Abstract

Coffeehouses were key centres of sociability in eighteenth-century Britain. They played an important role both as real spaces for social interaction and as virtual places in which normative ideals of urban and polite sociability were imagined. Coffeehouses were centres of sociability because they brought people together for the ostensible purpose of drinking coffee, but they also encouraged discussion and often debate over matters of common interest. News gathering, news reading and news sharing were as integral to coffeehouse sociability as coffee drinking. Rather than seeing the coffeehouse as a wholly unique and liberal institution, more recent studies have emphasized the ways in which it emerged out of, and was integrated into, the social structures of early modernity. Rather than replacing older drinking spaces such as the alehouse or the tavern, the rise of the coffeehouse is now best understood as the emergence of a complementary sociable institution.

Keywords

Coffeehouses were key centres of sociability in eighteenth-century Britain. They played an important role both as real spaces for social interaction and as virtual places in which normative ideals of urban and polite sociability were imagined. The first coffeehouses were established in England in the 1650s, possibly in London or perhaps in Oxford. Pasqua Rosee’s coffeehouse in in the parish of St Michael Cornhill, London opened in 1652, and in the same year he published a handbill advertisement entitled The Vertue of the Coffee Drink (c.1652), in which he claimed credit for being the first person to sell coffee publicly in England. By 1656, James Farr, had established the Rainbow Coffeehouse in competition with Rosee and soon thereafter many other coffeehouses began to proliferate. By 1663, there were eighty-two coffeehouses in the City of London and likely many more in the greater metropolitan region. The London Directories of 1734 noted that there were 551 officially licensed coffeehouses in London, although there were surely many more unlicensed coffeehouses as well.1 The first coffeehouse patrons were natural philosophers (virtuosi) and merchants who had encountered coffee drinking in their travels to the Ottoman Empire, but they quickly began to cater to a much broader clientele of urban consumers who had an interest in drinking the new exotic hot beverage. By the Restoration era, coffeehouses served a broad urban clientele. London had vastly more coffeehouses than any other city in the British world, although by the end of the seventeenth century almost all cities in England, Scotland and Ireland had at least one coffeehouse.

- 1. Markman Ellis, The Coffee-House: A Cultural History (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004); Brian Cowan, The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2005), p. 94-95, 154.

Coffeehouses were centres of sociability because they brought people together for the ostensible purpose of drinking coffee, but they also encouraged discussion and often debate over matters of common interest. News gathering, news reading and news sharing were as integral to coffeehouse sociability as coffee drinking. Newspapers were often distributed and read at coffeehouses, and news writers often gathered information in the coffeehouses. In the seventeenth century, this association between coffeehouses and news culture brought the institutions under suspicion and several attempts to either ban or strictly regulate coffeehouses were made during the reigns of Charles II, James VII and II, and William III.2 By the early eighteenth century, however, the coffeehouse had become an established and accepted feature of the British urban social order. The association between coffeehouse sociability and freedom of expression was so well entrenched by the later eighteenth century that John Frost, a radical attorney and founding member of the Society for Constitutional Information, defended himself from prosecution for uttering seditious words at the Percy Coffeehouse by claiming that he had expressed himself freely under the expectation that discourse amongst friends at a coffeehouse constituted private conversation that should be protected from public scrutiny by the state. What had once been understood as a space for public declarations in the later Stuart era had become understood as a place of private refuge by the later Hanoverian era.3

- 2. By the King. A proclamation for the suppression of coffee-houses (London: John Bill, and Christopher Barker, 1675); Cowan, Social Life of Coffee, p. 194-216.

- 3. John Barrell, ‘Coffee-House Politicians’, Journal of British Studies (43:2, April 2004), p. 206-232; Brian Cowan, ‘Publicity and Privacy in the History of the British Coffeehouse’, History Compass (5:4, July 2007), p. 1180-1213.

