Quote

"A strange spirit of fury had broke loose on some of the presbyterians, called the Cargillites, from one Cargill that had been one of the ministers of Glasgow in the former times, and was then very little considered, but now was much followed, to the great reproach of the nation."

Links to the Encyclopedia:

JAMES IN SCOTLAND.

The duke behaved himself upon his going to Scotland in so obliging a manner, that the nobility and gentry, who had been so long trodden on by duke Lauderdale and his party, found a very sensible change so that he gained much on them all. And though he continued still to support that side, yet things were so gently carried, that there was no cause of complaint. It was visibly his interest to make that nation sure to him, and to give them such an essay of his government, as might dissipate all the hard thoughts of him with which the world was possessed and he pursued it for some time with great temper and as great success. He advised the bishops to proceed moderately, and to take no notice of conventicles in houses, and that would put an end to those in the fields. In matters of justice he shewed an impartial temper, and encouraged all propositions relating to trade and so, considering how much that nation was set against his religion, he made a greater progress in gaining upon them than was expected! He was advised to hold a parliament there in summer 82, and to take the character of the king's commissioner upon him.

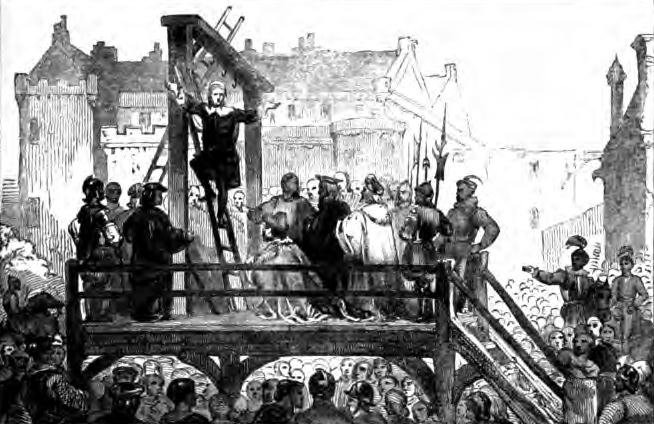

A strange spirit of fury had broke loose on some of the presbyterians, called the Cargillites, from one Cargill that had been one of the ministers of Glasgow in the former times, and was then very little considered, but now was much followed, to the great reproach of the nation. These held that the king had lost the right to the crown by his breaking the covenant, which he had sworn at his coronation so they said he was their king no more, and by a formal Declaration they renounced all allegiance to him, which a party of them affixed to the cross of Dumfries, a town near the west border. They also taught that it was lawful for any to kill him, and that all his party, chiefly those who were episcopal, by adhering to him, had forfeited their lives; so that it was lawful to kill them likewise. The guards fell upon a party of them whom they found in arms, where Cameron, one of their furious teachers, from whom they were also called Cameronians, was killed but Hackston, that was one of the archbishop's murderers, and Cargill, were taken. Hackston, when brought before the council, would not own their authority, nor make any answer to their questions. He was so low by reason of his wounds, that it was thought he would die in the question if tortured so he was in a very summary way condemned to have both his hands cut off, and then to be hanged. All this he suffered with a constancy that amazed all people. He seemed to be all the while as in an enthusiastical rapture, and insensible of what was done to him. When his hands were cut off, he asked, like one unconcerned, if his feet were to be cut off likewise and he had so strong a heart, that notwithstanding all the loss of blood by his wounds, and the cutting off his hands, yet when he was hanged up, and his heart cut out, it continued to palpitate some time after it was on the hangman's knife, as some eye-witnesses assured me. Cargill, and many others of that mad sect, both men and women, suffered with an obstinacy that was so particular ”, that though the duke sent the offer of pardon to them on the scaffold, if they would only say God bless the king, it was refused with great neglect one of them said very calmly, she was sure God would not bless him, and that therefore she would not take God's name in vain the other said more sullenly, that she would not worship that idol, nor acknowledge any other king but Christ and so both were hanged. About fifteen or sixteen died under this delusion, which seemed to be a sort of madness for they never attempted any thing against any person only they seemed glad to suffer for their opinions. The duke stopped that prosecution, and appointed them to be put in a house of correction, and to be kept at hard labour. Great use was made of this by profane people to disparage the suffering of the martyrs for the Christian faith, from the unshaken constancy which these franti people expressed. But this is undeniable that men who die maintaining any opinion, shew that they are firmly persuaded about it. So from this the martyrs of the first age who died for asserting a fact, such as the resurrection of Christ, or the miracles they had seen, shewed that they were well persuaded of the truth of those facts ; and that is all the use that is to be made of this argument.