Résumé

As British portrait painters’ working spaces evolved from craftsmen’s workshops into painting rooms supplemented with exhibition rooms and fitted out to accommodate Society patrons, they became places of intense sociability. Savvily located in the cultural and commercial capitals of the day (in particular Bath and London), they provided the material stages on which rising artists sought to deploy newly acquired social skills in their quest for custom and a fine reputation.

Mots-clés

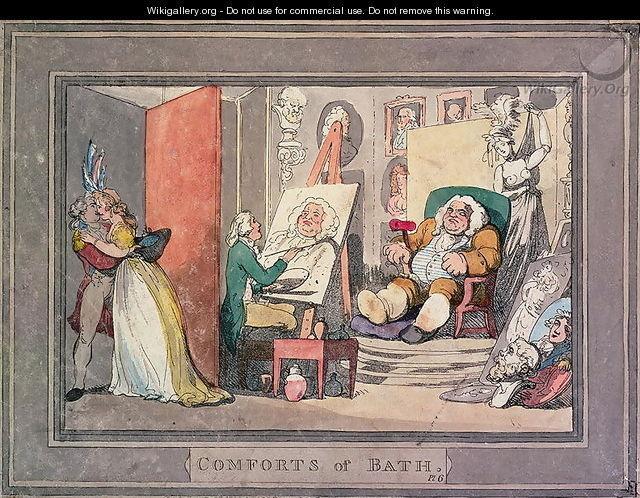

Among the many artistic venues which flourished in Britain over the course of the eighteenth century, the artist’s studio provided the locus for a rich middle- and upper-class sociability involving a range of actors: painters, assistants, apprentices, sitters, patrons, servants, admirers, friends, lovers and even pets. Due to its location either inside of or attached to the artist’s private home, the ‘painting room’, as the place where sittings took place was called, formed a hybrid space where private, even intimate relationships intersected with economic transactions and the development of a taste for the arts among a large public. It was often supplemented with a ‘showroom’ serving as both an ante-chamber to the artist’s creative sanctuary and an art gallery. With a growing number of men and women with money and a desire for publicity commissioning their portraits, the business of Society portraitists thrived, with London serving as a magnet for those eager to bring their careers to a grand finale: Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), moving from Bath in 1774 to end his career in Pall Mall, or George Romney (1734-1802), settling in the capital in 1775 after an early career in Cumbria and a few years on the Continent, are just two of many examples. As competition intensified among portrait painters on an expanding market for the arts, so the need for mastering the art of pleasing patrons, male and female, old and young, bourgeois and high-born, increased. The story of eighteenth-century studio sociability is largely informed by the new polite and commercial circumstances which made their way into the artist’s working space to transform it into one of constant negotiation between art, rank, gender and money.

Art historian Lucy Peter has shown how, from places more akin to craftsmen’s workshops in the seventeenth century (many of them in the hands of foreigners), the studios1 of eighteenth-century British portraitists gradually turned into ‘grand and lofty affair[s]’,2 with artists such as Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) or Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) eventually running large, well-staffed and elegant places able to accommodate high-born visitors. Already, c. 1716, the depiction of an artist’s studio by Flemish-born and occasional portrait painter Peter Tillemans [Fig. 1] presented a tidy and well-organised stage for informed artistic conversations between artist and friend –here a suitably bewigged Tillemans and Reverend Cox Macro– or artist and pupils.

- 1. The word ‘studio’ will hereafter be used to specifically designate the ‘painting room’, as distinct from the ‘showroom’ which often adjoined it.

- 2. Lucy Peter, ‘The Artist at Work’, in Anna Reynolds, Lucy Peter and Martin Clayton (eds.), Portrait of the Artist (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2016), p. 92-157.

Reality often differed from such programmatic representations. In that respect, the notebooks of art commentator George Vertue (1684-1756) offer illuminating insights into the uneven outlook of London artists’ daily lives in the first decades of the eighteenth century, when many drank, entertained prostitutes and sometimes even brawled in their home-based studios. Vertue, for instance, reported in 1726 that, having lost his nose in the ‘Garden of Venus’, the painter Christian Richter (1678-1732) found himself prevented from ‘reaping such advantages by his Art Sutable to his meritt his face being no Agreable prospect for fine Ladys to see those scars were rather a motive of compassion than to inspire their graces & charmes.’3 For obvious reasons, the allure which the ‘alternative’ studio, complete with an eccentric, possibly disreputable owner, would acquire in the Romantic era never proved a strong selling point for the Georgian portrait painter.

- 3. George Vertue, ‘Vertue Notebooks: Vertue III’, The Volumes of the Walpole Society (vol. 22, 1933–4), p. 25.

