Résumé

Richard Steele was one of the most important and controversial figures of early eighteenth-century sociability and politeness. Perhaps best known for his contributions to periodical literature, Steele achieved fame for the style and content of his writing, which had a long legacy during the eighteenth century. The successful formula was to offer cultural comment (including theatre criticism, poetry and ‘gallantry’, mixed with moral guidance) in a periodical essay format, with some politics and news, lightened with humour. He was nevertheless also a highly partisan polemicist and had a relatively circumscribed view of who constituted the ‘people’.

Mots-clés

This article will not repeat data easily accessible elsewhere about Steele’s career as a politician and writer but instead focus on his ideas relating to sociability.1 Even so, there are elements of his life that are worth highlighting for the influence they may have exerted on his own sociability and his attitudes towards it. One important step was his decision to enlist in the army, first in 1692 in the Life Guards, which had a strong identity as a band of ‘gentlemen’, and then in 1695 in the Coldstream regiment, in which he captained a troop. Steele later observed that ‘There is no sort of People whose Conversation is so pleasant as that of military Men’.2 The military had its own codes of sociability, including duelling when an affront was offered – a practice in which he once engaged and of which he then became a vocal critic.3

Another feature of his life was his long-standing friendship with Joseph Addison, with whom he collaborated on the celebrated periodicals The Tatler (1709-10, with Steele as the major partner), The Spectator (1711-12) and The Guardian (1713). He and Addison were associated with Child’s Coffee House and were also members of the Whig Kit-Kat Club, which was both political club and socio-cultural space. Membership gave Steele access to writers, such as William Congreve and fellow soldier-writer Sir John Vanburgh, as well as to an extensive patronage network of Whig leaders. The club’s reputation for genteel sociability was enhanced by a series of portraits painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller, including the one of Steele here.

In one of his first publications, The Christian Hero (1701), he articulated his conviction that God had created man as a sociable animal: ‘We are fram'd for mutual Kindness, good Will and Service, and therefore our Blessed Saviour has been pleased to give us […] the Command of Loving one another’.4 This informed his belief in charity and toleration of dissent. Steele was clearly a man capable of developing strong ties both to groups and to individuals, and was naturally drawn to sociable spaces, including the theatre, for which he wrote plays. In 1714 he became the manager of Drury Lane. He was also interested in community: of nation; of Protestants (including dissenters); of party; and of polite society.

