Résumé

The upper class of Philadelphia—a political, economic, and cultural center in eighteenth-century British North America—followed English patterns of sociability in order to distinguish themselves in colonial society and to mix in British circles. Refinement of one’s person, and opportunities to display this in select groups, were essential to elite distinction, making establishment of a Philadelphia Dancing Assembly a desideratum. Founded in 1749, the Assembly thrived, even into the early Federal period. Rules governing all aspects of participation, including the dancing itself, sustained the Assembly’s role in determining class status and creating social ties among colonial and early-national social elites.

Mots-clés

For many in British North America’s upper and aspiring classes during the eighteenth century, the English social world was the model for refined behavior.1 It should be noted that most people living in these colonies in this period had other notions than England for their ‘mother’ country: Native Americans, African-descended people, and European settlers from Germany or Ireland sought to sustain their own social and cultural practices. Encounters among these populations contributed to shifts—including in corporeal understandings—that Americans were undergoing. Culturally, however, many of the colonies’—and then the nation’s—visible institutions (from banks to ballrooms) closely resembled those of England. The City Dancing Assembly of Philadelphia was one such bastion of gentility, creating a consciously exclusive social sphere of individuals with appropriately trained bodies and behaviors. A populous port, commercial hub, and political hotbed, Philadelphia was, by the mid-eighteenth century, the second city of the British Empire, making its social weight significant within the colonies and beyond. Of this, the city’s established and aspiring elites were well aware.2

- 1. Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP) Cadwalader Collection, ‘Genealogical History of Thomas Willing’, (n.d.); Richard Bushman, ‘American High-Style and Vernacular Cultures’, in Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole (eds.), Colonial British America: Essays in the New History of the Early Modern Era (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), p. 345-83.

- 2. E. Digby Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1979).

William Penn, a wealthy Quaker dissident, gained a royal charter in 1681 for a vast territory across what is now Pennsylvania. Its capital city, Philadelphia, was intended to demonstrate in layout and laws the values of rationality, pacifism, austerity, and tolerance—tolerance for religious diversity, but not for frivolity or amusements. Stringent Quaker morality shunned theatre, dancing, and other convivial entertainments. Yet the colony’s religious diversity meant that those with different views arrived and disputed Quaker asceticism. Too, the Quakers’ enterprising industry brought wealth to many, which often led to relaxing of strict personal standards. Still, pressures of Quaker morality left Philadelphia with ‘little gaiety and less elegance’.3

- 3. Carl and Jessica Bridenbaugh, Rebels and Gentlemen. Philadelphia in the Age of Franklin (New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, 1942), p. 2.

Thus, the city’s thriving merchants, bankers, and professionals sought a social scene commensurate with their wealth and contacts abroad. Dancing masters appeared to teach Philadelphians the appropriate grace and deportment for such status. In the 1720s and 1730s, masters including Samuel Perpoint, Thomas Ball and sister, and Theobold Hackett4 advertised dancing as refinement, promising to teach adults and children grace of carriage and genteel behaviors, along with the latest dances popular in England and on the Continent. By 1748, Philadelphians could display their deportment and fine dancing in the City Dancing Assembly, a subscriber-only gathering. The new assembly’s gentility was recognized in England: Walter Ewer wrote in 1753 from London to cousin William Sword in Philadelphia to ask if William attended the Dancing Assembly, which Ewer had heard was ‘a fine one.’5

- 4. Perpoint’s notices were in the Pennsylvania Mercury, according to Joseph E. Marks, American Learns to Dance (New York: Dance Horizons, 1957), p. 39. Ball’s advertisements were in the Pennsylvania Gazette (Mar. 5, 1730); Hackett’s in Pennsylvania Gazette in August 1738.

- 5. HSP Sword Family Papers, Letters, 18 Aug. 1753.