Portraitists’ studios were, indeed, places where polite manners were all-important and the art of conversation had to deploy itself as productively as possible during the sittings. In accordance with this, Vertue lavished endless praise on painters able to strike the right note with clients, by behaving in a ‘genteel’, ‘agreable’, ‘affable’, ‘regular & sober’ manner and with ‘plain open sincerity’ (Vertue 22). In his 1711 The Theory of Painting, portrait painter Jonathan Richardson (1667-1745) had insisted that his colleagues develop the social skills and artistic culture which would allow them to entertain their sitters with gentlemanly subjects, and thereby endow their features with the joyful or peaceful air expected in portraits. Eliciting the expressions commonly associated with, among other pleasant topics, ‘the sight of a friend, a reflection upon a scheme well laid, a battle gained, success in love, a consciousness of one’s own worth, beauty, wit, agreeable news, truth discovered’ was clearly the portraitist’s job.4

- 4. Jonathan Richardson, The Works of Jonathan Richardson, Consisting of 1. The Theory of Painting 2. An Essay on the Art of Criticism 3. The Science of a Connoisseur (London: T. Davies, 1773), p. 100.

To this end, the painter needed to create a propitious studio atmosphere: ‘the painting-room’, Richardson stipulated, ‘must be like Eden before the fall, like Arcadia; no joyless, turbulent passions must enter there’ (100). In his study of Joshua Reynolds as a ‘painter in society’, Richard Wendorf has pointed out how the octagonal painting room of the first president of the Royal Academy was praised by visitors precisely for its adherence to the recommendations of his predecessor.5 Reynolds’s gift at dealing with children was much praised by his contemporaries. In a drawing depicting the elderly Academician in his famous red armchair as he observed a little girl play with a pet dog (British Museum number 2007,7008.1),6 John James Chalon vividly evoked the late master’s ability to get the best out of his most diffident studio sitters.

In a world of culture torn between rapid commercialisation and a tradition of disinterested civic humanism, the insistence on refined deportment on the part of artists was, in large part, designed to play down the fact that the studios of successful portraitists were an integral part of the new market for the arts. On coming back from a thirty-year long stay in the British capital, the Swiss-born commentator Jean André Rouquet reported that many portrait painters in England also had, often adjacent to their painting room, a showroom or art gallery which he described in 1756 in his The Present State of the Arts in England:

Every portrait painter in England has a room to show his pictures, separate from that in which he works. People who have nothing to do, make it one of their morning amusements to go and see these collections. They are introduced by a footman without disturbing the master, who does not stir out of his closet unless he is particularly wanted. If he appears, he generally pretends to be about one person’s picture, either as an excuse for returning sooner to his work, or to seem to have a great deal of business, which is oftentimes a good way of getting it. The footman knows by heart all the names, real or imaginary, of the persons, whose portraits, finished or unfinished, decorate the picture room: after they have stared a good deal, they applaud loudly, or condemn softly, and giving some money to the footman, they go about their business.7

- 7. Jean André Rouquet, The Present State of the Arts in England (Dublin: Printed for G. and A. Ewing, 1756), p. 39-40. The original work was published in French in 1755.

During her brief stay in London some forty years later (1803-1805), French painter Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun took note of this enduring custom, adding that the gratuity paid to servants for such visits was often ultimately pocketed by the painter, for whom it represented a much welcome financial complement.8

- 8. Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Souvenirs. Le Temps retrouvé (Barcelone : Mercure de France, 2020), p. 530.

Private showrooms were undoubtedly precious in promoting an artist’s talent in cities without a public exhibition – such as Bath in the second half of the eighteenth century –, or during such an exhibition if one wanted to capitalise on the event – as became the fashion in London following Gainsborough’s conflict with the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition’s hanging committee in 1784. Advertising strategies were often carefully planned by artists who, for instance, variously opted for roof lighting, candle light, displaying half-finished works, exhibiting large numbers of portraits, or just a chosen few. On one occasion even, in 1781, recorded by Horace Walpole in his Anecdotes of Painting in England, a concert was organised in Thomas Beach’s showroom in Bath,9 with portraits of local figures tastefully hung to serve as a bait for prospective clients and feed their aspirations to momentary celebrity in paint.

- 9. Horace Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England: 1760-1795, ed. F.W. Hilles and P.B. Daghlian (New Haven and London, 1937), p. 20-22, quoted in Susan Sloman, Gainsborough in Bath (New Haven and London: Yale University Press), p. 20.

It is thus no surprise that artists should have set up their homes and studios in the genteel areas where their patrons lived. In London, many, including William Hogarth and Joshua Reynolds, made the move up and westward from the area around Covent Garden to Leicester Fields, while Thomas Gainsborough joined Nathaniel Hone and Richard Cosway (1742-1821) on Pall Mall. Just like that of the Assembly Rooms in Bath, the proximity of the luxury trade (James Christie opened his great auction room on Pall Mall in 1768) also ensured a regular influx of wealthy shoppers ready to factor a visit to the portrait painters’ rooms into their morning rounds.

