Résumé

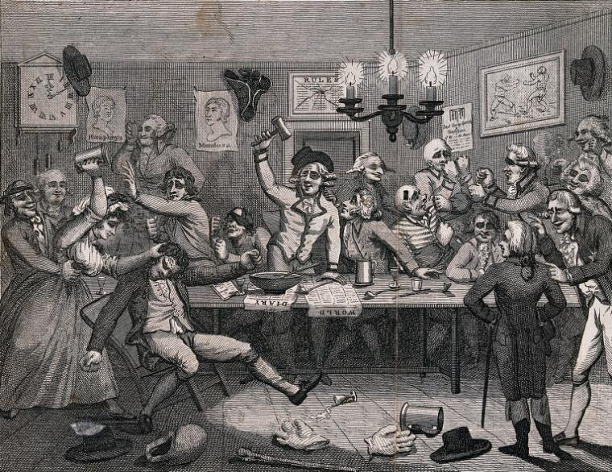

Sporting clubs appeared in the eighteenth century as sports were beginning to organise. They emerged from the more informal gatherings in social places of individuals brought together by their passion for a particular sport – and sometimes by the gambling which this sport made possible. Coffee houses and inns were popular places in the eighteenth century, and some sporting clubs started their lives in such establishments as The Star and Garter Inn. Although sporting clubs are usually associated with the organisation of sports, they were primarily social clubs. Because they were some of the most popular sports in the eighteenth century, this entry is concerned chiefly with the examples of cricket and horse-racing.

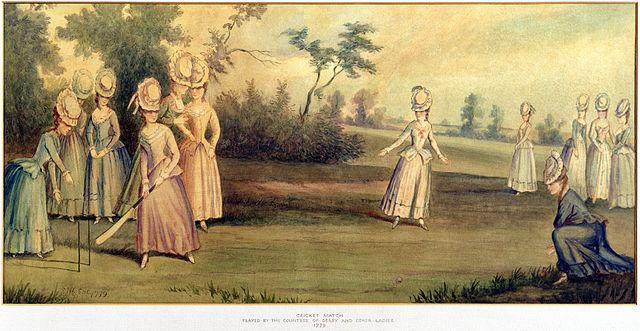

Cricket

While the game of cricket had become popular in the first half of the eighteenth century, the loss of the great patrons of the game (including Frederick, Prince of Wales) meant that the game had to reinvent itself, or at least its organisation had to evolve, if it was going to survive (there was competition from such games as golf). In the late 1760s, what is probably the first cricket club was founded at Hambledon (Hampshire) by former pupils of Westminster School. The Hambledon Club was backed by wealthy patrons. The club’s importance only lasted until the 1790s, because the Marylebone Cricket Club took its place. The Hambledon players are remembered thanks to an important book, The Cricketers of My Time (1832), written by the Shakespeare scholar, Charles Cowden Clarke, and the player John Nyren, who had known most of the players personally. The Hambledon Club

collected together the greatest players of the time, it sent teams (that is, teams got up by members) to other centres, where they were an immediate focus of attraction to people for miles around […], and the playing ability of the teams, as well as its own organization made it a real director of the game, and it was under Hambledon that the transformation was taken so far, though it was probably not started by it.1

The Marylebone Cricket Club, unlike Hambledon, played under its own name. It was originally situated west of the Regent’s Park. Its situation meant that it could attract the nobility and gentry from St James’s, so that its importance was both sporting and social. It then moved to grounds given by Thomas Lord (hence the name of ‘Lord’s’). Originally called the White Conduit Club (because the players, who gathered at the Star and Garter Inn on Pall Mall, played on the White Conduit Fields in Islington), it moved to Lord’s first ground (on the site of the modern Dorset Square) in May 1787, at the instigation of Lord Winchelsea and Charles Lennox, later the 4th Duke of Richmond, and started to be known under the name of Marylebone Cricket Club (it is probable that this was the given name of the club because of its location, but it is not known whether there was an official foundation of the club as all the club records were destroyed by fire in 1825). It was later to move twice and ended up in its present location in 1813.

