Résumé

This entry discusses the various forms of public sociability in pre-revolutionary Saint Domingue and how they became increasingly racialised. Despite European ideas about the unifying tendency of sociability, divisions existed along social, racial and gender lines. Forms of sociability discussed include dance and voodoo on plantations; the culture of maronnage; the mediating role of free women of colour in marriages and business; and the theatre. The entry shows how racialisation shaped the development of Saint-Domingue’s public sphere, setting up a clash between whites and free people of colour with the coming of the French Revolution.

As historical scholarship over the past few decades has shown, sociability played a significant role in eighteenth-century societies in Europe, especially in cities. Paris and London boasted lively public spheres as well as influential intimate ones, such as salons, where ideas, taste and politics were shaped. But did sociability also play a historically significant role in the remote French colony of Saint Domingue, on the other side of the Atlantic?

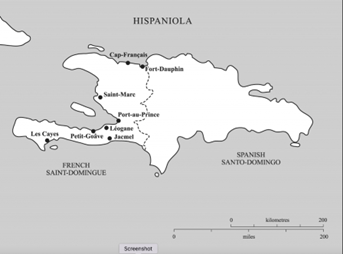

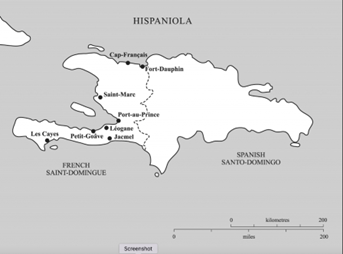

It might be thought that this slave colony had little sociability to speak of; it was known more for brutality than sociability. Nine-tenths of its population of 560,000 in 1789 was enslaved, and most inhabitants lived in the countryside. The largest city, Cap français, had only 18,550 inhabitants in 1788, and this was about three times greater than its population fifteen years earlier. Saint Domingue’s next largest city, the capital Port-au-Prince, had only 6,200 habitants in 1789, plus another 2,200 soldiers and sailors. Indeed, the colony’s entire population on the eve of the French Revolution did not even match that of Paris, which stood at 650,000 in 1789.1

- 1. Historians differ over precise numbers but not by very much. See John D. Garrigus, Before Haiti: Race and Citizenship in French Saint-Domingue (London: Palgrave Macmillian, 2006), p. 126; Fréderic Régent, La France et ses esclaves: De la colonisation aux abolitions (1620-1848) (Paris: Éditions Grasset & Fasquelle, 2007), p. 117.

European visitors and settlers generally viewed Saint Domingue as a cultural backwater. Many plantation owners (such as 40% of the sugar planters, for example) refused to live there and relied on local agents and managers (and sometimes concubines, who were often women of colour) to run their affairs.2 Those who did settle in the colony generally did so only for a few years before returning to the metropole. Creoles, who by definition were born in the Americas, were more likely to remain in the colony, though wealthy Creoles usually sent their children off to Europe for their education.

- 2. Carolyn E. Fick, The Making of Haiti: The Saint Domingue Revolution from Below (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1990), p.16; Lauren Clay, Stagestruck: The Business of Theater in Eighteenth-Century France and Its Colonies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013), p. 210.

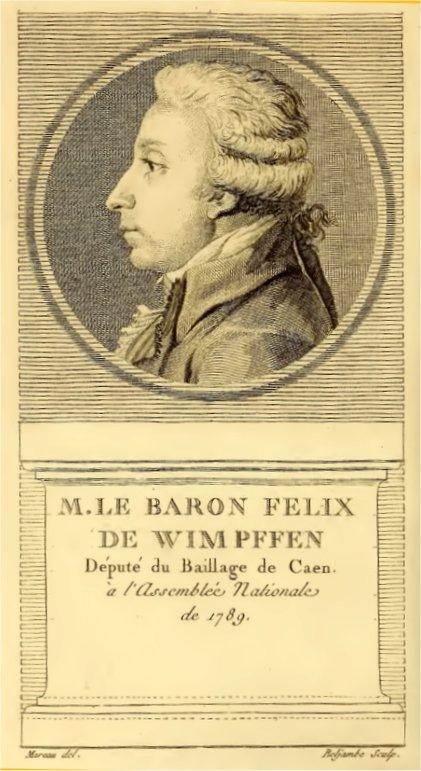

What little elite sociability there was in Saint Domingue was limited to Cap français and Port-au-Prince, and, to a lesser degree, a few other small cities. Although one contemporary referred to Cap français as ‘the Paris of our island’3 many complained about its lack of refinement: ‘Creole taste is not good taste,’ insisted the baron Wimpffen, ‘it still smells a bit of the buccaneer’ (Clay 209). Such statements expressed a narrow, Eurocentric view of what ‘society’ and sociability entailed. If we broaden those categories, we see multiple forms of sociability occurring at all levels of Saint Domingue society. An examination of these forms reveals deep tensions over race, and these tensions would explode in 1791, when the French Revolution reached the colony, and new forms of political sociability were introduced.

