Résumé

London Bookshops are no longer seen restrictively as retailing and publishing venues where books were made and sold. Whether it be in the City or in the polite West End, they fulfilled a wide range of functions (mail, banking, politics). Their crucial significance in various social circles could be best explained by the connections to other public places such as coffee-houses, taverns, markets and many cultural institutions (clubs, libraries, antiquarian circles). Most printers and booksellers were amphibious businessmen, whose prosperity depended on their ability to liaise with customers from various social backgrounds (urban middle-sort, the national landed elites).

In his Autobiography, Dr. Alexander Carlyle, a founding member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, described his encounter with Andrew Millar, a prominent London bookseller who was visiting Harrogate in 1763. Publisher of Fielding, Johnson and Hume, Millar was considerably wealthy and left an estate at his death valued at £60,000. However, his presence in a fashionable spa town in Yorkshire, popular with the landed gentry, was met with much sarcasm. Carlyle noted that if ‘all the baronets and great squires’ were civil enough to read Millar’s newspaper The General Evening Post, they refused to consider him as their own:

When he appeared in the morning in an old well-worn suit of clothes, they could not help calling him Peter Pamphlet; for the generous patron of Scotch authors, with his city wife and her niece, were sufficiently ridiculous when they came into good company.1

Admittedly, eighteenth-century booksellers were key agents in the strengthening of a public sphere in Britain, but their social status and their retailing activities in the City prevented them from being admitted in ‘good company’. Their shops, scattered between the City and the polite West End, encapsulated their complex position, at the crossroads between different social scenes and backgrounds. In the last decades, the contribution of London printers and booksellers to eighteenth-century spheres of sociability has been mapped out by many book historians and their research has led to a recent scholarship, whose richness and complexity can not be easily summarised. In this entry, three main subjects have been explored, namely, the constant adaptation of the printing business to a changing social world, the inclusive and exclusive potential of bookshops and the extension of the booksellers’ social networks beyond the metropolis.

- 1. Autobiography of the Rev. Dr. Alexander Carlyle, Minister of Inveresk: Containing Memorials of the Men and Events of His Time (London, 1861), p. 434.

In the eighteenth century, the ‘London bookscape’ offered many contrasting views to contemporaries, from the ancient and crowded tenements around St Paul, characterised by ‘frenetic and predominantly male stopping-off places enjoyed by Evelyn or Pepys’2 to the large and polite shops in the West End, which were visited by men and women alike. The spatial turn which has been applied with great success by urban historians such as Peter Borsay, is also well adapted to make sense of the relation between space, bookshops and urban sociability. As James Raven has pointed out, the community of London booksellers and printers managed to adapt themselves to the considerable expansion of the metropolis westwards while preserving a stable centre in the City around St Paul’s Churchyard and Paternoster Row: ‘the ability of booksellers to remain within a particular neighbourhood, irrespective of changing needs for space, proved a valuable feature in the changing city’.3 In the urban landscape, it is worth stressing that sociability relied on various venues which were connected to each other. In a stimulating chapter on the ‘sites of Natural Knowledge’, Adrian Johns reminded us of the complementarity between coffee houses and print shops in Early-Modern Europe: ‘Early coffee-houses had often abutted onto booksellers’ shops, and well into the eighteenth century the economic power of coffeehouse audiences remained strongly influential on the output of their community’.4 In the City, booksellers were running their activities from nearby coffeeshops and taverns, where they would meet to exchange copyrights, to organise public reading and auction sales. If copyright sharing was done secretly among the most influent booksellers, public reading and auctioneering attracted large crowds. From the City, booksellers and printers followed an East-West axis of circulation and prospered on Fleet Street or in Piccadilly by turning their venues into ‘fashionable lounging places’ in the late eighteenth-century.5 As such, they stood in between the traditional civic life of the City and the expanding West End. This uneasy balance between stability and novelty could also be seen in most London social spheres, which relied equally on early modern taverns and coffeehouses and new sources of attractions around parks, clubs and polite societies. In their ubiquitous presence, printers and booksellers managed to fulfil an endless list of tasks, from the expected ones (publishing and selling books) to ‘a diverse range of services, including carriage, warehousing, public notification, and even banking’ (Raven, Bookscape, 103). By doing so, they managed to meet the often conflicting demands of a considerable range of customers from clergymen, politicians, merchants to the visiting gentlemen and gentlewomen. Their omnipresence also came from the fact that they themselves were engaged in many activities, from journalism (Abel Roper), novel writing (Samuel Richardson), politics (William Strahan) or antiquarianism (Richard Nutt).

- 2. James Raven, Bookscape: Geographies of printing and publishing in London before 1800 (London, 2014), p. 144.

- 3. James Raven, The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade, 1450-1850 (Yale, 2007), p. 155; James Raven, Publishing Business in Eighteenth-Century England (Woodbridge, 2014).