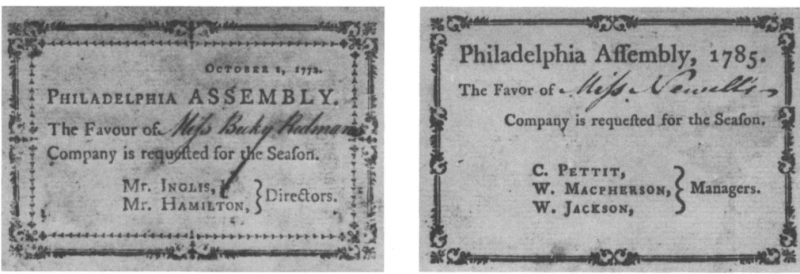

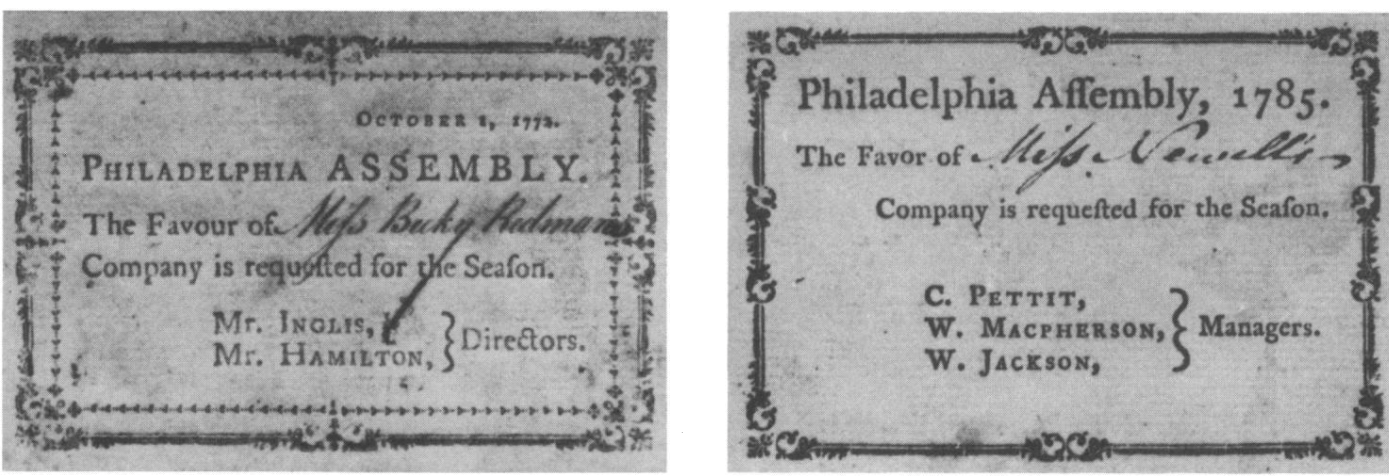

Even pleasure in the Quaker City would be rationally regulated. Founders moderated the Philadelphia Assembly more strictly than those of London or Bath, governing its meetings, management, tickets, and more. Rules were occasionally reinforced, perhaps to bolster managers’ authority against more democratic portions of the young nation’s populace. Strangers were barred from admission, keeping artisans, mechanics, and shopkeepers out. Welcomed on a plane of elevated sociability were merchants, landholders, bankers, mayors, governors, and even a few church ministers.6 Initially, ladies were admitted free, with a subscriber’s invitation. In addition to dancing and sociable conversation, the assemblies offered card tables and a light collation for refreshment in the course of each evening.

- 6. HSP AM 3075, docs. 1-5, 1748-49.