- 3. Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005), p. 24.

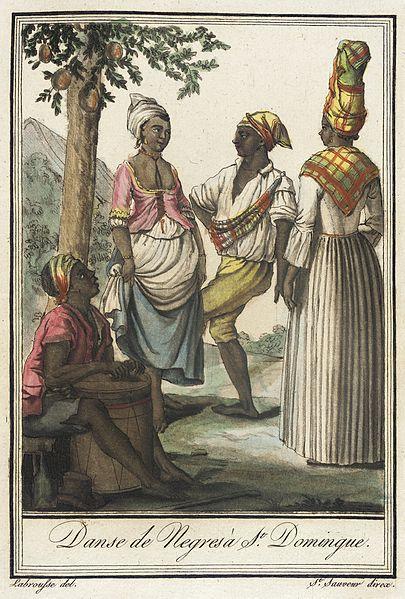

Despite the barbarism of plantation life, the enslaved people of Saint Domingue found ways to socialise – some legal, others not. Enslaved people were in some cases authorised by their owners or managers to sell the surplus from their ‘kitchen-gardens’ in nearby towns. Once there, they would pass on news and opinions to others arriving from different plantations. Information about conditions and happenings on various plantations travelled by word of mouth. Dancing, a favourite pastime, also provided occasions for enslaved people to gather. Various African traditions were combined to make spiritual, epic-like dances that told stories of ‘fear, hope, disdain, tenderness, caprice, pleasure, refusal, frenzy, evasion, ecstasy, prostration’ (Fick 40). The calenda was the most popular dance. It lasted many hours and involved people of all ages, even toddlers. Despite the ban on non-Catholic religions, voodoo, which was a religion and a dance, thrived in eighteenth-century Saint Domingue. It involved pleading with various gods to provide protection, cures and vengeance against oppressors and sometimes included animal sacrifice. The rituals sometimes took place in cemeteries that were abandoned by white people. Participants took a vow of secrecy, and despite the efforts of authorities to repress it, this form of slave sociability was never extinguished (Fick 40-45).

Marronage – departure from the plantation without permission – also involved sociability. The most common motivations to leave the plantation were to evade punishment or to seek food, since slaves were notoriously under-nourished.4 There was a wide range of the practice. Although some historians dispute the hard-and-fast categories of petit and grand marronage, there was a spectrum of the practice. Petit marronage involved leaving the plantation temporarily, often to visit friends or family, evade work or punishments, or extend holiday festivities. These maroons sometimes created networks of underground trade, exchanging foods and goods stolen from one plantation or town for those of others.5 When a maroon sought to return to the plantation, a chain of intermediaries could be involved to placate the slave owner or manager. The success in mitigating the punishment depended on the strength of the social relationships that spanned the plantation hierarchy, from slave to master (Fouchard 384). Though petit marronage was common, there is little evidence that slave owners and plantation managers much worried about it (Debien 111). There was generally a one-month grace period for an enslaved person to return without punishment. Holidays were propitious moments to return since a spirit of generosity and forgiveness tended to prevail (Fouchard 384).

- 4. Jean Fouchard, Les marrons de la liberté (Paris: Éditions de l’École, 1972), pp. 63-72.

- 5. Gabriel Debien, ‘Marronage in the French Caribbean’, in Richard Price (ed.), Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 3rd edition, 1996), p. 107-142.

Grand marronage was another matter. It was taken seriously and severely punished. It involved the definitive departure from the plantation and the forging of fugitive bands. These mostly male bands would not infrequently raid plantations for critical resources. Colonists feared not only the raids, but the spirit of defiance these maroons could spread to the enslaved populations. Voodoo, widely practiced in these communities, combined the customs, medical techniques, rituals and beliefs of various parts of Africa together with parts of Catholicism, forming a potent ideology of resistance. For at least fifty years, historians have been debating just how much the maroon communities contributed to the slave insurrections of 1791, which triggered the Haitian Revolution. Stances in this debate depend on which aspects of the phenomenon the historian chooses to focus on.6 What is clear, however, is that the hope of freedom and organisational skills developed in grand marronage were a source of inspiration for the enslaved inhabitants of many plantations, even if it was these enslaved people, rather than the maroons, who did the most to launch the 1791 insurrections, which began the Haitian Revolution (Fouchard and Fick 57).7

