Résumé

Spa towns encompass various sizes and categories in eighteenth-century Britain. The role of health and medicine pervades social interactions in spa towns which abounded in urban spaces dedicated to sociability: the pump-room, the assembly rooms, the walks, villas and salons. Time was also structured socially through the seasons and the daily schedules: from dawn to dusk spa societies were regulated by the emblematic figure of the master of ceremonies. The entry ends on a more recent historiographical idea on the role of gender in spa societies, and their specificities as a place for soft politics.

Mots-clés

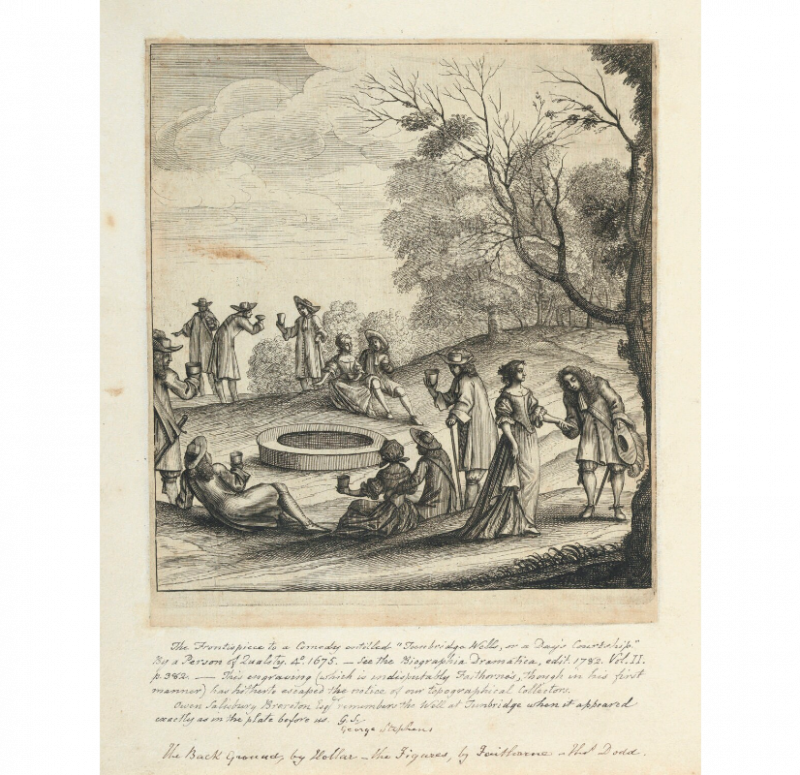

Because of their seasonal structure, spa towns are a lens onto the modes of eighteenth-century sociability. In greater spa towns, the pump-room and baths opened only in the spring and summer, during which the sick came for a limited amount of time to drink or bathe in the waters, depending on their medical prescription and the treatment available on site. Such seasonal time created ephemeral micro-societies which provided a break from the otherwise equally ritualized rhythm and social dynamics of both urban and rural life. Monitored by a master of ceremonies for the most important spa towns such as Bath, Tunbridge Wells, Buxton, Harrogate, Moffat, Scarborough or Cheltenham, the scheduled activities of the spa resulted in literary productions which mirrored and satirized the social life of spas.1 This proto-touristic sociability mingled with the social structure of the towns that were comparable to market-towns provided with an exceptional amount of inns, doctors, and paid care providers (doctors, bath women, porters &c.). In smaller-sized spas, however, social life was less seasonal and less regulated, as regional and local visitors came to take the waters all year round. Nonetheless, smaller spas and spa towns partook in the monitoring of sociability by investing in urban planning and to various degrees, providing specific spaces for the sick to meet, exercise, and take the waters.

Although spa-towns were more developed on British soil, the use of healing waters was not restricted to the mainland: mineral waters were also taken in early America and Jamaica. In 1784, Thomas Dancer published A short Dissertation on the Jamaica Bath Waters in which he considers the ‘powerful remedy' against the ‘prevailing diseases of the climate.’ Much remains to be written on the sociable encounters in Jamaican spas such as the Bath waters near St Thomas, and the interactions between natives, colons and enslaved people around the use of therapeutic waters. In America, Charlene Lewis has shown the ways in which planter sociability at Virginia Springs was inherent to the construction of a planters’ culture in the South of the United States at the turn of the century. Earlier in the century, spas like Saratoga Springs were investigated by doctors and detached from the use made by Native American hydrophilic cultures, as Vaugh Scribner explains, though the phenomenon was not as widespread as it was in Britain.2 In England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland, more than 300 spas were recorded throughout the century – yet ‘spa’ was an umbrella term in the eighteenth-century English language.3

- 1. See Peter Borsay, The image of Georgian Bath, 1700-2000: towns, heritage, and history (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 200, pp. 30-32.

