Résumé

This entry shows how Richardson, through his writing and reading practices, fashioned links with his readers and created a society of writers and readers based on esteem, admiration and friendship, thereby promoting a special kind of sociability, relying on the qualities of the heart and mind.

Mots-clés

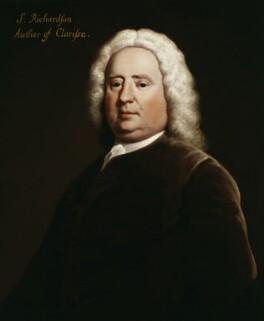

Although Samuel Richardson was a reserved, taciturn man who was ill at ease in society and preferred indirect means of communication – notes and gestures – to direct communication through spoken words, his writing activity enabled him to promote sociability through the creation of a society of writers and readers. For one thing, in his Familiar Letters1 , he gave his readers practical advice on how to become a sociable people and behave as such, what company to choose, how to find subjects of common interest in conversation, and how to respect turn of speech so that every participant might enjoy the pleasures of conversation. For another thing, the interplay takes place between real and fictional letters as Richardson’s three novels are – partly in the case of Pamela; Or, Virtue Rewarded, and wholly in the case of Clarissa; Or, the History of a Young Lady and The History of Sir Charles Grandison – epistolary novels.2 A network of sociability is fashioned by the very acts of sending and receiving letters, especially as during the eighteenth century people often lent to others the letters that had been sent to them or gathered to hear someone read letters they had received, thereby revealing a move from single reader to multiple readers or listeners, and an expansion promoting sociability and the development of a social network.3 Letters create a vital link between people and sometimes also are the first link in a chain of sociability that begins with the writing of the letter, and develops through its reading, potentially paving the way for real meetings between the correspondents.

Even though at first sight direct communication and orality are the best ways available to establish sociable links, Richardson and some of his correspondents, among them Lady Bradshaigh4 , considered that there were advantages to writing and drawbacks to speaking because some remarks are made more to be written than spoken, and because speaking can lead to shallow communication. On the contrary, writing, especially when it manages to integrate features typical of orality such as direct speech, so that the letter takes the form of a dialogue, promotes relationships founded on depth and reflection, as well as friendship based on authenticity, or, in Richardson’s words, a contract sealed between the hearts of the parties concerned:

‘Correspondence is, indeed, the cement of friendship: it is friendship avowed under hand and seal, friendship upon bond, as I may say: more pure, yet more ardent, and less broken in upon, than personal conversation can be even amongst the most pure, because of the deliberation it allows, from the very preparation to, and action of writing [...]‘5

- 1. Samuel Richardson, Familiar Letters (London: C. Rivington, 1741; 4th ed., 1750). Cambridge, Chadwyck-Healey, Eighteenth-Century Fiction Full-Text Database, 1996.

- 2. Samuel Richardson, Pamela; Or, Virtue Rewarded (London: C. Rivington and J. Osborn, 1740); Clarissa; Or, the History of a Young Lady, ed. Angus Ross (London: S. Richardson, 1747-1748); The History of Sir Charles Grandison (London: S. Richardson, 1754).

- 3. The same move from private to public (and publication) takes place in Pamela, as is analysed by Janet Gurkin Altman: ‘If, in the first half, B is Pamela’s principal reader, in the second half, her audience multiplies. First B’s sister, Lady Davers, then Lady Davers’s friends read her letters; ultimately the letters are circulated among an even wider public. This ‘publication‘ of Pamela’s story is consonant with B’s general efforts to make a spectacle of Pamela in other ways, by having her tell stories in salons and even reciting himself one of her poems before a group of guests. […] The movement from the first half to the second half of Richardson’s novel is the movement from the privacy of the prison and the tête-à-tête to the world of society and the salon, the movement from private reading to publication.’ Epistolarity: Approaches to a Form (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1982), p. 105-106.

- 4. Lady Bradshaigh wrote to Richardson, ‘I could not express half my thoughts when I saw you last.’ The Correspondence of Samuel Richardson, author of Pamela, Clarissa and Sir Charles Grandison, ed. Anna Laetitia Barbauld (London: Phillips, 1804), 6 vols, VI, p. 1. Hereafter, Correspondence.

- 5. Correspondence, III, p. 245. Significantly, about his relationship with Miss Mulso and Miss Prescott, Richardson writes, ‘the pen and ink […] have furnished the cement of our more intimate friendship’ (Correspondence, IV, p. 110-111). On the integration of features typical of oral discourse into letters, see Robert A. Erickson, The Language of the Heart, 1600-1750 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997).

The consequence of the process is to fashion and enhance epistolary sociability, and it is no wonder that the images, similes and metaphors the novelist and his correspondents use should unite writing and talking, as where Lady Echlin mentions their ‘pen-conversation’ (Correspondence, V, 52), where Richardson reveals to Sophia Westcomb how much he enjoys ‘the converse of the pen’ (Correspondence, III, 246) and to Miss Mulso that he likes ‘talking with my pen to [her]’ (Correspondence, III, 197), and where Richardson’s friend Thomas Edwards acknowledges that ‘to be loquacious upon paper […] is the only way a solitary man can talk’ (Correspondence, III, 80).