- 4. Adrian Johns, ‘Coffeehouses and Print Shops’ in by L. Daston and K. Park (eds), The Cambridge History of Science, III: Early Modern Science (Cambridge, 2006), p. 333.

- 5. Ian Maxted, The London Book Trades, 1775-1800 (Folkestone, 1977), p. xii.

A second line of thought deals with a fundamental tension within the urban sociability which has been well explored by Peter Borsay, namely that ‘the promotion of sociability sits rather uneasily alongside that other great preoccupation of urban culture, the pursuit of status. Whereas one sought to unify society, the other encouraged fragmentation. The two motives cannot be easily harmonized; nor should they be’.6 Similarly, in several books, historians have contended that the commercialisation of books and prints did not necessarily lead to a more open society. Prices of drinks and prints were not cheap and many bookshops and coffeehouses were restricted to wealthy consumers. As for most coffeehouses and circulating libraries, the idea that bookshops provided a levelling environment for all Londoners is open to question. Throughout most of the eighteenth century, books and printed newsletters remained unaffordable for most of the London inhabitants. Organised in tightly knit groups, many London booksellers were actually able to preserve considerable margins on their largely overpriced books. The legal case of Donaldson v Becket, brought by a Scottish bookseller in 1774 against his London competitors, might have led to the growth of many cheaper and abridged editions but on the whole, books remained expensive commodities right until 1810. Furthermore, many historians have stressed the need to better connect bookselling to segregated cultural practices such as reading, browsing and even talking.7 Practices of reading and conversation were deeply intertwined. Prints both enable and transform different levels of sociability. Research has been carried out on the interior of bookshops, on their furniture and layout. There was an underlying tension between the need to enjoy confined and private reading or browsing space and the appeal of vast and inclusive shops.

- 6. Peter Borsay, The Urban Renaissance: Culture and Society in the Provincial Town 1660-1770 (Oxford, 1989), p. 278.

- 7. See William St Clair, The Reading Nation in the Romantic period (Cambridge, 2004); James Raven, Helen Small, Naomi Tadmor, The Practice and Representation of Reading in England (Cambridge, 2007).

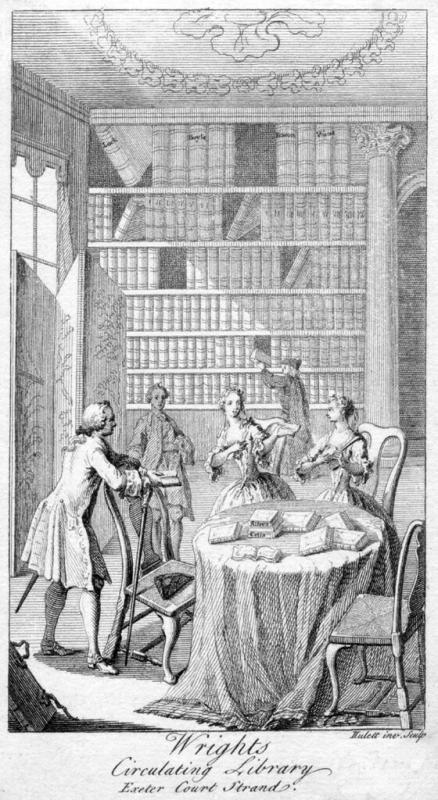

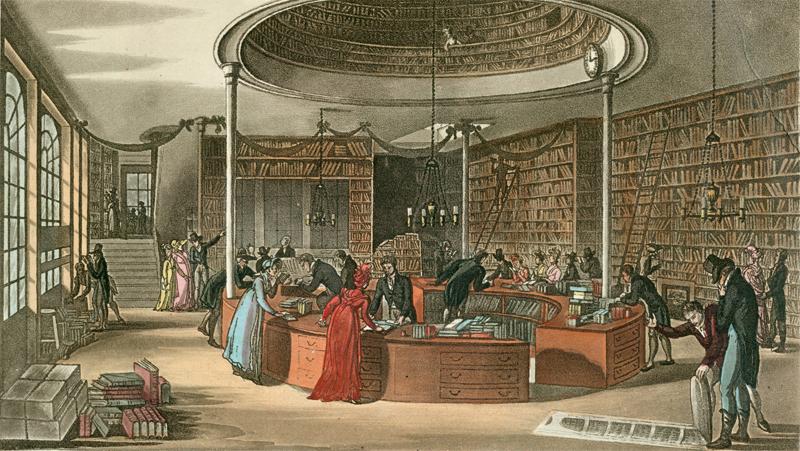

Many books were ordered by mail or fetched by servants but increasingly, customers were invited to come in person. Thomas Becket described his shop not ‘as a repository of rational amusement but as a museum from when can be withdrawn materials capable of forming the minds of readers to solid virtues, true politeness, noblest actions and purest benevolence’ (Raven, The Business of Books, 113-114). Increasingly, bookshops were fashioned by their owner in order to provide an attractive environment for their customers, who therefore visited their venues not only to buy books but also to socialise. Historians can rely on the many engraved views of bookshops in advertisement such as Wright’s Circulating Library Catalogue (c. 1755) or in larger volumes such as Rudoph Ackermann, Repository of Arts (1809-29). These visual sources enable us to see various idealised customers, their use of space and the interpersonal dynamics which took place. Wright’s shop displayed the expensing folios at the top of the shelves while quartos were lying on the table for anyone to handle.8 It has been argued that the shops of Longman and Rivington ‘offered the promise of an intimate space behind the street façade and the bow windows’ while others like the one owned by James Lackington provided a more ‘public space’ (Raven, Bookscape, 141). His vast circulating libraries thrived on a strong associational life which enabled social mixing.