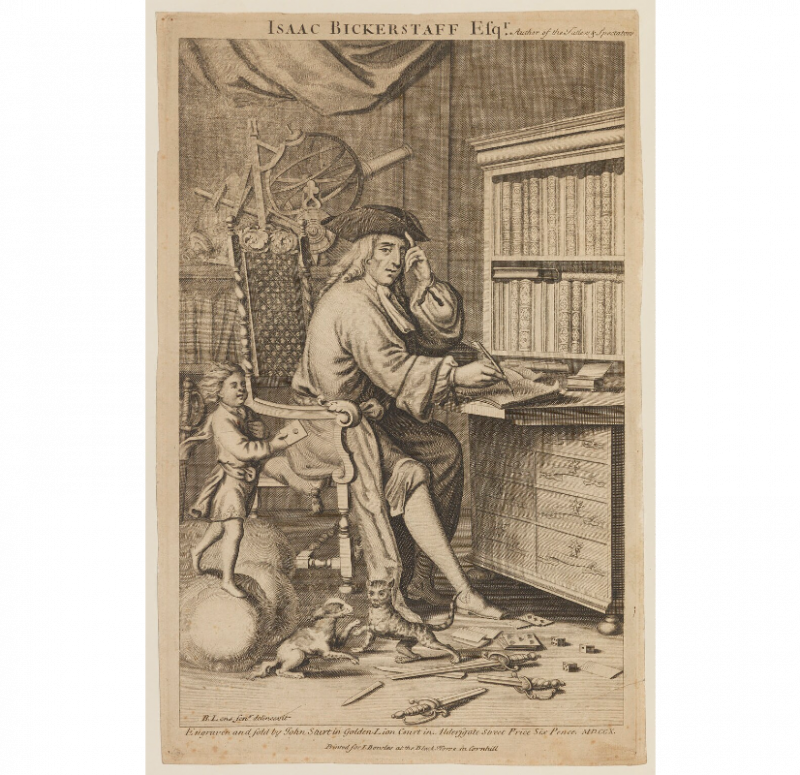

Steele made a significant contribution to the genre of the polite periodical that became key to sociable conversation both in the 1710s and throughout the eighteenth century because of the number of times his papers were reprinted. He wrote or contributed to eleven periodicals. The Tatler, which was very much Steele’s inspiration, took on the persona of Isaac Bickerstaffe, the creation of Jonathan Swift and others a year earlier (and Swift contributed to the periodical). The successful formula was to offer cultural comment (including theatre criticism, poetry and ‘gallantry’, mixed with moral guidance) in a periodical essay format, with some politics and news, lightened with humour. The paper was given a lead by Steele but involved a club of writers. Steele sought to offer instruction, particularly to male readers interested in current affairs, but also to entertain his female ones – the title was in their honour and reflected the easy chatter that the paper emulated. Indeed, the periodical genre used conversation between its invented characters as a format (it sought to have the ‘air of common speech’);5 reported conversations in the coffee houses such as Will’s and White’s; and encouraged conversation amongst its readers.

When the paper was forced to close because it had become too identified with the Whigs (and may have been the price for Steele remaining as stamp commissioner when the Tories gained power in 1710), Steele and Addison established The Spectator, which was more ostensibly impartial (though it deliberately sought to moderate heightened Tory fervour). Intrinsic to the new paper was the emulation of club sociability – ‘our Society’6 - through characters such as Sir Roger de Coverley (for Tory comments) and Sir Andrew Freeport (for Whig ones). Steele was clearly drawing on his theatrical expertise here and again frequently commented on the stage which he saw as ‘the Seat of Wit’.7 The periodical also made use of letters from readers (in one case, Steele used his own love letters to his wife),8 and therefore contributed significantly to the fashion for epistolary narratives as a vehicle for polite discussion. And the paper’s audience was explicitly the privately sociable world of post-Revolution England: he and Addison aspired to bring ‘philosophy out of closets and libraries, schools, and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea-tables and coffee–houses’.9 Readers were encouraged to set aside part of their morning to read the paper ‘as a part of the tea-equipage’.10 As this suggests, for Steele and Addison, female and male sociability overlapped (both should be virtuous and adept at conversation, and much of the periodical’s content considered love, from the perspective of both sexes), but they had different characteristics: a women’s mental and moral improvement was a good in itself but also for the enjoyment of men, to make her ‘agreeable’ in mind as well as body, for she was ‘created as it were for Ornament’.11 Men were also encouraged to be agreeable but this consisted of other qualities: ‘A Man that is Temperate, Generous, Valiant, Chaste, Faithful and Honest, may, at the same time, have Wit, Humour, Mirth, Good-breeding, and Gallantry’.12 He was also to have an apparently effortless ‘Ease in his Countenance and Confidence in his Behaviour’.13 Conversation was to be light and pleasing: ‘Men would come into Company with ten times the Pleasure they do, if they were sure of hearing nothing which should shock them, as well as expected what would please them’.14 ‘Good Breeding’ required ‘a Regard to Decency’ and disdain of vice.15 The world of Mr Spectator was, despite the inclusion of the country gentleman De Coverley, an overwhelmingly urban world where civility flourished.

- 6. Spectator 2, 2 March 1711.

- 7. Spectator 65, 15 May 1711.

- 8. Spectator 142, 13 August 1711.

- 9. Spectator 10, 12 March 1711.

- 10. Ibid.

- 11. Spectator 66, 16 May 1711; 104, 29 June 1711.

- 12. Spectator 51, 28 April 1711.

- 13. Spectator 75, 26 May 1711.

- 14. Spectator 100, 25 June 1711.

- 15. Spectator 104, 29 June 1711.

The paper is often seen as the epitome of polite sociability, a guide to how to behave and what to say - as well as what not say: issue 148, is packed with common errors in conversation and issue 155 condemned ‘an Indecent Licence taken in Discourse’ to young women.16 The paper was read long after its publication because of this – indeed for the entire eighteenth century, during which it had over seventy editions. In 1716 Dudley Ryder notes in his diary that he resolved to read certain numbers ‘with great care’, his motives apparently being to glean ‘thoughts upon gallant subjects such as are proper to entertain the ladies with’, to improve his ‘manner of thinking’ and for moral reflection.17 Habermas also saw Steele’s periodicals as helping to form the public sphere, since they helped readers to see themselves as a new kind of community, based on reason and critical discussion, thereby helping to create public opinion.18 Even so, Mr Spectator was, as his name suggests, also a semi-detached observer of society – at once both an advocate of engaging in polite sociability and a spectator of it.