- 2. Charlene M. Boyer Lewis, Ladies and Gentlemen on Display: Planter Society at the Virginia Springs, 1790-1860. University of Virginia Press, 2001; Vaughn Scribner, ‘‘The Happy Effects of These Waters’: Colonial American Mineral Spas and the British Civilizing Mission’, Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 14, no. 3 (July 25, 2016), pp. 409–49; Karl Wood, ‘The Spa as Sociable Space: A Comparative View of Baden-Baden and Saratoga Springs’ in La Représentation et la réinvention des espaces de sociabilité au cours du long dix-huitième siècle, ed. Annick Cossic-Péricarpin & Emrys Jones (Paris : Le Manuscrit, 2021), pp. 301-329.

- 3. See the regional maps in the appendix to Sophie Vasset, Murky waters: British Spas in Eighteenth-Century Medicine and Literature (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022).

Social spaces for the sick

The pump-room, a central feature of spa towns, was built around the pump which extracted the water from the well or spa, and the minerals waters were drafted from the tap and distributed to the sick visitors who came to drink them at hours prescribed by their water-doctors. Pump-rooms were often large enough to enable people to walk so as to make the waters pass, all the while entertaining free conversation and meeting with other visitors. Sociability was therefore intrinsically connected to health-care: the spa’s primary meeting space was marked by health and sickness and spa towns were, as Annick Cossic writes, ‘invalid-friendly’.4

Many visitors were sick, and taking the waters was considered a respectable and potentially efficient treatment, part of the pharmacopeia for patients and doctors alike – sickness, therefore, should not be seen as a pretext to visit spa towns but as the primary reason for taking the trip.5 Many water doctors came for the season even if some lived in a market-town nearby, and more than 200 water treatises were published throughout the eighteenth-century, analysing the waters, exposing a variety of successful cases, and all agreeing on one point that underlined the therapeutic process through its concern for side-effects: the waters were potentially dangerous and had to be taken carefully and gradually, under the prescription and close monitoring of a physician. Yet, the relationships between patients and their circles, who advised each other on which waters to take, shows that care and health-related advice was inscribed in the sociable interactions of the middle and upper class. In parallel, the regular complaints of doctors on the poor commoners and their unmonitored drinking in excess, entailing dangerous purges, shows the diversity of visitors who came to take the waters. Some wells even had restricted access while the very status of water, a common resource, raised the question of accessibility. In some spa towns, the care of the poor was undertaken by charities either by redistributing schemes or by larger infrastructures such as the General Infirmary in Bath, which entailed further regulations to control the comings and goings of the poorer sort of invalids.6

- 4. Annick Cossic, ‘The Female Invalid and Spa Therapy in Some Well-Known 18th-Century Medical and Literary Texts: From John Floyer’s The Ancient Psychrolousia Revived (1702) to Fanny Burney’s Evelina (1778)”, in Annick Cossic and Patrick Galliou (eds). Spas in Britain and in France in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2006).

- 5. On the authenticity of women’s sickness and spa treatment see Rose Alexandra McCormack, ‘’An Assembly of Disorders’: Exploring Illness as a Motive for Female Spa-Visiting at Bath and Tunbridge Wells throughout the Long Eighteenth Century’, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 40 (no. 4, 2017), pp. 555–69.

- 6. See Anne Borsay, Medicine and Charity in Georgian Bath: A Social History of the General Infirmary, c. 1739-1830 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999).