The place of free people of colour in colonial society was vexed and changing, but its evolution reveals the growing importance of race in structuring power relations in Saint Domingue. The number of free people of colour in 1789 almost equalled that of European whites: roughly 28,000 free coloured to 32,000 whites. Given the small numbers of white women in the colony, white men often took black women and women of colour as wives and concubines. These women were influential. Those partnered with men of wealth kept up social relations in order to marry their children into other wealthy families or to serve as intermediaries to help families pursue their marriage strategies. Some women of colour ran commercial operations in the port cities, a task that required maintaining business contacts throughout the colony. The fact that free women of colour were so well connected explains why so many European men migrating to the colony to seek their fortune took up relations with them.8

- 8. Susan M. Socolow, ‘Economic Roles of the Free Women of Color of Cap Français’, in David Barry Gaspard and Darlene Clark Hine (eds.), More than Chattel: Black Women and Slavery in the Americas (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1996), p. 279-297; Dominque Rogers and Stewart King, ‘Housekeepers, merchants, rentières: free women of color in the port cities of colonial Saint-Domingue, 1750-1790’, in Douglas Catterall and Jodi Campbell (eds.), Women in Port: gendering communities, economies, and social networks in the Atlantic port cities, 1500-1800 (Leiden: Brill, 2012), p. 257-297.

The paucity of white women in Saint-Domingue was considered a problem at the time not only because it led to interracial relationships and a ‘corruption’ of whiteness (an idea that gained ground in the late eighteenth century); it was also seen as problematic because of its cultural effects. Moreau de Saint-Méry attributed the lacklustre culture of Saint Domingue to the scarcity of white women. He wished that they would play the role that the salonnières did in Paris. But white women in the colony, he noted, tended to avoid high ‘society’ and public venues. Even if they hadn’t, it is not clear that it would have made much difference since the white colonists were not much interested in high culture anyway and preferred gambling dens, bars and dance halls, places where they might encounter women of colour and perhaps strike up sexual relations (Rogers and King 377).

Like free women of colour, free black men and men of colour also played an important role in maintaining bonds. An example of this is the black Creole and future revolutionary Toussaint Louverture. Toussaint was born into slavery but appears to have been granted freedom by 1776, when he was working as the right-hand assistant of the manager of the Bréda plantation estate. He had become renowned at a young age for his equestrian skills. His intelligence and ability to mediate between the management and the enslaved on the plantation in matters of religion (he helped proselytize for the Jesuits before 1763), medicine (he was recognised as talented in administering voodoo medicines) and business (he travelled throughout the colony managing the affairs of his superiors) was well-recognised in the colony.10 This ‘mediating’ experience helps to explain how he ended up being an effective general and leader during the Revolution.

Before the 1760s, the main fault-line running through the free population of Saint Domingue had to do with class. Race mattered, but many free people of colour could manage to attain wealth and status. They even appeared as white in many legal documents, despite regulations requiring race to be indicated dating back to the Code Noir of 1685. Their success and influence were especially pronounced in the remote southern and western parts of the colony, where a frontier-type economy facilitated the rise of mixed-race Creoles. By the late 1760s, however, this group was increasingly targeted by racist discourses and policies. An ideology of white superiority, rooted in the scientific and moral literature on race emerging in Enlightenment Europe, trickled into colony.

- 10. Sudhir Hazareesingh, Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture (New York: Picador, Farrar and Giroux, 2020), p. 19-40.

The ideology was seen as useful to white authorities seeking to resolve what they took to be ‘problems’: it helped them assuage the growing number of petits blancs arriving from France, who, though they also hated the wealthy whites, bristled at the higher status of the wealthy Creoles of colour. The ideology of white superiority also provided a rationale for discouraging sexual relations between white men and women of colour by demonising the latter as inferior, impure and dangerous to the integrity of white ‘Europeanness’.11

- 11. Garrigus, Before Haiti, p. 141-170; Trevor Burnard and John Garrigus, The plantation machine: Atlantic capitalism in French Saint-Domingue and British Jamaica (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), p. 164-191.

The new policies motivated by white superiority included the requirement of free people of colour to abandon their European surnames and replace them with African ones. The sumptuary regulations of 1779 forbade free people of colour ‘from affecting in their clothing, hairstyles, apparel or adornment, in an objectionable assimilation with the ways that white men and white women dress themselves.’12 Free men of colour were restricted from working in law and medicine and could no longer serve as officers in the militias, which they were now obliged to enrol in. Not all of these restrictions were rigorously enforced. Nor was the ability of free people of colour to buy, sell and bequeath property compromised, as it had been in British Jamaica since the 1760s (Burnhard and Garrigus 151-152). In fact, many people of colour became wealthier in the 1780s (Garrigus 171-194). But it was in certain forms of sociability coming from Europe, and most notably the theatre, that the racial hierarchy and intolerance was made visible in the public sphere.