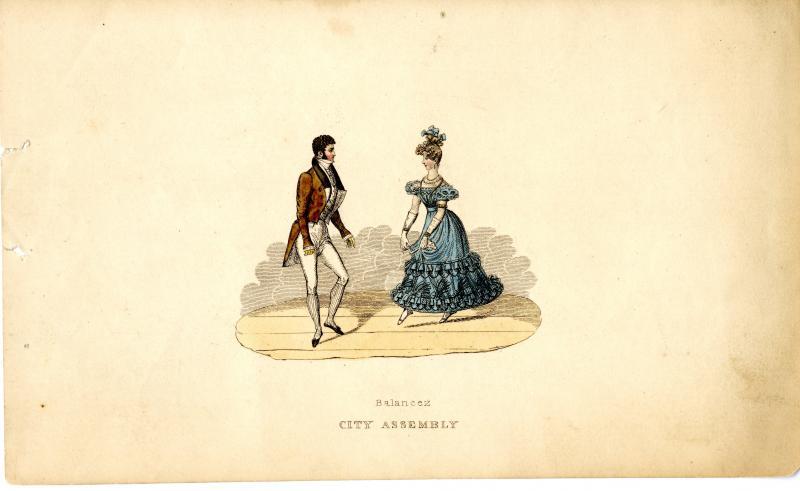

The specific dances performed at each Assembly were determined by the managers. The minuet formally opened any elite ball, danced by one couple, in order of social status, as others watched. Having passed through this performative opening, the company enjoyed the more convivial country dances, either as longways or quadrilles of four couples. A participant recalled these early days when ‘we had no spice of French in our institutions, and consequently did not know how to romp in cotillions,’ referring to the French quadrilles popular in England and the colonies later in the eighteenth century; rather, attendees ‘moved with measured dignity in grave minuets or gayer country dances.’7 Assembly rules required that each set, formed in order of dancers’ arrival, have ten couples; if a set came up short, its couples could be assigned to other sets, since many longways dances were democratically choreographed ‘for as many as will,’ allowing participants to pass up and down the line and engage, if briefly, with dancers other than their partners.

- 7. James Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Times (Philadelphia: Carey & Hart, 1845), v. I, p. 237.

Most country dances performed at these early gatherings were English, taught by English masters, who boasted connections to England and other European countries. In 1753, for example, John Ormsby informed those interested in his school of fencing and dancing that he ‘has had the honour to tutor several gentlemen and ladies of the first rank in different parts of Europe.’8 He prepared students for ‘a discreet and courteous behavior, a genteel easy carriage,’ allowing them ‘to appear in the politest company.’ Others—George Abington in 1758 and John Baptiste Tioli in 1763—advertised in the Pennsylvania Gazette their connections to professional theatres, particularly those in London. Such claims might appeal to some clients, but would surely deeply offend those suspicious of the vices they saw inherent in the theatre.

- 8. Pennsylvania Gazette (January 1753).

The Quaker fathers were not silent as dancing masters, the Dancing Assembly, and even a public theatre appeared in the city, yet genteel institutions and public amusements could not be suppressed. Rather, they seemed contagious: small towns like Lancaster, Pennsylvania, sought to emulate Philadelphia’s social life by advertising for a dancing master to come to their town, where he ‘may expect to meet with due Encouragement.’9 Soon, Lancaster had its own Dancing Assembly. In the 1770s, dancing masters’ advertisements shifted from the general promise of corporeal refinement through dance to the specifics of teaching minuets, hornpipes, cotillions, and country dances, ‘as practiced in the most polite Assemblies in Europe.’10 Englishmen and other Europeans traveling in America, and Americans abroad, could share the bodily language of polite behavior and elegant social dancing.

England remained the epicenter of elite Americans’ social aspirations, but as the colonies moved toward political independence, they sought their own values. In the early years of the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress, seated at Philadelphia, discouraged ‘every species of extravagance and dissipation,’ including dancing. Still, Philadelphia was the gathering place of political leaders and their households from all the colonies, and many—like General George Washington, an enthusiastic dancer—were used to polite entertainments. Thus, neither dancing masters nor Assembly disappeared; rather, with Philadelphia’s central political and strategic role, the opportunity the ballroom offered for elite exchanges became critical to communications, social bonding, and much-needed diversion.11

- 11. For example, a letter from Major Samuel Shaw to his friend Winthrop Sargeant indicates the passage of letters at such Dancing Assemblies during the Revolution (HSP Society Miscellaneous Collection, Shaw letter, 3 May 1780).

