Résumé

Georgian menageries are to be seen as the predecessors to the more formal zoological societies of the Victorian era. As the British Empire expanded, private and public menageries were populated by exotic animals seen as objects of fascination and wonder and whose aim was to entertain visitors and guests as well as to satisfy the curiosity for the animal world. In such places of sociability, exotic animals became commodities to be entertained by and to consume collectively thereby becoming part of London life in the eighteenth century. Privileged gentry, aristocracy, and ordinary people established social relations in menageries in which they also expressed cultural attitudes and concerns.

Royal Menageries: The Queen’s Zebra

Seen as an establishment of luxury and curiosity a menagerie was, in eighteenth-century England, a collection of captive exotic animals kept by aristocratic and royal courts for attesting their power and wealth. Such a place of social interaction fostered the encounter between members of the nobility and ordinary Georgians who visited menageries with a desire to marvel at wild animals imported from Africa, the Americas, Asia and later from Australia. The exhibition of unfamiliar animals resulted into polite and satirical conversations about the trade, the cultural meaning and the social interactions of exotic animals with Londoners during the long eighteenth century. The Duke of Marlborough, Sir Hans Sloane, the Duchess of Portland, the Duke of Cumberland, the Earl of Shelburne, Sir Robert Walpole, the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham, and many others used to collect exotic animals in their private menageries whose functions were not primarily scientific and educational but rather of pleasurable interaction for, sometimes, both humans and animals.

The close bodily engagement with exotic animals is exemplified by Queen Charlotte’s royal menagerie which was first home to pheasants and other exotic birds, but by 1792 also contained some of the first kangaroos to arrive in Britain, including a female zebra who quickly became a celebrity for her ungovernable behaviour and vicious personality. Notably, crowds flocked to see Queen Charlotte’s zebra at Buckingham palace where they had the chance to admire for free the black-and-white striped beast always kicking and biting her keepers. Brought from South Africa as a wedding gift from Sir Thomas Adams for young Queen Charlotte, the female zebra was nicknamed ‘The Queen’s she-ass’ and produced such a degree of excitement that George Stubbs was commissioned to portray the celebrated animal in 1763.

Satirical prints and songs about the zebra were produced as symbolic representations of the royal political rivalry and corruption. The connection between the Queen and her female zebra was so notable that a humorous allegorical song was composed: ‘What prospect so charming! / What can surpass? / The delicate sight of her M------‘s A--?’.1 This rude song surviving in a printed broadsheet is an example of the amusement that the Georgians derived from the zebra jokes and from the many references that could be found in newspapers (London Magazine and Gentleman’s Intelligence; Lloyds Evening Post; Gazette and New Daily Advertiser; Middlesex Journal or Chronicle of Liberty, Jackson’s Oxford Journal and many others). The public opinion was soon outraged at the three-penny admission fee illegally required by the Queen’s Guard who refused to show the zebra without being paid. Numerous indignant letters appeared in London newspapers especially because the Queen was not able to stop such sordid doings. This social place of attraction supposed to amaze and amuse the crowd became unexpectedly a space of criminality and corruption attracting numerous pickpockets. Despite these mass crimes which occurred at the stables of Buckingham Palace or around the zebra’s paddock, the Georgians were still attracted by the Queen’s royal menagerie. Following the sociology of social interaction and group dynamics by Georg Simmel, Queen Charlotte was able to affect the masses by appealing to their feeling of excitation caused by the presence of exotic animals resulting in the ‘avalanche-like growth of the most negligible impulses of love and hate’.2 Georgian crowds exhibited a collective sensitivity, a passion, an eccentricity that was fostered by their physical proximity with exotic animals, ‘an excitation […] [which] is one of the most revealing, purely sociological phenomena that the individual feels himself carried by the ‘mood’ of the mass’ (Simmel 35).