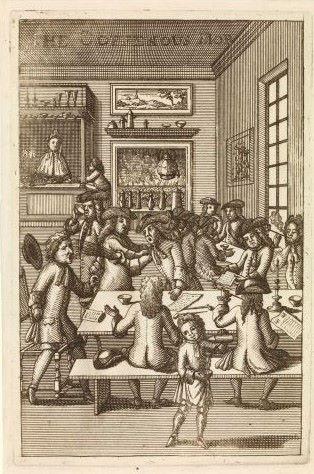

Coffeehouses were idealized by early eighteenth-century writers and theorists of sociability such as Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in their Tatler (1709-1711) and Spectator (1711-1712, 1714) periodicals. In The Spectator, Addison famously declared: ‘I shall be ambitious to have it said of me, that I have brought Philosophy out of Closets and Libraries, Schools and Colleges, to dwell in Clubs and Assemblies, at Tea-tables, and in Coffee houses.’ (The Spectator n° 10, 12 March 1711) Addison’s and Steele’s essays in these papers played an important role in establishing an ideal of polite, urban sociability that they thought should prevail in English coffeehouses even if they tended to lament the lack of politeness that they saw in those places. They promoted an ideal whereby coffeehouse conversation should be informed, witty, and wise.4 While this model of polite coffeehouse sociability remained an ideal, it became an ever more powerful one over the course of the eighteenth century. It is perhaps telling that early eighteenth-century visual representations of coffeehouses tend to present them as chaotic, dangerous and often violent places, whereas later eighteenth-century images of coffeehouses present them as quiet, calm and peaceful spaces for quiet reflection.5

- 4. Brian Cowan, ‘Mr. Spectator and the Coffeehouse Public Sphere’, Eighteenth-Century Studies (37:3, 2004), p. 345–356.

- 5. Compare ‘The Coffeehous Mob’ (c. 1710), frontispiece to Edward Ward, The Fourth Part of Vulgus Britannicus: or the British Hudibras (35.5 x 26.2 cm), British Museum [BM] Department of Prints and Drawings, Catalogue of English Cartoons and Satirical Prints, 1320–1832 [BM Sat.] 1539; with C. Lamb after G. M. Woodward, ‘A Sudden Thought’ (London: S. W. Fores, 1 Jan. 1804), etching and stipple, (25 × 35.5 cm), BM Sat. 10325.1, Lewis Walpole Library, [LWL] 804.1.1.7.

Coffeehouses hosted a variety of different activities besides coffee drinking and news mongering. They served as post offices for the collection and reading of correspondence. In the 1680s, the Penny Post used coffeehouses as both pick-up and delivery centres. By the 1780s, the Gloucester Coffeehouse in Picadilly accepted and received correspondence from the West Country (Cowan, Social Life of Coffee, 175-77). They were sales centres in which goods and services could be bought and sold. Some of the earliest auctions of books, art works, and real estate were held in coffeehouses. Many professionals used coffeehouses as a surrogate office for meeting with clients and for conducting business. The insurance industry developed in coffeehouses such as Lloyd’s, a coffeehouse which became the forerunner of the global insurance corporation Lloyd’s of London (Cowan, Social Life of Coffee, 132-45, 165). By the mid-eighteenth century, some coffeehouses had developed substantial reading libraries. Booksellers were often affiliated with coffeehouses as convenient places to locate customers and distribute their works.6

- 6. Markman Ellis, ‘Coffee-House Libraries in Mid-18th-Century London’, The Library: Transactions of the Bibliographical Society (10.1, 2009), p. 3–40.

Coffeehouse sociability was predominantly masculine. Since coffeehouses were often little more than a room within a larger household, it was not uncommon for men and women to be found together in some coffeehouses. Although women participated in coffeehouse society, they did so primarily as proprietors (coffee-women) or as visitors to coffeehouses in order to ply their trade. This was particularly true for those coffeehouses that served as spaces for sex workers.7 Nevertheless, the Addisonian ideal of polite coffeehouse sociability was a predominantly masculine one, and it had little place for heterosocial interactions. Although The Spectator was designed to read by both men and women, it reserved the coffeehouse for male sociability and the tea table for women. This sense of the coffeehouse as a masculine space would only be reinforced later in the eighteenth century by the Johnsonian ideal of manly conversation promoted by James Boswell in his Life of Johnson (1791).8

The gradual assimilation of the coffeehouse into the habitual patterns of urban sociability over the course of the eighteenth century allowed it to be taken for granted by the Hanoverian era. The success of the Addisonian coffeehouse ideal made the coffeehouse a less controversial place and as a consequence it figures less prominently in the social discourse of the later eighteenth century. The gradual diminishment of debates about coffeehouse sociability has led some commentators to believe that coffeehouses were ultimately replaced by clubs as the eighteenth century wore on. In fact, the history of clubs and coffeehouses remained intertwined throughout the period. From the first meetings of the Rota Club in the 1650s to the meetings of Johnson’s famous Club in the age of George III, clubs and coffeehouses played a complementary role in satisfying the need for sociable spaces.9

- 9. Peter Clark, British Clubs and Societies 1580-1800: The Origins of an Associational World, (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2000); Valerie Capdeville, L’âge d’Or des Clubs Londoniens (1730‑1784), (Paris, Honoré Champion, 2008).