- 16. Spectator 148, 20 Aug. 1711; 155, 28 Aug. 1711.

- 17. The Diary of Dudley Ryder 1715-16, ed. William Matthews (London: Methuen, 1939), p. 117, 121, 346.

- 18. Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere trans Thomas Burger with Frederick Lawrence (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), p.27, 31.

For all his reputation as a figure central to the moderating influence of The Spectator, Steele could also be a highly partisan polemicist on behalf of the Whigs (he wrote 25 pamphlets) and contributed with his pen to the political passions of the era that in many ways undermined sociability. Indeed, as proof of his divisiveness he was, on 18 March 1714, expelled from the House of Commons (to which he had been elected the previous year) on grounds of seditious libel. He returned to Parliament in 1715 and began The Englishman, another periodical with a sharp political edge attacking Tory leaders Robert Harley (now earl of Oxford) and the duke of Ormond. In 1719 Steele even fell out with his former close associate, Addison, whom he accused of forgetting his Whig principles, and himself wrote against the government in a new periodical, The Plebeian, which was politically biting. In retaliation, the government removed him from his management of Drury Lane theatre to which he was only restored once Walpole gained the ascendancy in 1721. For Steele, political passion ran in tension with polite sociability, with each feeding off the other.

Although he also often talked about ‘the people’ in his political writing, and did seek to engage a large audience, Steele’s worldview was quite exclusive. He was the voice of a bourgeois, or aspiring bourgeois, a world that (despite the title of his periodical The Plebeian which was primarily a signal of defiance against the controversial Peerage Bill which he saw as endangering the constitution by expanding the influence of the House of Lords) saw only occasional room for the mass of the people on whose labour and service polite society rested. The subscribers of the 1712-13 edition were drawn from the ranks of the aristocracy, merchants, financiers, and officeholders.19 Steele owned, through his first wife, a considerable plantation in Barbados though he had little to say about slavery beyond a story in The Spectator about a merchant who sold his ‘Indian’ lover in Barbados into slavery, even though she was carrying his child, a story that moved Steele to ‘tears’, though perhaps more because of what it said about the relations between the sexes than about the West Indian slave system.20 Although in some ways a leader of the field in politeness, he nevertheless shared many of the limiting assumptions of his contemporaries about who it was important to be sociable with. It is in part for that reason – though also, allegedly, because Addison and Steele represented an unfashionable literary engagement with the wider public rather than with arcane texts increasingly dear to academics, and lacked the ambiguity that critics craved - that in 1989 one literary critic, Brian McCrae, pronounced ‘Addison and Steele are dead’. McCrae observed that Steele was seldom taught on university syllabi, as the literary canon underwent considerable change and reconfiguration. More recent trends in cultural history, studying what John Brewer calls The Pleasures of the Imagination (1997), Lawrence Klein’s and others’ focus on politeness, and a growing interest in media history, have nevertheless gone a long way to restoring something of their once iconic status.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Bowers, Terence, ‘Universalizing Sociability: The Spectator, Civic Enfranchisement, and the Rule(s) of the Public Sphere’ in Donald J. Newman (ed.), The Spectator: Emerging Discourses (Newark: Delaware University Press, 2005), p. 155-56.

Brewer, John, The Pleasures of the Imagination (London: Harper Collins, 1997).

Cowan, Brian, ‘Mr. Spectator and the Coffeehouse Public Sphere’, Eighteenth-Century Studies (vol. 37, n° 3, April 2004), p. 345-66.

Klein, Lawrence, ‘The Third Earl of Shaftesbury and the Progress of Politeness’, Eighteenth-Century Studies (vol. 18, n° 2, 1984-5), p.186-214.

Marshall, Ashley, ‘Radical Steele: Popular Politics and the Limits of Authority’, Journal of British Studies (vol. 58, n° 2, 2019), p. 338-365.

McCrea, Brian, Addison and Steele Are Dead: The English Department, Its Canon, and the Professionalization of Literary Criticism (Newark: Delaware University Press, 1989).

Peltonen, Markku, ‘Politeness and Whiggism’, The Historical Journal (vol. 48, n° 2, 2005), p. 391-414.

In the DIGIT.EN.S Anthology

The Spectator, no. 11 (13 March 1711).

The Spectator, no. 49 (26 April 1711).

The Spectator, no. 454 (11 August 1712).