Résumé

How individuals managed solitude, used their time alone productively, and made the transition between solitude and sociability in their daily lives were topics continuously addressed in writings from the long-eighteenth century. There was no vocabulary for loneliness in this period, but solitude was a state often associated with melancholy and thus frequently employed in a negative sense. A range of eighteenth-century writers warned about the effects of social isolation on spiritual, physical, and mental wellbeing. Yet, for all its challenges, solitude could also act as an important remedy for negative social interactions and a useful means of enhancing individual sociability. Sociability and solitude could thus be highly complementary of one another.

Mots-clés

In 1711 Joseph Addison spoke of his vision for his new periodical, The Spectator. In his desire to entertain and instruct, he sought to bring men and women out of closets ‘to dwell in Clubs and Assemblies, at Tea-tables, and in Coffee houses’.1 Like many of his contemporaries, he believed that sociability was both natural and necessary for civil society. The eighteenth century was a culture built on the ideals of company, association, and politeness, where men and women were expected to maintain a careful balance between engagement and seclusion in their everyday lives. How much time an individual was expected to spend alone and in company remained a matter of much debate and controversy throughout this period. Those who chose to devote (or advocate) lengthy periods of time in isolation seemed to flout the moral codes and good manners that lay at the heart of sociability. Exploring how solitude was experienced and debated challenges our understanding of the benefits of sociability from this period.

- 1. Spectator 10, 12 March 1711.

In classical Latin solitudo was most often employed in a negative sense. It denoted a place or condition and thus a physical state of isolation that stood at odds with the ideal of civilisation that brought with it the benefits of mutual support and protection. The distinct word ‘lonely’ appeared in the English language only in the early seventeenth century, yet, as Diana Webb argues, it was barely distinguishable in meaning from ‘solitary’.2 People were alone, but this was a physical rather than emotional state. Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary (1755) emphasised the physical dimensions of solitude: living a ‘lonely life’, being remote from company and also ‘a lonely place. A desert’.3 But it was not until the nineteenth century, argues Fay Bound Alberti, that a concept for feeling ‘lonely’ in a sense familiar to us – as a state of being either temporarily or permanently alone – entered the English vocabulary.4

- 2. Diana Webb, Privacy and Solitude in the Middle Ages (London & New York: Continuum, 2007), p. xv.

- 3. Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language (London, 1755), entry for ‘Solitude’.

- 4. Fay Bound Alberti, A Biography of Loneliness: The History of an Emotion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 16.

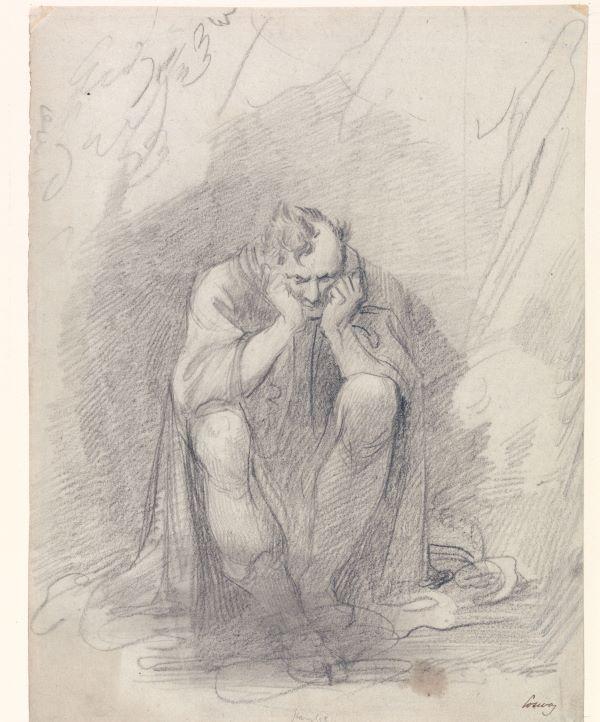

The connotations of being alone, however, were often negative, especially in the seventeenth century. The absence of company was widely recognised to adversely affect spiritual, mental, and physical health. The frontispiece to Robert Burton’s seminal work, The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), explicitly linked solitude and melancholy, with a visual depiction of solitude. Here, solitude was represented through images of a natural environment – with deer, hares and other animals – devoid completely of people. He described those who engaged in voluntary solitude ‘to walke alone in some solitary grove, betwixt wood and water’ as men who ‘degenerat from men, and from sociable creatures, [to] become beasts, monsters, inhumane, ugly to behold, Misanthropi: they do even lothe themselves, & hate the company of men’.5

- 5. Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy (Oxford, 1621), p. 117.