The Queen’s zebra became a socio-cultural phenomenon attracting the attention of such eminent philosophers and writers as Voltaire, Rousseau, Walpole, the Rev. William Mason, the poet William Wallbeck and many others. In particular, Voltaire, while describing the English people to Rousseau, mentioned that they love to amuse themselves with ‘oddities of any kind’,3 that is to say with such exotic animals as the king’s elephants and the queen’s zebra. Likewise, Walpole and Mason exchanged witty letters on the zebra whose dead body was put on display at the Blue Boar Inn in York. In a letter dated 2 June 1773, Mason empathises with the zebra’s pitiable fate of being exhibited as a living animal for 10 years and then being exposed as a dead skin in a less salubrious accommodation than the stable at Buckingham. Mason encourages moral reflections on the zebra’s story which, in his view, is endowed with the didactic power of Ovid’s Metamorphosis and whose parable may be summarised by the following pathetic couplet: ‘Ah beauteous beast! Thy cruel fate evinces. How vain the ass that puts its trust in Princes!’.4

Alongside all of the jokes and satire about targeting the Queen and women’s exotic animals in a print culture dominated by a male elite, the zebra represented a deeper dimension in Georgian society which was immersed in a culture of spectatorship. Georgian naturalists initially believed that zebras might be tameable and be trained to pull the carriages of the rich around London. Such a sociable function of the zebra, associated to the Englightment dream of domestication and adaptation, would have added some kind of elegance and variety to Georgian luxuries. Oliver Goldsmith, author of A History of the Earth and Animated Nature (1774), was convinced that zebras might be tameable and converted to the sociable purposes of the horse:

- 3. François Marie Arouet de Voltaire, A Letter from Mr. Voltaire to Mr. Jean Jacques Rousseau (London: Payne, 1766), p. 35.

- 4. ‘William Mason to Horace Walpole, 2 June 1773’, in Warren Hunting Smith and George Lam (eds.), Horace Walpole’s Correspondence 1756-1799 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955), p. 90-91.

‘It is, however, most probable that the zebra, by time and assiduity, might be brought under subjection: for as it resembles the horse in form, it has indisputably a similitude of nature, and only requires the efforts of a skilful and industrious nation to be added to the number of our domestics’.5

- 5. Oliver Goldsmith, A History of the Earth and Animated Nature (London: Fullarton and Co., 1852), vol. I, p. 285.

But the personalities of the Queen’s female zebras, notoriously known for biting, kicking and ungovernable behaviour, disappointed these expectations. There was only one exception as exemplified by the male and gentle zebra at Exeter Change, a menagerie on the Strand, who lost his wildness and let children sit on his back. This rare example of a tamed zebra, making naturalists hope in some kind of service to sociability (racing, hunting, betting and so forth), along with the legacy of Queen Charlotte’s zebra show how the Georgians were deeply fascinated by the zebra. To put it into Christopher Plumb’s words: ‘The zebra, like the electric eel, became an animal used to convey and articulate a wide range of cultural concerns in the late eighteenth century, as well as inspiration for humour and satire. These particular animals were highly conspicuous exotic oddities in Britain in this period, but far more common exotic animals also attracted attention.’6

- 6. Christopher Plumb, The Georgian Menagerie: Exotic Animals in Eighteenth-Century London (London: I.B. Tauris, 2015), p. 193.

The Sociability of Travelling Menageries: Gilbert Pidcock’s Well-Behaved Exotic Animals