Due to its prominence as a setting for some of the best-known works of eighteenth-century literary production, from the Tatler and The Spectator to The Life of Johnson, the coffeehouse has played an important role in the way in which sociability has been understood by historians and critics of the era. Thomas Babington Macaulay used the coffeehouse as key example of how English society worked in the 1680s in his influential History of England from the Accession of James the Second (1848). Macaulay’s description of the later Stuart coffeehouse was memorable. The coffeehouse, he declared:

‘[...] might indeed [be] called a most important political institution. No Parliament had sat for years. The municipal council of the City had ceased to speak the sense of the citizens. Public meetings, harangues, resolutions, and the rest of the modern machinery of agitation had not yet come into fashion. Nothing resembling the modern newspaper existed. In such circumstances, the coffee houses were the chief organs through which the public opinion of the metropolis vented itself … Foreigners remarked that the coffee house was that which especially distinguished London from all other cities; that the coffee house was the Londoner's home, and that those who wished to find a gentleman commonly asked, not whether he lived in Fleet Street or Chancery Lane, but whether he frequented the Grecian or the Rainbow. Nobody was excluded from these places who laid down his penny at the bar. Yet every rank and profession, and every shade of religious and political opinion, had its own headquarters‘.10

Macaulay presented a Whig history of the coffeehouse in which this new social institution served as a venue for the forging of public opinion and which was open to all comers. As such, it appeared to play a key role in the development of what would ultimately come to be known as liberal democracy. This view would be reinforced over a century later in Jürgen Habermas’s famous thesis on The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962; Eng. Trans. 1989). Here, Habermas presented the coffeehouse as an exemplar of the newly emergent bourgeois public sphere in which rational discourse and unhindered debate was encouraged. The Habermasian model has remained influential, but it has been subjected to revisionist criticism in the twenty-first century. Rather than seeing the coffeehouse as a wholly unique and liberal institution, more recent studies have emphasized the ways in which it emerged out of, and was integrated into, the social structures of early modernity. Rather than replacing older drinking spaces such as the alehouse or the tavern, the rise of the coffeehouse is now best understood as the emergence of a complementary sociable institution.

- 10. Thomas Babington Macaulay, History of England from the Accession of James the Second (1848).

Share

Further Reading

Cowan, Brian, ‘Publicity and Privacy in the History of the British Coffeehouse‘, History Compass (vol. 5, n°4, July 2007, p. 1180-1213). Wiley Online Library,http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2007.00440.x/abstract.

_____________, The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2005).

_____________, ‘Mr. Spectator and the Coffeehouse Public Sphere.‘ Eighteenth-Century Studies (vol. 37, n° 3, 2004), p. 345-356.

_____________, ‘What Was Masculine about the Public Sphere? Gender and the Coffeehouse Milieu in Post-Restoration England‘, History Workshop Journal (vol 51, n° 1, 2001), p. 127–157.

Ellis, Markman, The Coffeehouse: A Cultural History, (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004).

_____________, ‘Coffee-House Libraries in Mid-Eighteenth-Century London‘, The Library: Transactions of the Bibliographical Society (vol 10, n° 1, 2009), p. 3-40.

Habermas, Jürgen, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. Thomas Burger (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 1989).

Klein, Lawrence, ‘Coffeehouse Civility, 1660–1714: An Aspect of Post-courtly Culture in England', Huntington Library Quarterly (vol 59, n° 1, 1997), p. 30–51.

Smith, Woodruff D., Consumption and the Making of Respectability, 1600-1800 (New York: Routledge, 2002).

![C. Lamb after G. M. Woodward, ‘A Sudden Thought’, (London: S. W. Fores, 1 Jan. 1804), etching and stipple, (25 × 35.5 cm), BM Sat. 10325.1; Lewis Walpole Library, [LWL] 804.1.1.7](/sites/default/files/styles/notice_full/public/2024-02/COFFEEHOUSES%202.jpg?itok=-aeOCzCz)