Aside from the lack of humanity associated with nature, one of the major kinds of melancholy that Burton associates with solitude was religious melancholy, where sociability was not an obvious cure. The relationship between solitude and religion was complex. For some, this overwhelming sense of aloneness might stem from a state of spiritual despair that they had been abandoned by God. Yet solitude was the favoured place in which to achieve a higher connection to the divine. This was common in the monastic and cloistered cultures of Catholicism. Many zealous Protestants also delighted in regular retreats into the closet or other private spaces to meditate and pray in a space separate from secular concerns. Yet the act of isolating oneself from company, even for spiritual retreat, was regarded by many English Protestants as a repulsive and selfish act. It was viewed as a breach of Christian duties, where pious individuals had a responsibility to contribute to the spiritual welfare of the wider community rather than isolate themselves from it. Richard Baxter, for instance, in his treatise Converse with God in Solitude, first published in 1664, identified not the pleasures of solitude, but the ‘pride and self-ignorance’ of those willing to elevate themselves above the conversation of others. Baxter warned that ‘many are led into solitude by their infirmities or vices’, noting that ‘popish vanity may seduce them ... [to] imagine, that they are serving God and entering into perfection, when they are but obeying their sinful inclinations’.6 The Godly Christian, he argued, had a duty to work with the sinful society that surrounded him and not to withdraw from it for his own spiritual edification.

- 6. Richard Baxter, Converse with God in Solitude: Or, The Christian Improving the Insufficiency and Uncertainty of Human Friendship, for Conversing with God in Secret, abridged by Benjamin Fawcett (2nd edition, 1774), p. 32.

The devil inhabited even the most sanctified of spaces, and without the support of others it was recognised that the solitary individual risked temptation. Solitude provided the ideal conditions for sin and impure thoughts and desires to emerge. A favourite quotation on this subject came from Ecclesiastes 4:10: ‘Woe to him who is alone, for there is none to pick him up if he should fall’. Physical solitude did not, on its own, offer spiritual revelation or absolute protection from sin. Even in non-religious writings, it was widely recognised that the decision to remove oneself from the company did not come without its consequences. This view was heavily indebted to the ethics of Aristotle and Plato, and the teachings of Cicero and the Stoics, who all emphasised civic society above the individual. The dominant view among secular writers was that man was a greater enemy to himself than he was to others, and that his efforts were better pursued in active public life. A familiar account to many readers of didactic literature from this period was that of Diogenes of Sinope, who warned a young man walking alone and ‘discoursing with himself’ to ‘Take Heed ... that thou Converse not with thine Enemy’.7

- 7. N. H., The Ladies Dictionary; Being a General Entertainment for the Fair-Sex (London, 1694), p. 73.

The dangers of solitude persisted well into the eighteenth century and are subtly conveyed in Samuel Richardson’s celebrated 1748 epistolary novel Clarissa, Or, the History of a Young Lady, which has been characterised as ‘a tragedy of solitude, inarticulacy and deceit’.8 Like friendship, solitude in the troubled world of Clarissa, did not follow its expected course. Throughout the novel, but especially at the start, Clarissa found comfort in her private closet and in writing to her friends, especially her confidante, Anna Howe. Her closet was a space where she was able to physically exclude herself from her cruel and overbearing family and enabled her, as Karen Lipsedge suggests, ‘to possess, control, and mediate her own space’ and thus to ‘maintain her inner self’.9 Yet in seeking retreat from the people around her, the time she spent in the unregulated space of her closet came to have destructive consequences since it provided Clarissa with the opportunity to engage in secret correspondence with the villainous Robert Lovelace, who would eventually bring about her demise.