- 12. Nicole Willson, ‘Sartorial insurgencies: Rebel women, headwraps and the revolutionary Black Atlantic’, Atlantic Studies, (vol. 19 n° 1, 2022), p. 86-106.; Stewart King, Blue Coat or Powdered Wig: Free People of Color in Pre-Revolutionary Saint Domingue (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017).

Amateur performance of plays had long been a pastime in Saint Domingue. It was source of entertainment among family and friends. Performing European plays helped the colonists feel connected to the Continent. Enthusiasm for theatre grew along with urban populations. Theatre houses sprang up in Cap français and Port-au-Prince in the 1740s. By the 1760s, Le Cap boasted a theatre large enough to accommodate 1500 spectators. A decade later, it was staging performances three times a week – a sign of the importance of this institution for the city and surrounding region. By the 1780s, the smaller cities of Léogâne, Les Cayes, Jérémie and Saint-Marc all had theatre houses.13 Theatre had become an ostentatious place of colonial sociability. People attended not only for the entertainment but also to conduct business.14

For many, the theatre was the only site of sociability in the colony. ‘Deprived of the [Parisian] promenade’, one journalist wrote in 1786, ‘we have only the theatre as a public meeting point.’15 Despite the opening of some bookstores, coffeehouses and dance halls after the 1770s, the celebrated observer of colonial life, Moreau de Saint-Méry, believed ‘it would be impossible to do without a theatre in Le Cap. We have little society in this city, and there we are at least gathered, though perhaps not united’ (Clay 214).

Theatre was also, as Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler have argued for a different colonial context, a place where white colonists ‘fashioned their distinctions’ and ‘conjured up their whiteness’ (Clay 198). Whereas free people of colour in the countryside had often been able to overcome the racism that defined the colony’s culture by cultivating business relationships over time and accumulating wealth and status, the theatre did not offer such manoeuvrability. Even before the theatre doors were thrown open, decisions about accessibility and seating had to be made. ‘Race’ provided the framework for making those decisions. The financial viability of theatres, which were prone to bankruptcies despite their popularity (actors and building maintenance were expensive), necessitated large audiences and therefore, inclusivity. But admitting individuals on a colour-blind basis was considered problematic in a society built on racial distinctions.

- 15. The quote appeared in the ‘Affiches, annonces et avis divers’ by Mozard; see Laurence Marie, ‘Writing about Theatre in Saint-Domingue (1766-1791): a Public Voice on a Public Space?’, in Jeffrey M. Leichman and Karine Bénac-Giroux (eds.), Colonialism and Slavery in Performance: Theatre and the Eighteenth-Century French Caribbean (Oxford: Oxford University Studies in the Enlightenment, 2021), p. 155.

Unsurprisingly, enslaved people were banned from attending the theatre. The only exceptions were the servants of wealthy spectators and the black musicians that masters occasionally hired out to the orchestra (Clay 196). Enslaved people depicted on stage were often whites with blackface.16 Free actors of colour, however, were known to take the stage, and some, such as ‘Minette’ (stage name for Elisabeth Alexandrine Louise Ferrand), became local stars. Spectators of colour were another matter. They were confined to the rear floor of the amphitheatre in Cap français. Those of colour who were wealthy enough to subscribe to boxes found them situated at the very top of the theatre; three were reserved for free people of colour, three for free blacks, and the rest for ‘mulattoes’ (Bubois 24). Mothers and daughters sometimes had to sit in different sections of the theatre according to their status and skin.

Viewed together, the various forms of sociability in Saint Domingue – from the plantation and mountain maroon communities, to the business networks of free people of colour, to the theatre houses of Cap français and Port-au-Prince – reveal the depth of racial tensions brewing in the colony. These tensions would explode once the French Revolution, and political sociability, arrived after 1789. Were free people of colour to be allowed to gather in political assemblies to participate in the self-governance of the colony? Was an economic system based on racial inequality compatible with the principles of the French Revolution? The patterns of sociability of Ancien Régime Saint Domingue did not offer clear answers to these questions. To the contrary, those patterns foreclosed any peaceful consensus on how to answer them.

- 16. Julia Prest, ‘Pale imitations: White performances of slave dance in the public theatres of pre-revolutionary Saint-Domingue’, Atlantic Studies (vol.16, n° 4, 2019), p. 502-520.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Dubois, Laurent and Karine Bénac-Giroux, Colonialism and Slavery in Performance: Theatre and the Eighteenth-Century French Caribbean (Oxford: Oxford University Studies in the Enlightenment, 2021).