No matter how business-savvy, portraitists displayed mixed feelings towards that often busy extension of their working space: a gruff Thomas Gainsborough had, for instance, to be coaxed into meeting his visitors there (see his 1767 letter to William Jackson for a taste of how reluctant he was to be interrupted) and John Hoppner (1758-1810) even had a special front door for sitters. Towards the end of his life, William Hogarth had become increasingly irritable and removed his painting room to his backyard in Chiswick, above the stables, where it was to be reached via a dark and narrow staircase. Others, like Nathaniel Hone (1718-1784), willingly took their guests round the gallery of their own works and George Romney, eager to build a custom on his return from Italy in 1775, is said to have made himself available almost night and day. Painting rooms were often built in an outbuilding lying at the back of the artist’s house: for some, this was a way to make them quieter and more exclusive places; for others, it ensured that they would only be reached after a mandatory visit to their collection. The two strategies were not mutually exclusive, though, and, at 87 Pall Mall, Gainsborough had his landscapes lining the walls of the narrow corridor leading to his painting room, on top of the parlour showrooms on the ground floor.10

- 10. This was later recalled by portrait painter William Beechey’s son. See Susan Sloman, Gainsborough in London (London: Modern Art Press, 2021), p. 55.

Though rumours had it that bachelors like Romney or Reynolds privately entertained lady friends in their painting rooms outside regular working hours, it was, by all accounts, rare to be sitting alone for one’s likeness. Of the late portrait painter John Hamilton Mortimer (1740-1779), the memoirist Henry Angelo for instance wrote that, c. 1764, ‘[h]is studio was indeed the morning lounge of many distinguished gentlemen, and almost all of the professional men of talent of his day’.11 Similarly, the painting room of Joshua Reynolds was reported by his pupil and biographer James Northcote to have often been filled with a posse of friends, pupils and admirers. This is how the Society portraitist’s studio soon morphed into a stage, with the artist as director choosing costumes and poses for his actors, and the portraits themselves forever freezing the social performance that had surrounded their creation. The frequent presence of a mirror in the room (Reynolds had one placed obliquely to the canvas) no doubt added to the theatrical quality of the experience of sitting both to an artist and to a voyeuristic public, albeit a limited one. The titillation was presumably heightened in the case of beautiful female sitters. One further inconvenience was that, with so many onlookers, portraitists frequently had to put up with running commentary on and interruption of work in progress, a state of affairs which Jonathan Richardson seems, for his own part, to have found difficult to handle and against which he had warned young artists (Richardson 13).

- 11. Henry Angelo, Reminiscences of Henry Angelo, with Memoirs of his Late Father and Friends (London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1830), p. 139.

Yet, depending on the popularity of the portraitist, negotiations were not always conducted in favour of the patron, especially when the artist had asked for a down payment of half the price on receiving the commission, as was common. This is how a famously ill-humoured Romney is reputed to have bullied aristocratic female sitters into wearing what he had chosen for them, thus placing them ‘to a significant degree within his power’ (Wendorf 123). In Hanging the Head. Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteenth-Century England, Marcia Pointon has shown how much more intricate and psychically violent these dynamics were for women, particularly young ones.12 As the desire to have one’s likeness taken by a fashionable painter vied with that to keep control over one’s image, even women of high birth ended up giving in to the male portrait painter. Similarly, discussions over prices and completion dates would, on occasion, mar the smooth deployment of studio sociability, a sign that power relations between individuals of different ranks, genders, wealth and celebrity made themselves felt even in the very heart of artistic creativity.

- 12. Marcia Pointon, Hanging the Head. Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteenth-Century England (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993), p. 177-193.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Belsey, Hugh, ‘Some Artists’ Studios in 1785’, Windows on that World. Essays on British Art Presented to Brian Allen (Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2012), p. 120-121.

Kidson, Alex, ‘George Romney: An Introduction’, in George Romney. 1734-1802, exhibition catalogue (London: The National Portrait Gallery, 2011).

Mannings, David, ‘At the portrait painter’s. How the painters of the eighteenth-century conducted their studios and sittings’, History Today (vol. 27, 1977), p. 279-287.

Mesplède, Sophie, ‘Pets in the Studio. Mediating Artistic Sociability in a Polite and Commercial Age’, in Valérie Capdeville and Pierre Labrune (eds.), Sociable Spaces in Eighteenth-Century Britain: A Material and Visual Experience, Études anglaises (vol. 74, n° 3, 2021), p. 336-352.

Waterfield, Giles (ed.), The Artist’s Studio (Compton Verney: Hogarth Arts, 2009).

Wedd, Kit, Lucy Peltz and Cathy Ross, ‘1685-1800. Markets for Art: Covent Garden and Leicester Square’, in Kit Wedd, Lucy Peltz and Cathy Ross (eds.), Artists’ London (London: Merrell Publishers, 2003), p. 32-47.