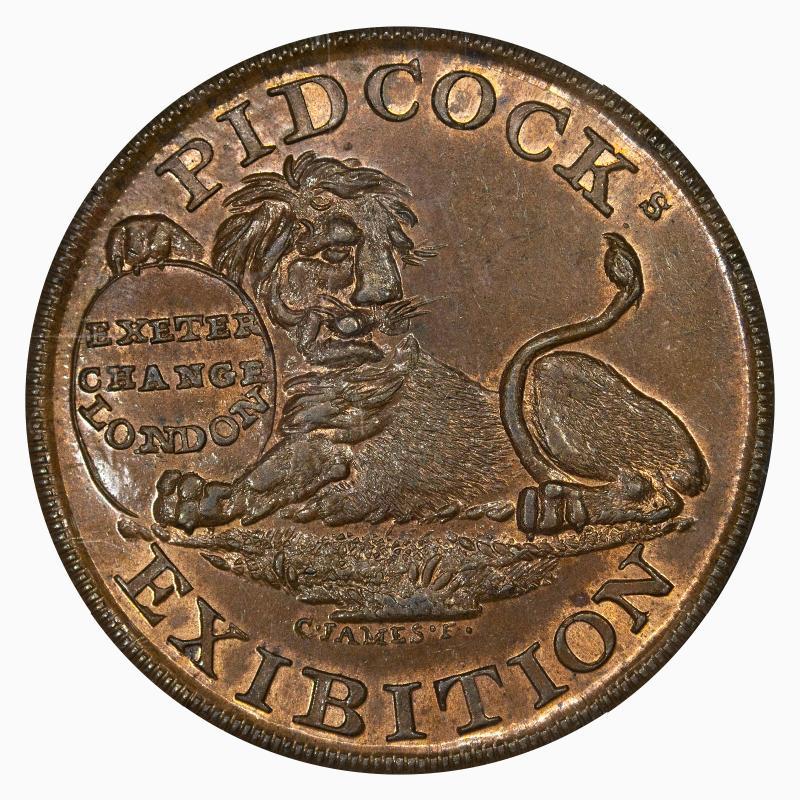

Apart from royal menageries providing entertainment and prestige, a peculiar place of sociability was the travelling menagerie, also known as the Beast Show, described as an itinerant animal exhibition run by showmen whose aim was to entertain ordinary people. Of all better-known travelling showmen, Polito, Ballard, Miles and Wombwell, Gilbert Pidcock from Derbyshire appears to be the most socially-acclaimed menagerist who purchased in 1793 the famous menagerie at the Exeter Change in the Strand in London.

The latter, a rival to the long-established animal collection at the Tower menagerie, was a two-storey building with many arcaded shops on the ground floor and a large room (the Great Room) in which animals were shown: a parade of elephants, lions, tigers, monkeys, bears and vultures. Spectators could learn more about rare species by purchasing Pidcock’s booklet, The History and Anatomical Description of a Cassowar, from the Isle of Java in the East-Indies: The Greatest Rarity now in Europe which was sold as a souvenir contributing to increase his reputation as practitioner of nature. Brass promotional tokens for Pidcock’s Exhibition ̶ which are some of the most collectable items still on sale today ̶ were also produced functioning to publicise his menagerie as well as to promote businesses. The featured animals on the verso of the tokens – standing elephants, flying eagles, couchant lions, walking antelopes, and so on and so forth – were also heralded in print advertisements describing them sensationally as rare and extraordinary creatures. The following is one of Pidcock’s advertisements emphasising the uniqueness of his collection:

‘GRAND MENAGERIE of WILD BEASTS and BIRDS, all alive, is just arrived, and now exhibiting at the White Lion, Corn-Market, DERBY. This invaluable Collection consists of two Mountain Lion Tygers, Male and Female – two Satyrs, or Ætheopian Savages, ditto – a He Bengal Tyger – a Porcupine – an Ape – a Coata Munda – a Jackall – four Macaws – two Cockatoos, one of which will converse with any Person in Company; with a Number of other Curiosities not inserted.

N.B. The large Beasts are well secured, so that the most timorous may approach them with the greatest Safety.

Admittance 1s. each – a Price by no means adequate to the Variety of Curiosities exhibited.’7

- 7. Derby Mercury (31 Dec. 1789).

Pidcock inserted hundreds of advertisements in London and local newspapers (when he was touring England)8 in order to start a new trend of interaction with animals, inviting the Georgians, including women and children, to touch or ride them. The thrilling experience of a physical proximity with tamed exotic animals was highly advertised as a social and a pleasurable practice stimulating conversation about broader cultural debates. Like the concert, the theatre, and museums, a menagerie fostered discussions about the colonial trade, the exotic, the domestication, the living conditions of animals, since as Habermas explains, ‘anyone has the right to judge’.9

At Pidcock’s Menagerie on the Strand children could ride elephants in an apartment that had been constructed for that purpose. The elephant involved the audience’s participation with closer encounters, performing tricks with coins and handkerchiefs. The public exhibition of elephants brought spectators into close contact with these animals imported from India, whose sagacious minds were intended as expressions of rational and sensitive creatures. The close tactile engagement with elephants represented the encounter with an embodied expression of the Empire reminding the Georgians about the relationship between monarch, parliament and citizens. As a modern Noah, Pidcock was able to gather crowds of spectators flocking to see the boxing Kangaroo, the stupendous elephant sweeping the lawns or the paths with a broom, and the accommodating and indulgent male rhinoceros who bore to be touched on any part of his body. This latter, purchased for £ 700, was so obedient and friendly with strangers that George Stubbs was commissioned to execute a painting in 1724. Thanks to his many talents as a showman, dealer in animals, and advertiser, Pidcock appears to be fostering the sociability of menageries.

