sisters, one after another’;18 and Churchill in The Conference (1763) and The Candidate (1764), the latter of which famously begins its most revealing stanza with: ‘Whilst Womanhood, in habit of a Nun / At M—— lies, by backward Monks undone’.19

As an answer, Sandwich accused Wilkes of having composed the incendiary An Essay on Woman (~1755), a sexual and blasphemous parody of Pope’s An Essay on Man (1733-34) addressed to Fanny Murray. The Essay had been written by their fellow friar Thomas Potter, with minor additions by Wilkes, and had likely been shared with much enthusiasm in the Brotherhood. Despite the hypocritical nature of Sandwich’s accusations, the public exposure of the Essay proved effective, leading to Wilkes’s banishment. Sandwich’s behavior towards Wilkes had made him so unpopular with the general populace, however, that he earned himself the nickname ‘Jeremy Twitcher’, linking him to a character from John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728).20

- 20. Town and Country Magazine, November 1769, pp. 561-562.

The meetings of the Brotherhood continued less frequently after 1763, and evidence becomes conflicting. On March 22nd 1766, Tucker wrote that he ‘found the Chapter Room stripped naked’ (cited in Ashe 166), yet on August 19th 1770, Dashwood informed Sandwich that, together with ‘Father Paul’, they ‘will march to Medmenham the next day’ (Dashwood 46). In 1776, a revival was attempted. The Morning Post revealed that Sandwich ‘is determined to restore it to its original glory’,21 but the publication also called Sandwich the last remaining survivor, even though Dashwood died years later in 1781. In any case, the abbey was leased only until 1778, so that year marks the definitive end of Dashwood’s Hell-fire Club. Its story, however, lives on, having subtly inspired Jane Austen’s Dashwood family in Sense and Sensibility (1811) and multiple contemporary pop cultural depictions as well.22 Indeed, over time, the Hell-fire Clubs – from Wharton over Parsons to Dashwood – have blended into a singular eighteenth-century legend that, to this day, galvanizes the imagination. Ultimately, while these gatherings provided a setting for sociable interactions between their respective members, the secrecy surrounding them, the myths born of that secrecy, and finally the debauchery and anti-religious sentiment that ensued, mark the Hell-fire Clubs as rakish oddities in the manner-focused clubs and societies of eighteenth-century Britain.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Ashe, Geoffrey, The Hell-Fire Clubs: A History of Anti-Morality (Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Limited, 2000).

Barchas, Janine, ‘Hell-Fire Jane: Austen and the Dashwoods of West Wycombe,’ Eighteenth-Century Life (vol. 33, n° 3, 2009), p. 1-36.

Blackett-Ord, Mark, The Hell-Fire Duke (Windsor Forest, Berks.: The Kensal Press, 1982).

Lord, Evelyn, The Hell-Fire Clubs. Sex, Satanism and Secret Societies (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2010).

Mannix, Daniel P., The Hell-Fire Club (New York: Ballantine Books, 1959).