Entertainment for the healthier company

As wealthier patients came to visit the spa towns accompanied by healthy families and friends, on the one hand, and were encouraged to exercise and be diverted from the burden of their sickness, on the other, the organisation of leisure became central to the development of spas, and offered further opportunity for sociable interactions. Beyond the pump-room, the walks, gardens and promenades were essential meeting places for exercise and conversation, sartorial display and social observation during the day. Outdoor games such as bowls and pall-mall were a common occupation. Benches, crutches, and wheelchairs such as ‘Merlin Chairs’ facilitated access to the walks for people with disabilities. The famous ‘pantiles’, Tunbridge Wells’ early shopping alley paved in 1700, blended in early consumer culture with the social ritual of the promenade. Longer walks in the surrounding landscape were sometimes designed to enable access to a well, such as Tuewhet wells in Harrogate or the sulphurous well in Moffat (Scotland), in a proto-touristic consumption of the environment, an early form of the ‘commodification of nature’.7 At night, social gatherings depended on the size of the spa and were a sign of one’s social status. Lower middle classes met at inns and taverns. Various clubs, lodges and religious societies mushroomed out of the nearby market towns, while the gentry and upper classes gathered for conventional balls or game nights at the assembly rooms. Gaming and gambling were intrinsically mixed activities in terms of social classes and assembly rooms had spaces dedicated to the occupation – restricted to gaming only after the 1739 and 1745 laws banning professionally-handled gambling. Theatres also thrived on the taste for display, performance and music pervading the whole town, from the early morning music kiosk to the late outdoor spectacles. In some smaller spas, the theatre became more famous than the spa itself, as was the case for Sadler’s Wells Theatre in Islington.

- 7. See K. Glover, ‘Polite Society and the Rural Resort: The Meanings of Moffat Spa in the Eighteenth Century’, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies (34, no. 1, 2011), pp. 65–80 and Barbara M. Benedict, ‘Consumptive Communities: Commodifying Nature in Spa Society’, The Eighteenth Century (36, no. 3, 1995), pp. 203–19.

The Bath assembly rooms, renovated by John Wood the younger in 1771, certainly represent the epitome of late Georgian elite sociability around card-playing games such as quadrille, dancing and tea, with a specific room dedicated to each particular activity. Other assembly rooms such as the Long-Room at Hampstead were under the supervision of masters of ceremonies. Even though their status was loosely defined, masters of ceremonies were crucial to the social life of larger spa towns. They recorded the well-to-do visitors, announced and introduced them to the rest of the society present in the spa town. They entertained guests with their wit and conversational skills, and sometimes oversaw the gaming tables to prevent players from being snared at by sharpers.8 Sometimes they were self-appointed as was the case for Beau Nash who exported his celebrated social skills from Bath to Tunbridge Wells after the death of Bell Causey in 1735. Sometimes there was an arrangement with the corporation in charge of the management of the spa, as was the case in Scarborough where Richard ‘Dickie’ Dickinson was deemed ‘Governor’ of Scarborough in contemporary satirical literature and rented a building adjacent to the spa to assist bathers. Masters of ceremonies actively contributed to the spa’s outreach through their reputation and even by their own writings, such as Simeon Moreau’s 1783 guidebook, A Tour to Cheltenham Spa.

Although the architecture of pump-rooms and assembly rooms is often the focus of spa historians, the development of spa towns hinged on a more private form of real-estate investment: lodgings. Accommodation was crucial to the experience of visitors, and a common trope of spa literature throughout the century was a ghastly review of local inns and private lodgings. And yet, accommodation and restauration developed in spa towns, together with an array of other services and proto-touristic occupations: guides, ushers, confectionary makers and souvenir shops. In parallel with the sociability of visitors, workers also developed forms of sociable encounters and networks of support: bath women, for example, who accompanied the bathers and sold sweets and lozenges in the bath, were organised as a corporation. The role of household employees, who also took the waters, sometimes at different times of the day, or came to fetch water at the well to bring them to their sick employers, is partially recorded in medical treatises, which sometimes directly discuss their cases.

- 8. See Rachael May Johnson, ‘Spas and Seaside Resorts in Kent, 1660-1820’, Ph.D., University of Leeds, 2013 and John Eglin, The Imaginary Autocrat: Beau Nash and the Invention of Bath (London: Profile, 2005).

Real bonds, imaginary spaces

Seen through the lens of gender history, spa towns are distinctive for their highly gendered spaces. They enabled women to interact more easily, perhaps, than they usually did. First of all, they could come on their own, unaccompanied by their husband, to cure specifically female ailments in particular. Women advised each other on water courses and found consolation in each other’s company.9 Because of the daily invitation to exercise and the omnipresence of sickness, their dress could be less contained. The ‘riding habit’, practical clothes for riding with jackets inspired from the shape of men’s jackets, only shorter, grew more and more popular. Women also gathered around specific activities such as confectionary making, which Amanda Herbert argues traced ambiguous interactions between female sociability and the sugar trade.10 Furthermore, within the looser-defined conventions of gendered sociability in spa towns, women could sometimes use their networks to push political agendas, including on a mission for their political husbands, as Elaine Chalus has argued for Lady Rockingham.11 Once the actual visit was over, spas remained a mental space that women could visit and revolve around in their correspondence to continue ‘a conversation of their own’, offering possibilities of fruitful collaborations and helping to cultivate intimate friendships, as Hurley explains about the bluestockings.12