One French visitor, the Marquis de Chastellux, viewed Assembly gatherings as ‘methodical amusements’12 —reflecting Quaker influence on the city’s sociality. Partners at each ball were chosen by the managers, who in these times of war were military officers. They distributed numbered ‘billets’ to each lady and gentleman, who were then, by ‘fate,’ assigned to one another as the numbers matched. The dances reflected wartime events and current politics, with titles like ‘The Success of the Campaign,’ ‘The Defeat of Burgoyne,’ and ‘Clinton's Retreat.’ Americans were dancing their own choreographies; at one of Gen. Washington’s balls, a Native-American theme was evident in costume accessories and music, which included a rattle, knife, and pipe.13 Chastellux also noted the marked exclusion of Tory attendees (British sympathizers) at Assemblies. Dancing masters worked to adapt to the changing climate and social order. Thomas Pike, for example, graciously acknowledged in his advertisement that, in the new society, some ‘had not an opportunity of learning to dance very young,’ and for these aspirants to higher-class status, Pike offered to teach ‘a genteel address, with a proper carriage,’ if they shunned the extravagance of dancing.14

- 12. Marquis François Jean de Chastellux, Travels in North America in the Years 1780, 1781, & 1782 (London: G. G. J. & J. Robinson, 1787), p. 314-17.

- 13. John W. Jordan, ‘Adam Hubley, Jr., Lt. Col. Commandant 11th Penna. Regt., His Journal, Commencing at Wyoming, July 30th, 1779’, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (1909), p. 420.

- 14. Pike advertised in the Pennsylvania Gazette at various times from September 1774 to January 1776. On Pike, see Judith Cobau, ‘The Precarious Life of Thomas Pike, A Colonial Dancing Master in Charleston and Philadelphia’, Dance Chronicle (vol. 17, n° 3, 1994), p. 229-262.

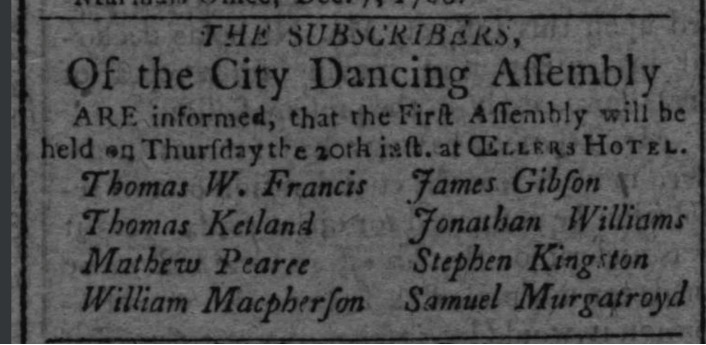

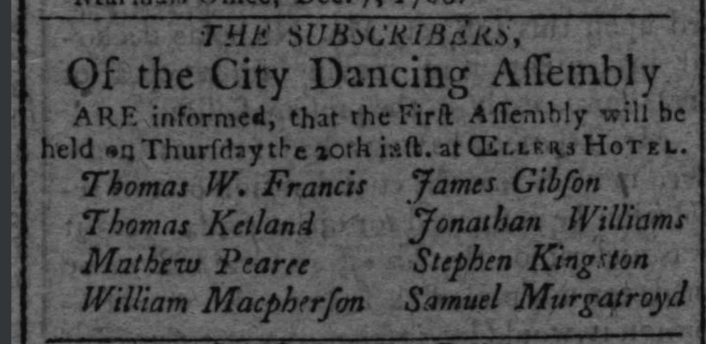

After the war, when Philadelphia served as site of the Constitutional Convention and then as the nation’s capital, the city saw a lively social scene, despite ongoing Quaker efforts to suppress amusements. The Dancing Assembly sprang into full bloom, hosting the nation’s first families at the elegant City Tavern, and later at O’Eller’s Hotel, which became the center of fashionable life. There, in 1794, occurred one of the earliest balls celebrating Washington’s birthday, which took the place as an annual social and political event of the King’s birthday ball.