- 1. Rowland Bowen, Cricket: a History of its Growth and Development throughout the World (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1970), p. 59.

The importance of the club may be linked to its founders and membership being noble and gentlemen cricketers. Above all it became the institution which reviewed the laws of the game; it is now the guardian of these laws. This, of course, as is the case with all sports, did not prevent games being played around the country with different rules. From the second half of the eighteenth century, cricket grew throughout England being recorded, according to Bowen, in thirty-one counties by the end of the century. The first Laws were drawn in 1744, and later revised in 1755 at the Star and Garter, in 1774, and in 1786. Some of these revisions were proposed with a view to controlling gambling. Although there are claims that the Star and Garter was the first cricket club, it is best seen as a meeting place for noblemen and gentlemen, who were looking to organise the rules of the games, rather than as a formal sports club.2

Cricket was played in the colonies, with mentions of games in Aleppo in 1676, and in the West Indies early in the nineteenth century, as well as in Australia and New Zealand. But it was predictably in India that the game flourished. It was being played there early in the eighteenth century. It is in India that the first cricket club outside Britain was established. The Calcutta Cricket Club, now the Calcutta Cricket and Football Club, is the oldest cricket club in the world outside Britain. While there is no exact record of its foundation, it was in existence by 1792, as testified by a mention on 23 February 1792 in the Madras Courier of cricket being played by the Club against ‘the Gentlemen of Barrackpore and Dum-Dum.’ While there are references to games of cricket in India from the 1720s, there is no record of any club as such before the CCC. Until 1825 there was no fixed venue, and cricket matches were played on part of the Esplanade, a favourite place in Calcutta for promenade and leisure, between Fort William and Government House. In 1825, the Calcutta Cricket Club managed to obtain the use of a plot of land on the Maidan. In 1841 the Club was allowed to enclose the ground by putting a fence around it. It had to move in 1864.

- 2. The Star and Garter is also famous for the duel between Lord Byron (grand-uncle of the poet) and Mr. Chaworth, which was fought in a room of the Star and Garter, in January 1765.

Horse-racing

While horse-racing had been in existence for a long time, it really started to develop in England in the seventeenth century. It became an organised sport during the reign of James I. The king paid frequent visits to the village of Newmarket because he enjoyed hunting and hawking ; his court, in particular its Scottish members, initiated races in Newmarket. Later, races developed elsewhere in the country as they provided good testing events for the breed of horses. Charles I continued to patronise Newmarket where important races were established. Having been largely banned during the Commonwealth, racing resumed during the Restoration. In 1665, Charles II instituted the Town Plate, which is still competed for today. The King rode the winner in 1671. The original rules for the event are said to be the first written and published regulations for horse racing (although there is some debate about the nature of the Articles). There were no judges in those days, but any argument had to be referred to the noblemen and gentlemen present, including, on occasion, to the king. William III upheld the royal tradition at Newmarket, which he visited regularly (although, unlike Charles, he was not a horseman). Queen Anne visited Newmarket frequently, and founded Royal Ascot in 1711, on the edge of Windsor Great Park. Racing spread in England in the first half of the eighteenth century and races were held everywhere, thus calling for rules and arbitration, especially given that large sums of money could be at stake.