All these gendered interactions are known to us through literature, especially the novels of Jane Austen and Frances Burney (Evelina), in which young women accompany older men or women to a spa town (usually Bath or Bristol Hotwells). These novels insist on the sociability of larger spa towns as a marriage market. In spa comedies, a subgenre of the comedy of manners set in a spa town used by Sheridan and Colman, the marriage market is a pretence for facilitating all forms of fortune-hunting or adultery. Beyond novels and comedies, resort miscellanies such as Tunbrigialia or The Scarborough Miscellany for the year 1734 were published for the season and offered many shorts forms mirroring and satirising the micro-societies of spa towns. By assembling short literary pieces written at the same time, the printers and editors of miscellanies celebrated taste and shaped the local culture, acting both as agents of control through satire and poems a clef, and reflecting on the porosity between the popular and elite cultures. All these literary productions had sickness and treatment in the background, some celebrating the minerals in the bathing waters of a nymph, others satirizing the purging effects of the waters, a shared condition for all who tried them, whatever their status, others still, like Smollett’s Humphry Clinker, following the peregrination of a gouty man in search of a better health (1777). Perhaps the most emblematic publications of spa towns were the local guidebooks, which provided medical information and the daily health-related and social schedule, as well as local anecdotes, architectural comments and rules of conduct. The form became an object of playful rewritings throughout the century, starting with Christopher Anstey’s New Bath Guide (1766), a satirical poem narrating the adventures of the B__n__r__d family at Bath, to which William Fordyce Mavor wrote a sequel in 1781, The Cheltenham Guide; or, Memoirs of the B-n-r-d Family Continued.

Towards the end of the century, many seaside resorts developed and competed with the spas for treatments of hydrotherapy : Margate and Ramsgate rivalled with Weymouth and Scarborough. And yet, the uses of sea water had already started earlier in the century, especially in towns like Scarborough, which offered both mineral waters and sea-bathing.

- 9. See Alain Kerhervé, ‘Writing letters from Georgian spas: the impres- sion of a few English ladies’, in Annick Cossic and Patrick Galliou (eds), Spas in Britain and in France (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2006). Amanda Herbert, ‘Gender and the Spa: Space, Sociability and Self at British Health Spas, 1640–1714’, Journal of Social History (43, no. 2, 2009), pp. 361–83.

- 10. Amanda Herbert, ‘Gender and the Spa: Space, Sociability and Self at British Health Spas, 1640–1714’, Journal of Social History (43, no. 2, 2009), pp. 361–83.

- 11. Elaine Chalus, ‘Elite Women, Social Politics, and the Political World of Late Eighteenth-Century England’, The Historical Journal (43, no. 3, September 2000).

- 12. A. E. Hurley, ‘A Conversation of Their Own: Watering-Place Correspondence Among the Bluestockings’, Eighteenth-Century Studies (40, no. 1, 2006), pp. 1–21.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Borsay, Anne, ‘Visitors and Residents: The Dynamics of Charity in Eighteenth-Century Bath’, Journal of Tourism History (vol. 4, n° 2, 2012), p. 171–80.

Borsay, Peter, ‘Town or Country? British Spas and the Urban–Rural Interface’, Journal of Tourism History (vol. 4, n° 2, 2012), p. 155–69.

Chiari, Sophie and Samuel Cuisinier-Delorme (eds.), Spa Culture and Literature in England, 1500-1800. Early Modern Literature in History (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021).

Cottom, Daniel, ‘In the Bowels of the Novel: The Exchange of Fluids in the Beau Monde’, NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction (vol. 32, n° 2, 1999), p. 157–86.

Hembry, Phyllis M., The English Spa, 1560-1815: A Social History (London: Athlone Press, 1990).

Harley, D., ‘A Sword in a Madman’s Hand: Professional Opposition to Popular Consumption in the Waters Literature of Southern England and the Midlands, 1570-1870’, Medical History. Supplement (n° 10, 1990), p. 48–55.

O’Connell, Anita, ‘Fashionable Discourse of Disease at the Watering-Places of Literature, 1770-1820’, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies (vol. 40, n° 4, 2017), p. 571–86.

Walton, John K. (ed.), Mineral Springs Resorts in Global Perspective: Spa Histories (London: Routledge, 2014).

Walsham, Alexandra, ‘Reforming The Waters: Holy Wells and Healing Springs in Protestant England’, Studies in Church History Subsidia (vol. 12, 1999), p. 227–55.