Résumé

John Thelwall was an orator, journalist, poet, and elocutionist, who remains best-known for being the subject of a Treason Trial in 1794, and for his involvement in radical groups such as the London Corresponding Society in which he helped to forge a new model of political sociability. His interest in finding the best means to cement the public together into a coherent social form was a life-long project, traversing many domains, including alehouses, taverns, debating societies, lecture halls, theatres and a wide variety of print productions.

Mots-clés

John Thelwall was born in Chandos Street in Covent Garden on 27 July 1764, the son of a silk mercer. After the death of his father, Joseph, in 1772, his mother Mary attempted to continue the family business and Thelwall tried his hand for a time as a silk merchant, but soon looked elsewhere to help relieve his family’s increasingly desperate economic situation. He attempted a number of careers: painting, acting, tailoring, and in 1782 he was articled as clerk to an attorney and later began to study for the bar. But it was a literary life that most appealed, and in 1786 he resolved to make a living as a writer.1 He had published a number of articles while still pursuing a legal career, then in 1787 he published Poems on Various Subjects, and became the editor and main contributor to the Biographical and Imperial Magazine.

- 1. John Thelwall, ‘Memoir’, Poems written in retirement (Hereford: Printed by W.H. Parker, 1801), p. xviii.

Initially in his private studies Thelwall was drawn to religious subjects, and was a ‘complete church-and-king man’.2 In the 1780s, he became strongly motivated by the attractions of literary culture, finding in the cut-and-thrust of debating societies and literary periodicals, which welcomed views of all political bents, a new form of identity. As his second wife, Cecile Thelwall wrote in her 1837 biography: ‘the prospect of mingling in circles of society, more correspondent to his taste and turn of mind than those to which had hitherto been confined, had altogether formed an association intoxicating’ (Thelwall 18). It was this love of ‘circles of society’ in which his own views might be reflected and furthered that defined much of his career in the 1780s and 1790s. He regularly attended debates and eventually ran the Society for Free Debate at Coachmaker’s Hall. He credited the attempts to close down debating societies as his primary motivation for switching political allegiances and embracing the reform movement, suggesting the importance of physical gathering to his thinking.

- 2. Cecile Thelwall, 'The Life of John Thelwall, by His Widow', 2 vols (London: John Macrone, 1837), 1, p. 22.

The Coachmaker’s Hall debating Society was closed down in 1792, not long after a Royal Proclamation against seditious writings. At this time, Thelwall was living in Maze Pond Road, near St Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals, and he became involved in a weekly medical debating club called the Physical Society. This was part of what became a lifelong interest in materialism, which underpinned many of his ideas through to the 1830s.3 In 1793 he published an Essay Towards A Definition of Animal Vitality based on ideas tried out at the Physical Society, in which he argued that life was not spiritual but consisted of organized matter acted upon by stimuli that he compared to electricity. This materialist account of life underpinned much of his radical politics and his literary output, not least in his understanding of sympathy as materially based. For Thelwall, the material world offered an explanation for the attachments of human society, so that communities were founded upon a natural attraction, ‘like the correspondent particles of matter, [that] have a tendency to adhere whenever they are brought within the sphere of mutual attraction’.4 This commitment to the social and political potential of materialism saw him ejected from the Physical Society, but in the same year that he published An Essay Towards A Definition of Animal Vitality he published his genre-bending The Peripatetic, a compendium of verse and prose that united sentimental fiction, with gothic elements, underpinned by his idiosyncratic materialism.

- 3. Thelwall’s interest in materialism has been most thoroughly explored by Yasmin Solomonescu in John Thelwall and the Materialist Imagination (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

- 4. John Thelwall, 'The Peripatetic, or Sketches of the Heart, of Nature and Society', in A Series of Politico-Sentimental Journals in Verse and Prose of the Eccentric Excursions of Sylvanus Theophrastus (London: Printed for the Author, 1793), vol. 1, p. 83.

Thelwall’s political career began when he was a poll clerk for the Westminster election of 1790, in which role he impressed John Horne Tooke, who he subsequently referred to as his ‘intellectual and political father’ (Thelwall 76). As the reform movement gathered momentum in 1793 he attended meetings of a variety of political groups including a number of more gentlemanly organizations such as the Friends of the Liberty of the Press (which was formed to celebrate the achievements of Thomas Erskine in defending the publication of Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man), the Borough Society of the Friends of the People, and the Society for Constitutional Information. In October 1793 he began attending meetings of the London Corresponding Society, a more socially diverse group to which he was introduced by Joseph Gerrald. He understood his contributions to these groups as bringing together into unity what might otherwise be a disaggregated set of individuals and to animate the collective with a vital spark. The ‘people’ however must first be organized, as he wrote in Natural and Constitutional Right:

If the people are not permitted to associate and knit themselves together for the vindication of their rights, how shall they frustrate attempts which will inevitably be made against their liberties? The scattered million, however unanimous in feeling, is but chaff in the whirlwind. It must be pressed together to have any weight.5

- 5. John Thelwall, Natural and Constitutional Rights of Britons to Annual Parliaments, Universal Suffrage, and Freedom of Popular Association; being a vindication of the motives and political conduct of J. Thelwall, and of the London Corresponding Society, in general (London: Printed for the author, 1795), p. 68.