- 8. Edward H. Jacobs, ‘This shelving protocol elevated the less numerous and generically more restricted folios to positions that required the use of tools such as ladders and the "pastoral" intervention of a shop keeper, distancing folios from casual modes of selection based on browsing and, in turn, giving them a certain "elite" status’. ‘Buying into Classes: The Practice of Book Selection in Eighteenth-Century Britain’, Eighteenth-Century Studies (vol. 33, n° 1, 1999), p. 57.

Finally, the contribution of London booksellers to various forms of sociability could be appreciated by considering their extended networks established through Britain, Europe and across the Atlantic. Apart from his bookshop in London (Temple of Muse), James Lackington owned outlets in Oxford, Cambridge, Bath, Coventry, Bristol and Newcastle (Raven, The Business of Books, 290). Many affluent London booksellers were not cut off from the wider sphere of sociability. William Innys lived in Bristol until his apprenticeship in London with Benjamin Watford started in 1702. John Almon remained strongly attached to Liverpool, where he was born. There were numerous booksellers of Scottish descent (Millar, Strahan, Donaldson) who kept their connections with Glasgow and Edinburgh. As far as the American towns were concerned, various studies have underlined the similarities between the provincial and Atlantic book selling networks. In terms of cost and time, they were roughly equivalent.9 Their shops welcomed visitors and travellers from all over Britain and were instrumental in maintaining the culture identities of many distinct communities. An extensive database of John Nichols’ letters demonstrated his central position in a vast network of correspondents extending far beyond the City.10 As a baker’s son, an apprentice in the Stationers’ company and the owner of a prosperous bookshop in fleet street, he had developed strong connections within the Livery companies and the civic institutions. Like many other booksellers, he was intimately linked to scholarly societies such as the Royal Society, the Society of Antiquaries of London.11 As a publisher of county histories and of the Gentleman’s Magazine, he had among his correspondents, many country gentlemen and gentlewomen who contributed to the editing process and to his editorial policy. His networks went far beyond the UK to reach the American colonies and the continent. Similarly, his volumes of biographical memoirs (Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century [1812-1815]), which abound with personal encounters in his shop, provide a striking view of the vast sociability of a single London bookseller.12

- 9. Mark Towsey, Kyle B. Roberts (eds.), Before the Public Library: Reading, Community, and Identity in the Atlantic World, 1650–1850 (Leiden, 2018).

- 10. See Julian Pooley and his Nichols Database at the Surrey History Centre in Woking http://www2.le.ac.uk/centres/elh/research/project/nichols/the-nichols-archive-project; Edward L. Hart (ed.) Minor Lives. A Collection of Biographies by John Nichols (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1971).

- 11. Julian Pooley, ‘A Laborious and Truly Useful Gentleman’: Mapping the Networks of John Nichols (1745-1826), Printer, Antiquary and Biographer’, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies (vol. 38 n°4,2015), p. 497-509.

- 12. John Nichols, Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century, 9 vols. (London, 1812-1815).

Partager

Références complémentaires

Bell, Bill, Bennet, Philip and Bevan, Jonquil (eds.), Across Boundaries: The Book in Culture and Commerce (New Castle: Oak Knoll Press; Winchester: St. Paul's Bibliographies, 2000).

Bermingham, Ann and Brewer, John (eds.) The Consumption of Culture 1600-1800: Image, Object, Text (London and New York: Routledge, 1995).

Daybell, James and Hinds, Peter (eds.), Material Readings of Early Modern Culture: Texts and Social Practices, 1580-1730 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

Elliott, J. E., ‘The Cost of Reading in Eighteenth-Century Britain: Auction Sale Catalogues and the Cheap Literature Hypothesis’ ELH (vol. 77, n° 2, 2010), p. 353-384.

Raven, James, Small, Helen, and Tadmore, Naomi (eds.), The Practice and Representation of Reading in England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Isaac, Peter and McKay, Barry (eds.), The Human Face of the Book Trade: Print Culture and Its Creators (New Castle: Oak Knoll Books; Winchester, U.K.: St. Paul's Bibliographies, 1999).

Jackson, Ian, ‘Approaches to the History of Readers and Reading in Eighteenth-Century Britain’ Historical Journal (vol. 47, n° 4, 2004), p. 1041-1054.

In the DIGIT.EN.S Anthology

Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century (1812).