As a result, oral and epistolary sociability appear to be complementary notions, as is also revealed by the fact that epistolary exchanges are often a prelude or a follow-up to physical encounters, as past visits regularly give rise to very friendly letters where future visits are organized or announced (Correspondence, II, 295). As a precious link between writer and addressee(s) and as a means of fighting loneliness and exclusion, letters thus promote sociability.

Conversely, silence and lack of answer to a letter are a threat to friendship and sociability, showing that if they are to live on, feelings between writer and addressee(s) need to be constantly kept going. Yet, at the same time, letter-writing necessitates privacy, as Richardson explains when he writes to Sophia Westcomb: ‘the pen is jealous of company. It expects […] to engross the writer’s whole self; everybody allows the writer to withdraw: it disdains company; and will have the entire attention’ (Correspondence, III, 247).

The main topic that unites Richardson with his correspondents is discussions on the contents of his epistolary novels, and one of the aims of the novelist is to give rise to discussions or debates about his characters or the plots of his novels. Such exchanges were all the more important to the novelist as he sometimes asked his correspondents to provide him with scenes for his novels, especially as regarded scenes among characters belonging to the highest classes of society, to which he himself – as a middle-class man – did not belong (Correspondence, IV, 71). Very eager to receive help on scenes in high life, Richardson nevertheless refused to close Clarissa with a happy ending – a wedding between his heroine and Lovelace – although several friends of his had asked him to save Clarissa. Among them were Lady Bradshaigh and Lady Echlin, the latter going so far as to write An Alternative Ending to Richardson’s Clarissa.6

- 6. Lady Elizabeth Echlin, An Alternative Ending to Richardson’s Clarissa, ed. Dimiter Daphinoff. Schweizer anglistische Arbeiten, vol. 107. (Bern: Francke Verlag, 1982).

Even though Richardson’s epistolary friends did not always agree as to the development of his plots and the treatment of his characters, they shared the same values, which provided the fundaments of their epistolary sociability, and novelistic tastes and references. All Richardson’s epistolary friends are characterized by a profound admiration and respect for the novelist’s talent and moral outlook, and they came to judge people according to their appreciation of Richardson’s novels, especially Clarissa, often used as a moral and sentimental yardstick.7 In the circle of Richardson’s epistolary friends, social elitism and gender boundaries were therefore transcended and replaced by an elitism based on intellectual, moral and sentimental values that consecrate true merit, essential worth and the noble qualities of the heart and mind, through which one is able to appreciate Richardson’s novels, or in Tom Keymer’s words, the ‘community of the feeling heart’.8 The members of this family-like community were particularly happy when they could gather around Richardson, who read to them passages from his novels in North End, the novelist’s residence in London, which acted as a magnet attracting letters and visitors, thereby promoting sociability.9

- 7. This is illustrated for instance by Thomas Edwards’s consideration of Clarissa as ‘a touchstone by which I shall try the hearts of my acquaintance, and judge which of them are true standard’ (Correspondence, III, p. 3).

- 8. Tom Keymer, Richardson’s Clarissa and the Eighteenth-Century Reader (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 203.

- 9. Significantly enough, Richardson called Miss Mulso the ‘child of [his] heart’ (Correspondence, III, p. 191) and Lady Bradshaigh ‘the daughter of [his] mind’ (Correspondence, II, p. 101), and William Strahan wrote to the novelist: ‘I esteem you as my friend, my adviser, my pattern […] I love you as my father’ (Correspondence, I, p. 138).

Partager

Références complémentaires

Altman, Janet Gurkin, Epistolarity: Approaches to a Form (Columbus: Ohio State University, 1982).

Castle, Terry, Clarissa’s Ciphers. Meaning and Disruption in Richardson’s Clarissa (New York, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982).

Keymer, Tom, Richardson’s Clarissa and the Eighteenth-Century Reader (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Keymer, Thomas and Sabor, Peter, ‘Samuel Richardson’s Correspondence: Additions to Eaves and Kimpel’, Notes and Queries (vol. 50, 2003), p.215-218.

Lesueur, Christophe, ‘Poétique et économie de la communication dans Clarissa de Samuel Richardson‘ (Thèse, Université Toulouse 2-Le Mirail, 2011).

Mullan, John, Sentiment and Sociability. The Language of Feeling in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988).

Sabor, Peter, ‘'The Job I Have Perhaps Rashly Undertaken': Publishing the Complete Correspondence of Samuel Richardson’, Eighteenth-Century Life (vol. 35, n° 1, 2011), p. 9-28.

In the DIGIT.EN.S Anthology

Samuel Richardson, Clarissa (1748), Letter LV.

Samuel Richardson, Clarissa (1748), iii, p. 42-4.