- 8. Tom Keymer, Richardson’s ‘Clarissa’ and the Eighteenth-Century Reader (Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 225.

- 9. Karen Lipsedge, ‘‘Enter into thy Closet’: Women, Closet Culture, and the Eighteenth-Century English Novel’, in John Styles and Amanda Vickery (eds.), Gender, Taste and Material Culture in Britain and North America, 1700‒1830 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006), p. 119‒20.

The depiction of solitude in Richardson’s tragic novel reflected the complex ways in which early modern women encountered, described, and understood their physical and social isolation. It reflects at once an impulse to retreat from a busy and overbearing domestic situation, whilst also underscoring a wider concern that young women may ‘misuse’ the private space and time they had been granted. Implicit within Richardson’s tragedy, and in the wider conduct literature from this period, was the question of whether solitude was suited to women at all. Indeed, many contemporary discussions of solitude excluded women from the benefits of solitary retreat. The display of virtues achieved in solitude were believed to be uncommon among women. Regarded as the naturally more sociable sex and unsuited to lengthy periods of time alone, very few printed and didactic texts explored the possibility that women might spend time in solitude or solitary contemplation. A female contributor to The Spectator noted in 1711 that ‘We [women] must have company [...] Solitude is an unnatural Being to us’.10

At a time when society was becoming increasingly socially orientated and structured around companionable pursuits, it is easy to conclude that solitude was a simple antonym of physical company. There are, however, significant links between these two states, most obviously because one of the most common activities conducted in solitude was letter writing. This was an activity with which both men and women could engage with the explicit intention of creating sociability and strengthening personal connections. A quiet place and spare time in the day were prerequisites for writing well-crafted and thoughtful letters.

- 10. Spectator, 159, 31 August 1711.

Moreover, for all the challenges that solitude might bring, it invariably provided space for contemplative activities, many of which enhanced individual sociability, for example by furnishing men (and women) with conversation pieces. Dudley Ryder described multiple instances in his diary where he had read a specific text for the purposes of improving his conversation. In July 1715, for instance, he described how ‘it is very useful to be acquainted with books that treat of characters’, for ‘[n]othing fits a man more for conversation’. He described the pleasing nature of the conversation he had with his cousin Joseph Billio, ‘because we can fall into subjects that are speculative and philosophical and are not confined to matters of fact to entertain one another’. By contrast, he noted the difficulties he had conversing with her sister for she ‘not having been used to reading her knowledge is confined within the compass of a very few things, that it is very difficult to maintain a conversation with her for any time’.11 Ryder’s derisory comments about his sister’s lack of knowledge underscore the gendered implications of solitude at this time.

- 11. William Matthews (ed.), The Diary of Dudley Ryder, 1715–1716 (London: Methuen, 1939), p. 45, 50, 81.

Having time away from company was often regarded as a remedy to potentially negative and damaging social interactions. It was also a means of enhancing one’s individual sociability. The Earl of Shaftesbury, for instance, viewed introspective self-inquiry as essential for retaining a sense of self within what might otherwise be overwhelming and harmful social interactions, and so emphasised the necessity of withdrawing from company in order to advance civility and facilitate emotional restraint. As Lawrence E. Klein’s study of Shaftesbury’s notebooks has shown, he was inclined to avoid social contact, since interaction with the world was harmful and ‘one might only be able to constitute oneself as a substantial character in retirement and privacy’.12 The French philosopher Michel de Montaigne, also spoke of how time spent alone represented not retreat, but a chance to ‘stretch and expand outward’. As he noted: ‘I throw myself into affairs of state and into the world more readily when I am alone’.13 Characterising retreat and reflection as an enhancement to other types of sociability, justified men’s and women’s decisions to withdraw from company, an act that might in other circumstances be perceived as rude.

- 12. Lawrence E. Klein, Shaftesbury and the Culture of Politeness: Moral Discourses and Cultural Politics in Early Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. 79, 85.