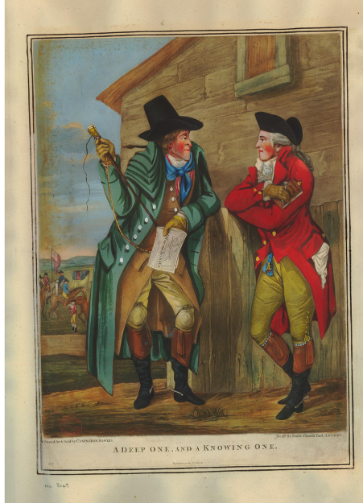

This is the context in which The Jockey Club came into existence. It is mentioned in print in 1752 but some historians (Huggins, Nash, Nichol) have shown that it was already in existence in the 1720s and perhaps earlier. Received opinion was for a long time that the club was formed some time in 1751 because of a mention in print of a meeting of the Club in the Autumn of 1751 (General Advertiser, November 19, 1751). But mentions of The Jockey Club meetings as early as 1729 have been found in newspapers,3 proving that it was already in existence by then. Richard Nash suggests that 1717, the year George I came to a meeting at Newmarket (recorded in a painting by John Wootton), is a likely date for the foundation of the club: ‘a variety of activities and events in the years immediately following suggest that whatever social or sporting organization existed before the royal visit took on a more permanent and lasting form in its immediate aftermath.’4 During this period, The Jockey Club’s activity can be seen through the number of stakes races: one a year until 1728 (known as the Noblemen’s and Gentlemen’s Contribution Purse or the October Stakes), more than four a year between 1729 and 1739, and only twelve in total from 1740 to 1750 (this was in part due to an Act, passed in 1740, imposing that a race should have a prize of at least £50 – this had the immediate effect of reducing the number of races around the country, as well as at Newmarket).

- 3. ‘The Jockey Club, consisting of several Noblemen and Gentlemen, are to meet one Day next Week at Harkwood, the Duke of Bolton’s seat in Hampshire, to consider of Methods for the better keeping of their respective Strings of Horses at New Market’, Daily Post, 2 August 1729.

- 4. Richard Nash, in David Oldrey, Timothy Cox and Richard Nash, The Heath & the Horse: a History of Racing and Art on Newmarket Heath. (London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2016), p. 275. Nash further speculates that the noblemen dining with the King on his arrival in Newmarket (the Dukes of Devonshire, Kent, Montague, Rutland, Roxburghe, and Portland; the Earls of Sunderland and Halifax, the Lord Viscount Lonsdale, and the Lord Harvey) constitute the core of the early Jockey Club.

The Duke of Bolton seems to have been one of the most active members of the club - he was a racehorse owner - and raced his horses at Newmarket. The Earls of Godolphin, of Halifax, Sir William Morgan and Mr Thomas Panton also raced their horses there, on a regular basis, which suggests, equally, membership of the club.5 The membership was distinctly leaning towards the Whigs. This did not prevent certain tradesmen families from taking part in the proceedings of the Club: John Deards, toyman and silversmith, Roger Williams, coffeeman and vintner, and John Cheny, coffeeman. Williams acquired a high profile as a consequence of Edward Coke having bequeathed him his breeding stock. While members of the club originally met at the Star and Garter Inn, it is not inconceivable that Williams’s coffee house in St James’s was The Jockey Club’s first home, and he was certainly involved in commercial transactions of bloodstock.

- 5. The Dukes of Devonshire, Somerset, Bridgewater and Rutland; the Earls of Derby, Bristol and Essex; Lords Lonsdale, Gower and Weymouth; Sir Michael Newton, Sir Richard Groveno, and Edward Coke, Esq. are further likely members of the Jockey Club, according to Nash.

In 1752, the club acquired land at Newmarket, on which was erected a building known as ‘the Coffee Room’ (which no longer exists). The Jockey Club was founded as a social club that brought together landowning noblemen with an interest in racing. As Huggins describes it, ‘the Jockey Club had sufficient wealth, land, political power, social prominence and elite position to impose its own dominant self-image on society at large.’6 When it was relaunched around 1750, having become moribund for a while, its members included the Duke of Hamilton, the Earl of March, Lord Abergaveny, Lord Orford, Mr Vernon and the Earl of Eglington, who rode their own horses. Received opinion was for a long time that racing was organised by the Jockey Club. Its rules for Newmarket were noted but not always followed in other parts of the country. In fact its rules only applied to Newmarket but its cultural significance meant that the rules were sometimes copied in other venues. Newmarket dominated the racing scene because there was more racing there than at any other course in the country.7 From 1770 the Rules and Orders of The Jockey Club were published in the racing calendars. Other exclusive racing clubs were born around the country, such as The Gimcrack Club at York (c.1766), The Bibury Club at Bibury, in Gloucestershire (c.1775), The Maddington Club (c. 1800), The Kingscote Club (1802), The Bagshot Club.