A noticeable development in the later eighteenth century was appearance in Philadelphia and other U.S. cities of dancing masters with French names. The revolutions in France and in what had been France’s territory of Haiti (Saint-Domingue), brought waves of French refugees to the United States, with Philadelphia a major magnet, as it had long been for immigrants.15 As early as 1783, M. Cenas offered dancing lessons and ‘the Encyclopedia’ in its latest edition. He taught in Philadelphia for eleven years, giving private lessons at President Washington’s home. In the 1790s, Cenas’ countrymen M. D. Duport, James Robardet, and M. Sicard, among others, joined the competitive market for elevating Philadelphians’ social graces through dancing and deportment instruction. Yet another dancing master sold his lessons on the advantages dancing offered ‘to health, and to growth,’ by ‘strengthen[ing] the limbs and render[ing] them fit for their proper exertion,’16 for in the new nation, health and strength of body counted among the most desired personal graces. At the same time, the advertisement assured potential clients, dancing ‘enables young people to join in a diversion, which, in decent company, is as innocent as it is pleasing.’

- 15. Maureen Costonis, ‘Ballet Comes to America, 1792-1842: French Contributions to the Establishment of Theatrical Dance in New Orleans and Philadelphia’ (PhD dissertation, New York University, 1989), p. 148. Since Cenas’s notices gave no further specification, I assume he was offering an edition of the Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert and published in Paris between 1751 and 1772.

- 16. Andrew Brown, advertising in the Pennsylvania Packet (17 Dec. 1784).

So pleasing was it that enterprising Philadelphia printers began publishing American dance texts, including The American Ladies Pocket Books of 1797 and ’99, with ‘New Country Dances’; and Pierre Duport’s United States Country Dances. Philadelphians also purchased dance books from England, but the borrowing began to go both ways, as indicated by the example of Twenty Four American Country Dances as Danced by the British during their Winter Quarters at Philadelphia, New York, & Charles Town, ‘now Danc[ed] for the first time in Britain.’17 American influence began seeping across the ocean, against the flood in the opposite direction.

- 17. Published in 1785 in London by Longman and Broderip.

English dancing masters persisted alongside the French. William Francis, of the city’s Chestnut St. Theatre, was a fine English comic actor who also specialized in pantomime and dance. Beginning in the 1790s and continuing into the early 1800s, he taught a dancing school in Philadelphia, sometimes partnering with dancer James Byrne, former ballet master at Covent Garden. Francis taught ‘the stately minuet,’ the ‘English country dance,’ and later, the ‘French cotillion,’18 and he published his own dance collection. Reports of Mr. Francis’s balls note his meticulous observance of proper decorum, as well as his gracious joviality. He, and other city dancing masters, learned to appeal to the elite as well as to the aspiring, to meet moral scruples about dancing as a form of sociability, to contribute their own choreographies to the international social-dance repertoire, and in the early nineteenth century, to welcome native U.S. teachers into their ranks. This international cadre of dancing masters helped to sustain the Philadelphia Dancing Assembly into and through the nineteenth century.

- 18. Charles Durang, History of the Philadelphia Stage (Philadelphia: Thompson Westcott, 1868), v. 2, ch. 30, p. 228.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Balch, Thomas Willing, The Philadelphia Dancing Assemblies (Philadelphia: Allen, Lane & Scott, 1916).

Brooks, Lynn, ‘The Philadelphia Dancing Assembly in the Eighteenth Century’, Dance Research Journal (vol. 21, no 1, Spr. 1989), p. 1-7.

Brooks, Lynn, ‘Emblem of Gaiety, Love, and Legislation: Dance in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia’, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (vol. CXV, no 1, January 1991), p. 63-88.

Sims, Joseph P. (ed.), The Philadelphia Assemblies 1748-1948 (Philadelphia: Managers of the Philadelphia Assembly, 1948).

Van Winkle Keller, Kate, George Washington: A Biography in Social Dance (Sandy Hook, CT: Hendrickson Group, 1998).

Van Winkle Keller, Kate, Dance and its Music in America, 1528-1789 (Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2007).