Thelwall took upon himself the task of pressing together the scattered million into a coherent, unified body, which he did through a variety of means including printed publications, staged interventions at theatrical performances, and a series of public lectures.

An early lecture on William Godwin’s Political Justice was initially offered to raise funds to send LCS members to the Edinburgh Convention, but it was sufficiently successful that he repeated the lecture and wrote more, which he delivered at various venues, occasionally taking out newspaper advertisements to increase his audience.6

- 6. See for example Morning Post, 12 February 1794.

During early 1794 he was extremely active in the LCS and after he moved into Beaufort Buildings in the Strand in April, his home became the unofficial headquarters of the organization, housing meetings of the central organizing committee as well as offering lectures. On 13 May 1794 Thelwall was arrested by the British government, who rounded up the leaders of the reform movement on the suspicion that they were plotting to usurp the authority of the constitutional monarchy by attempting to represent the people directly by organizing a British convention, on the model of that of France. Thelwall was imprisoned in the Tower of London until he was indicted on a charge of Treason, when he was moved to Newgate. During the period he wrote a series of poems published the following year as Poems Written in Close Confinement in the Tower and Newgate, Under Charge of High Treason. These poems include a series of Anacreontic and convivial poems, which celebrate the glass being passed around, a celebration of conviviality which takes on a particular poignance when written in the context of imprisonment on a charge of Treason, facing a potential death penalty.

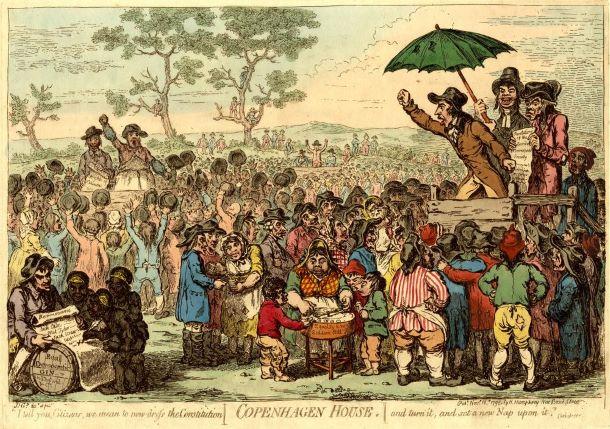

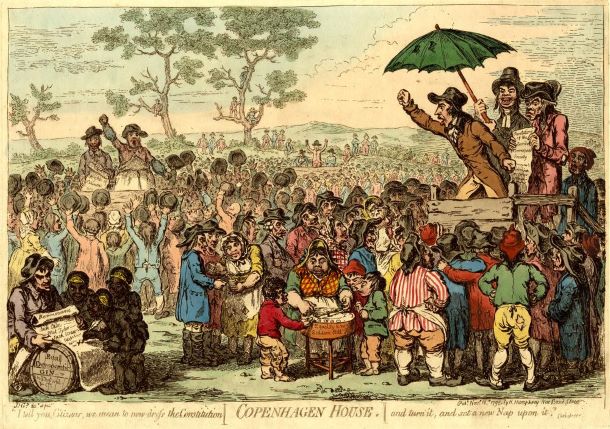

At the high-profile Treason Trials, Thewall, Thomas Hardy and John Horne Tooke were acquitted, a vindication that marked a major victory for the reform movement. But the victory was short-lived. The government quickly responded with a series of repressive measures circumscribing political gathering, typified by the ‘Gagging Acts’ of December 1795, which restricted public meetings to fifty persons and required that a license was granted for lectures and debates. Thewall understood these acts as being personally aimed at himself, which for all its hubris, was plausible. Certainly, the government were concerned about the agitation his lectures were causing. In October 1795, in the run up to the passing of the Gagging Acts, ThelwalI had lectured at Copenhagen House at a mass open air meeting attended by up to 200,000 people, protesting against the government on a variety of issues.

Shortly afterwards, on October 29 the King’s Carriage was attacked which provided a pretext for the passing of the Gagging Acts, which effectively outlawed Thelwall’s lectures.