- 8. Pidcock started his tour from Warwick, and afterwards he visited the following cities: Oxford, Windsor, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Linlithgow, Falkirk, Durham, Derbyshire, Chelmsford in Essex, Newcastle, Alnwick, south of Hadrian’s Wall, and then back to Edinburgh. In December 1788, Pidcock announced that he was now on his road to London to devote himself to the menagerie at the Exeter Change.

- 9. Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. Thomas Burger (Cambridge: the MIT Press, 1989), p. 40.

The Social Practice of Turtle Dinners

London’s menagerists were first and foremost animal merchants purchasing and selling exotic animals as living commodities whose peculiar qualities were employed as ingredients to prepare elite delicacies, exotic fragrances and highly refined hair products epitomising luxury, gentility and respectability. In particular, the Georgians developed a real mania for the exotic turtle which was imported from the plantations and colonies in the Caribbean. Described as an expensive delicacy for the few, i.e. aristocrats and aldermen (a pound of turtle was typically priced between one and two shillings, which was equivalent to the daily wage of a manual labourer), the turtle was considered to be a means to secure social relationship. Gentlemen attending the club used to eat turtle with sobriety in amiable fellowship. The dinner registers of the Royal Society’s dining club attest the importance of turtle in socialising. The donation of a turtle was seen as a means of enhancing a gentleman’s reputation to the extent that any member donating a turtle annually, would become an Honorary Member. The turtle soup, whose recipe was illustrated in Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1747), was a delicacy characterised by its specialised tableware, chisels, assorted instruments, and tureen in the form of a turtle. According to Georgian polite table etiquette, the serving of turtle soup at the beginning of the dinner was a ‘conversation starter and distraction between the first soup course and the second more substantial course’ (Plumb 73).

Opposed to the sobriety and temperance of turtle dinners at the Royal Society, there were the turtle feasts organised by the city aldermen whose gluttony and voracity soon became the object of satire in the late eighteenth century. Accounts of exotic foodstuffs could be found in The London Magazine (1755) in which the world of turtle eating was connoted as monstrous, macabre and corrupted. Satirical representations of turtle feasts were reproduced by caricaturists (William Dent), dramatists (Samuel Foote), and playwrights (William Kenrick) targeting the city’s merchants, bankers and the decline of aristocratic families. The taste for turtle flesh was such a prominent and controversial mania that a satirical alderman character named ‘Mr Turtle’ appeared in news columns and editorials.

The Comfort of Menageries and Social Exotic Scents

The sociability of the eighteenth-century menagerie was also enacted by the malodour and sweet smells deriving from exotic animals. Those menagerists who conducted exotic-animal business were supposed to accommodate animals in comfortable, clean, well-ventilated dens in order to receive visitors. A sensitivity to odour was valued as an expression of gentility, refinement, politeness and good manners. The Georgian domestic obsession with comfort was equally applied to menageries whose comfort was, of course, for the benefit of human visitors. Advertisements reassuring ladies about the smell of strange animals appeared in newspapers conveying the idea that the spectatorship of animals was connected to a pleasurable sensation. A case in point was a newspaper commentary about the camels’ breath printed in 1758 in Mist’s Journal: ‘The ladies are especially charmed with them; and express great satisfaction at the sweetness of their breath, and the neatness of their apartment’.10 Richard Happenstall, a shrewd showman touring England with a dromedary from Persia and a camel from Grand Cairo, informed the lovers of living curiosities that they might admire his exotic animals at the Talbot Inn on the Strand between December 1757 and May 1758.

- 10. ‘Dromedary and Camel’, advertisement, 26 January 1758; Mist’s Journal, cutting, 5 April 1758, Lysons Collection, British Library, microfilm MC20452, frames 9 and 8e.