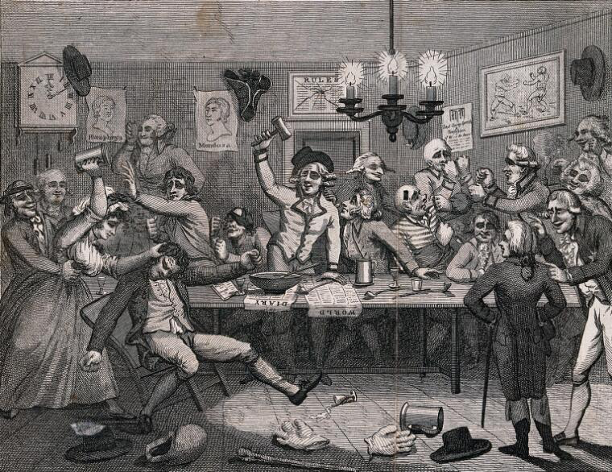

Perhaps because it was an exclusive gathering of noblemen and gentlemen, The Jockey Club attracted satirical allusions and comments in such publications as The New Foundling Hospital for Wit.8 Many Members of Parliament and politicians were spending their time gambling at the races rather than attending to the matters of state. At the end of the century, The Jockey Club, or A Sketch of the Manners of the Age (1792) by Charles Piggott offers a similar picture. It is a vitriolic attack on the aristocracy, with the mention of The Jockey Club serving to attract attention to their debauchery, through gambling in particular. Piggott’s pamphlet is consonant with his support for the French Revolution. He pursued such attacks, against women of the aristocracy, in The Female Jockey Club, or A Sketch of the Manners of the Age (1794).

In the colonies, the Maryland Jockey Club was founded in 1743 in Annapolis, and is possibly the oldest sporting club in North America. It organised racing during the spring and autumn seasons, throughout the eighteenth century, with an interruption during the War of Independence, resuming in 1782. It was attended frequently by George Washington. The Jockey Club of Philadelphia was founded in 1766. The first race course in India was established in 1777 at Madras, where the Madras Race Club was established in 1837. The Bengal Jockey Club came into existence in Calcutta in 1803.

- 8. A satirical miscellany published between 1768 and 1773, which resurrected the older Foundling Hospital for Wit, published between 1743 and 1749.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Bowen, Rowland, Cricket: a History of its Growth and Development throughout the World (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1970).

Ganguly, Narendranath, The Calcutta Cricket Club: Its Origin and Development (Calcutta, 1936).

Gupta, Sujoy, Seventeen Ninety Two. A History of the Calcutta Cricket & Football Club (Calcutta: Calcutta Cricket and Football Club, 2002).

Huggins, Mike, Horse racing and British Society in the Long Eighteenth Century (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2018).

Lewis, Tony, Double century: the Story of MCC and Cricket (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1987).

Mallinckrodt, Rebekka von (ed.), A Cultural History of Sport in the Age of Enlightenment (1650‒1800), vol. 4 of Bloomsbury Cultural History of Sport (London: Bloomsbury, 2021).

Mortimer, Roger, The Jockey Club (London: Cassell, 1958).

Nichol, Donald W., 'Jockeying for Position: Horse Culture in Poetry, Prose, & The New Foundling Hospital for Wit', in Sharon Harrow (ed.), British Sporting Literature & Culture in the Long Eighteenth Century (Burlington: Ashgate, 2015), p. 125-150.

Oldrey, David, Cox, Timothy and Nash, Richard, The Heath & the Horse: a History of Racing and Art on Newmarket Heath. (London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 2016).

In the DIGIT.EN.S Anthology

The Sporting Magazine (1793)