In the run up to the passing of the gagging acts William Godwin published his Considerations on Lord Grenville’s and Mr Pitt’s bills (1795), which attacked the Two Acts as unnecessarily repressive, but which along the way attacked Thelwall’s lectures, characterizing them as occasions of intemperate excess appealing only to the passions and lacking the necessary moderation of sober philosophical enquiry. Despite this, and at considerable personal risk, Thelwall continued to lecture, but now under the guise of lectures on classical history.

Earlier in his career Thelwall had used theatrical performance as a means of political protest, attending a performance of Ottway’s play Vencie Preserv’d at Covent Garden on 1 February 1793, where he led a group of friends in cheering loudly and pointedly at a speech which expressed republican sentiments. In both the theatre protest and his history lectures Thelwall used history as a cover, to encourage sentiments which Pitt’s government had tried to outlaw. By doing so, he attempted to organize the scattered million into a coherent social whole, combining in solidarity against the repressive measures of a tyrannical power.

Eventually, however, Thelwall withdrew from London, embarking on a lecture tour in East Anglia, then joining Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth in Nether Stowey on 17 July 1797.7 He enjoyed a number of pleasant days in this company, and resolved to join the poets, suggesting a change in preference from the hurly burly of the political crowd in London to a more intimate company, along the lines Godwin had suggested. Coleridge, however, was evasive and Thelwall eventually settled at Llyswen on the Banks of the Wye. Here he attempted to live as a farmer, writing poetry in his spare time, and in 1801 published his Poems Written Chiefly in Retirement.

- 7. Thelwall’s relationship with Wordsworth and Coleridge and his influence on their work has been explored most fully by Judith Thompson in John Thelwall in the Wordsworth Circle: The Silenced Partner (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

Around this time he began to teach elocution or what he called ‘the science of human speech’, using his own experiences of living with a speech impairment to help pupils. His earlier political principles continued to underpin his thinking, and he understood his elocution lessons in political terms as ‘enfranchisement of fettered organs’.8 This venture was a success enabling him to return to London, initially living in Bedford Place before moving to Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1809. Here his Institute of Elocution thrived until 1818 when a resurgence in the reform movement prompted Thelwall to re-enter the world of politics more actively. He purchased the journal The Champion, which he began to edit, publishing a series of articles at the time of the Peterloo Massacre that were powerfully condemnatory. In 1819 he reopened his elocutionary school in Brixton and for the next fifteen years he combined his elocutionary project with lecture tours and courses on politics and history. He also continued his journalistic career with The Monthly Magazine (1825) and The Panoramic Miscellany (1826). He was still lecturing until the time of his death on 17 February 1834.

- 8. Thelwall, A Letter to Henry Klein Esq. on imperfect developments of the faculties, mental and moral, as well as constitutional and organic, and on the treatment of Impediments of Speech (London, 1810), p. 9. For a discussion of this letter see Emily B. Stanback, “Disability and Dissent: Thewall Elocutionary Project”, John Thelwall: Critical Reassessments, ed. Yasmin Solomonescu, special issue, Romantic Circles: Praxis Series 12 (September 2011); http://www.rc.umd.edu/praxis/thelwall/HTML/praxis.2011.stanback.html.

The discovery by Judith Thompson in 2004 of a one-thousand-page manuscript in Thelwall’s hand has confirmed that Thelwall continued to be interested in politics, print and ‘the social virtues’ until his death. As Jon Mee has argued, throughout his career Thelwall did not ‘simply act in the name of ‘the people’, but wrestled with difficult issues of how to create and address a ‘public’ for a democratic culture’.9 At the core of this lifelong attempt to create a coherent democratic ‘public’ was a complex relay between the possibilities of a print public sphere, and forms of in-person sociable interaction and speech.

- 9. Jon Mee, Print Publicity and Popular Radicalism in the 1790s. The Laurel of Liberty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 187.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Barrell, John, Imagining The King’s Death: Figurative Treason, Fantasies of Regicide, 1793-1796 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Green, Georgina, The Majesty of the People: Popular Sovereignty and the role of the writer in the 1790s (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Roe, Nicholas, Wordsworth and Coleridge: The Radical Years (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988).

Scrivener, Michael, Seditious Allegories: John Thelwall and Jacobin Writing (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2001).

Solomonescu, Yasmin, John Thelwall and the Materialist Imagination (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

Thelwall, John, Selected Poetry and Poetics, ed. Judith Thomspon (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

Thelwall, John, The Politics of English Jacobinism, Writings of John Thelwall, ed. Gregory Claeys (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 1995).

Zimmerman, Sarah, The Romantic Literary Lecture in Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).