This appreciation of animal aromas was extended to animals such as the civet whose waxy yellow-brown secretion exuded a strong musky odour. Perfumes and wig powders were made with civet epitomising luxury, decadence and sensuality for much of the eighteenth century. Both an aphrodisiac and a perfume, civet was perhaps one of the most expensive goods of the Georgian period. The cost for ounce of civet was 40 shillings and in order to produce a perfume between 20 and 40 grains of civet were needed. Daniel Defoe apparently purchased from John Barksdale 70 civets for £ 850 thinking they were profitable goods even though he disliked them to the extent that he defined them as ‘furious wild cats’.11 He actually paid only £ 200 ̶ that he borrowed from his friend Samuel Stancliffe to whom he already owed £ 1,100 ̶ and some promissory notes to Barksdale. The long list of Defoe’s unsolved payments, including the amount due for civet cats, led to his being arrested at the Fleet Prison. Unexpectedly, civet perfumes went out of fashion due to the substantial shift in attitudes of Georgian Londoners towards cleanliness and hygiene. The olfactory tolerance of people, used to the smell of burning sea coal clouding the city in smog, changed radically and pungent civet-based perfumes were replaced by florally fragranced perfumes. As Henri Lefevbre aptly summarises, ‘the sense of smell had its glory days when animality still predominated over “culture”, rationality and education’.12

Another malodorous exotic good was the bear grease combed as a wax and used to fix powder to wigs, commonly known as hallmarks of gentility and respectability. With this superior product, Georgians not only disguised any kind of disease as well as the signs of aging, but they also kept clean. Grease traders used to mask the intolerable smell of bear grease with the pleasant scents of rose or lavender oil while the barbers used to clean it prior to boiling. As for the civet, the grease dealers exhibited the killed bears hung on chains in the windows and invited the customers to witness the removal of the fat in person in order to attest the quality and veracity of the product which, more often than not, was replaced with pig fat. The sending of a servant as a witness of the cutting of the fat was necessary to ensure the authenticity of such a luxury good. In the reign of George III, bears were imported from North America and Russia and were mainly exhibited in the Tower. Dancing and performing bears walked the streets of London and were also kept alive at barbers’ shops (Mr Money and Mr Macapline were rival bear dealers) until they decided it was time to kill bears to provide grease for their business. The co-existence of hairdressers, customers, and bears confined in a shop eventually resulted in tragic and horrific events. A well tamed and behaved bear belonging to Mr Bradbury, who took the animal with him in taverns and parties for monetary reasons, one night escaped from his brick shed in a yard terrorising the city with his furious roaring. The bear attacked a 13-year old boy tearing off the back of his head without killing him thanks to a crowd confronting the wild animal who ultimately was shot and his head was split in two by a soldier with a spade. Horrific stories of bears assaulting people were also reported from the Tower where a brown bear was slaughtered on the order of the Prince of Wales in 1782 after he had nearly killed the Keeper’s wife who had inadvertently left the door of his cage open.

The Macabre Sociability of the Crowd

During the long eighteenth century animal accidents were reported as horrific accounts in newsprint or scattered broadsides. Seen as cautionary tales to others, reports of exotic animal accidents appealed to the Georgians’ taste of fear and horrific amusement. Unable to restrain their curiosity and their need of close proximity with wild beasts, the Georgians might be mauled by lions, tigers and panthers, suffocated by an elephant, or even poisoned by a rattlesnake. A series of unfortunate events occured at the Tower Menagerie as well as at George Wombwell’s travelling menagerie and at the Exeter Exchange owned by John Cross. Monkeys were notorious for attacking and lacerating young boys at the Tower Menagerie whose resident panther, Miss Lucy, was advertised in the guidebook for tearing the arms of women attempting to be familiar with her.

The most terrific wild beast at George Wombwell’s travelling menagerie, was Wallace the lion whose ferocious attacks featured prolifically in newsprint between the 1820’s and the 1830’s. The bloody stories about the lion’s untameable behaviour mentioned the long list of people, including his keeper Jonathan Wilson, who lost hands and limbs due to their carelessness when approaching the animal. But even more horrific was the story reported in the Northampton Herald’s, according to which Wallace and a tiger escaped one night from a damaged cart in Derbyshire. The case of a man, a woman with a child in her arms and the 11-year-old boy who were killed by Wallace and the tiger before their capture was classified as accidental death.