- 13. Michel de Montaigne, ‘Of Three Kinds of Association’ in The Complete Works: Essays, Travel Journal, Letters, transl. Donald M. Frame (New York: Everyman, 2003), p. 750.

The types of solitary individuals took many forms at this time. One of the most noteworthy was the hermit, almost always male, who had chosen to forsake social interaction and live completely in isolation. The hermit was a recurring trope in the literature of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This included the melancholy Jaques in Shakespeare’s As You Like It, who despised the world and wished to leave it behind, preferring amusements for his mind rather than body.14 There were also accounts of real-life hermits, like the popular relation of Roger Crab. His decision to give up his haberdashery business in London and shun all company was made all the more remarkable by his unusual lifestyle, especially his decision to become a vegetarian, ‘refusing to eat any sort of flesh [...] or to drinke any Beer, Ale, or Wine’.15 In the eighteenth century, the figure of the hermit had become so central to cultures of sociability and literature that there were even accounts of hermits being employed as ornaments in the gardens of English estates. Sir Richard Hill’s estate in Hawkstone in Shropshire, for example, was the summer residence of Father Francis a ‘solitary sire’, who was described as being found ‘generally in a sitting posture, with a table before him, on which is a skull, the emblem of mortality, an hour-glass, a book and a pair of spectacles’.16

- 14. William Shakespeare, As You Like It, First Avenue Editions (Minneapolis : Lerner Publishing, 2015), p. 40–2, 65–6.

- 15. Anon., The English Hermite, or, Wonder of This Age Being a Relation of the Life of Roger Crab, Living Near Uxbridg (London, 1655), p. 1.

- 16. Quoted in Gordon Campbell, The Hermit in the Garden: From Imperial Rome to Ornamental Gnome (Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 1.

So, was there a place for solitude in the heightened culture of sociability in the long eighteenth century? Certainly, deliberate retirement often stood in tension with the ideals of politeness that stood at the heart of this heightened culture of collaboration and collective endeavour. However, its practice was increasingly viewed in a positive sense over the course of the eighteenth century. Indeed, solitude had many different meanings and applications for different people at this time. While we assume that a solitary individual, or one who happens to be alone, feels lonely, the experience of solitude in the eighteenth century also enabled men and women valuable space and opportunities to enhance their personal sociability. It was as much a mental as a physical state. In many ways, the oscillation between the extreme melancholy generated by intense feelings of isolation could be countered by the decision to find the time and space to withdraw in profitable retreat from bad or frivolous company. ‘To retire is the best Improvement of Solitude’, the former diplomat Richard Bulstrode declared in 1715, ‘and to be thus Alone is the way to bring us to the most desirable Company’.17

- 17. Richard Bulstrode, Miscellaneous Essays (2nd edition, London, 1724), p. 94.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Alberti, Fay Bound, A Biography of Loneliness: The History of an Emotion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Enenkel, Karl A. E. and Göttler, Christine (eds.), Solitudo: Spaces, Places, and Times of Solitude in Late Medieval and Early Modern Cultures (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2018).

Hannan, Leonie, Women of Letters, Gender, Writing and the Life of the Mind in Early Modern England (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016).

Mattison, Andrew, Solitude and Speechlessness: Renaissance Writing and Reading in Isolation (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019).

Shapin, Steven, ‘’The Mind Is Its Own Place’: Science and Solitude in Seventeenth-Century England’, Science in Context 4, (vol. 4, n° 1, 1990), p. 191‒218.

Snell, K. D. M., ‘The Rise of Living Alone and Loneliness in History’, Social History (vol. 42, n° 1, 2017), p. 2-28.

Taylor, Barbara, ‘Rousseau and Wollstonecraft: Solitary Walkers’, in Helena Rosenblatt and Paul Schweigert (eds.), Thinking with Rousseau: From Machiavelli to Schmitt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), p. 211‒234.

Vincent, David, A History of Solitude (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020).

In the DIGIT.EN.S Anthology

Samuel Richardson, Clarissa. Or, the History of a Young Lady: Comprehending the Most Important Concerns of Private Life (3 vols, 1748), iii, p. 42-4.