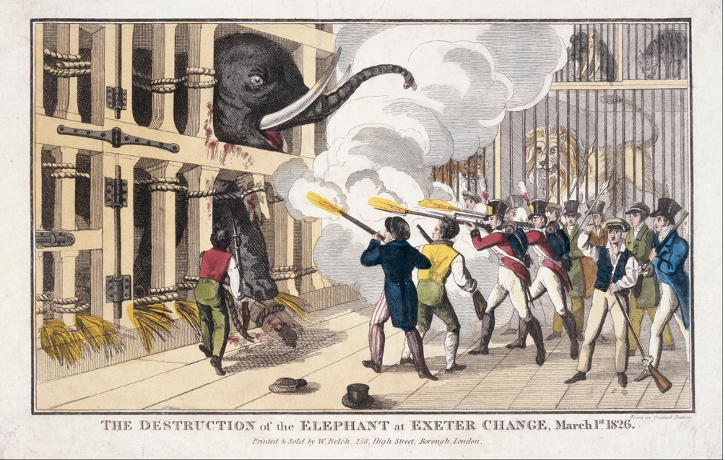

A most horrific anecdote of animal abuse was committed against Chunee, a 7-ton elephant from Bengal purchased by Mr Harris, the manager of Covent Garden Theatre, to perform in a grand pantomime known as the Harlequin and Padmanaba, or the Golden Fish. If in 1813 Chunee appeared to be the most popular attraction at the Exeter Change in Polito’s time, so well-behaved that Lord Byron wished he was ‘his own butler’ (14 November 1813), then towards the end of his life, he became dangerously violent due to his rotten tusk and a bad toothache. On 26 February 1826, while on his usual Sunday walk, he killed one of his keepers, John Tietjen. The following days he resulted increasingly enraged and so difficult to handle over that it was decided to end his life. The spectacular and awful death of Chunee the elephant in 1826 is the single most reported event in the history of the menagerie at the Exeter Change, but it was the climax of many years of mistreatment, in particular the total lack of exercise and confinement in a cage in which he could barely turn round. A regiment of soldiers were summoned to shoot him with 152 musket balls and one final sword stroke.

Hundreds of people paid the usual shilling entrance fee to see his carcass butchered, and later dissected by doctors from the Royal College of Surgeons. Chunee’s death was publicised with illustrations reproducing his bleeding 4-ton body which was rumoured to be sold to butchers serving large steaks at the menagerie. Not only did his death spark protests over animal rights, as exemplified by the letters published in The Times (10 March 1826) criticising the barbarity of the process, but it also stimulated reflections about menagerie manners. Spectators needed to develop a more disciplined behaviour around animals, a polite engagement avoiding improper and intrusive attitudes as a form of deep respect for animals. After Chunee's death the menagerie at Exeter Exchange declined in popularity and the building was demolished in 1829 marking the end of an era and thereby paving the way for nineteenth-century zoological gardens. Like concerts, theatres and museums, menageries institutionalised the exotic with discussions in newspapers, letters, diaries, trade cards, jokes, novels and natural history books which became the medium through which Georgians appropriated and tamed the exotic epitomised by roaring sounds echoing through the streets of eighteenth-century London.

As a typical urban phenomenon, menageries were places of sociability exploiting the exoticism of animals becoming luxury commodities to be exhibited publicly or to be consumed collectively. New social practices emerged as a result of the maniacal attraction for exotic animals satisfying the eighteenth-century curiosity for the animal world.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Anon., ‘A Humourous Account of a Turtle Feast and a Turtle Eater,’ The World n° 123, May 8, 1755.

Bennett, Edward Turner, The Tower Menagerie: Comprising the Natural History of the Animals Contained in the Establishment with Anecdotes of their Characters and History (Chiswick: Whittingham, 1829).

Grigson, Caroline, Menagerie: The History of Exotic Animals in England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

Henry, David, A Historical Account of the Curiosities of London and Westminster (London: Newbery, 1769).

Kirkby, Diane and Luckins, Tanja, Dining on Turtles: Food Feasts and Drinking in History (London: Palgrave, 2007).

Pidcock, Gilbert, The History and Anatomical Description of a Cassowar, from the Isle of Java in the East-Indies: The Greatest Rarity Now in Europe (Bury: W. Green, 1778).

Plumb, Christopher and Shaw, Samuel, Zebra (London: Reaktion, 2018).

Rennie, James, The Menageries: Quadrupeds Described and Drawn from Living Subjects (London: Charles Knight, 1831).

Tullet, William, Smell in Eighteenth-Century England: A Social Sense (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).