Quote

"... the French for these last fifty years hath been polishing as much as it will bear, and appears to be declining by the natural inconstancy of that people, and the affectation of some late authors to introduce and multiply cant words, which is the most ruinous corruption in any language."

Keywords

To examine into the several circumstances by which the language of a country may be altered, would force me to enter into a wide field. I shall only observe, that the Latin, the French, and the English, seem to have undergone the same fortune. The first, from the days of Romulus to those of Julius Cæsar, suffered perpetual changes : and by what we meet in those authors who occasionally speak on that subject, as well as from certain fragments of old laws, it is manifest that the Latin three hundred years before Tully was as unintelligible in his time, as the English and French of the fame period are now; and these two have changed as much since William the Conqueror (which is but little less than seven hundred years) as the Latin appears to have done in the like term. Whether our language or the French will decline as fast as the Roman did, is a question, that would perhaps admit more debate than it is worth. There were many reasons for the corruptions of the last: as, the change of their government to a tyranny, which ruined the study of eloquence, there being no further use or encouragement for popular orators: their giving not only the freedom of the city, but capacity for employments, to several towns in Gaul, Spain and Germany , and other distant parts, as far as Asia; which brought a great number of foreign pretenders into Rome: the slavish disposition of the senate and people, by which the wit and eloquence of the age were wholly turned into panegyrick, the most barren of all subjects: the great corruption of manners, and introduction of foreign luxury, with foreign terms to express it, with several others, that might be assigned; not to mention those invasions from the Goths and Vandals which are too obvious to insist on.

The roman language arrived at great perfection, before it began to decay: and the French for these last fifty years hath been polishing as much as it will bear, and appears to be declining by the natural inconstancy of that people, and the affectation of some late authors to introduce and multiply cant words, which is the most ruinous corruption in any language. La Bruyere a late celebrated writer among them, makes use of many new terms, which are not to be found in any of the common dictionaries before his time. But the English tongue is not arrived to such a degree of perfection, as to make us apprehend any thoughts of its de cay ; and if it were once refined to a certain standard, perhaps there might be ways found out to fix it for ever, or at least till we are invaded and made a conquest by some other state; and even then our best writings might probably be preserved with care, and grow into esteem, and the authors have a chance for immortality.

But without such great revolutions as these (to which we are, I think, less subject than kingdoms upon the continent) I see no absolute necessity why any language should be perpetually changing; for we find many examples to the contrary. From Homer to Plutarch are above a thousand years; so long at least the purity of the Greek tongue may be allowed to last and we know not how far before. The Grecians spread their colonies round all the coasts of Asia Mirnor, even to the Northern parts lying towards the Euxine, in every island of the Ægæan sea, and several others in the Mediterranean; where the language was preserved entire for many ages, after they themselves became colonies, to Rome, and till they were over-run by the barbarous nations upon the fall of that Empire. The Chinese have books in their language above two thousand years old, neither have the frequent conquests of the Tartars been able to alter it. The German, Spanish and Italian, have admitted few or no changes for some ages past The other languages of Europe I know nothing of; neither is there any occasion to consider them.

Having taken this compass, I return to those considerations upon our own language, which I would humbly offer your lordship. The period, wherein the English tongue received most improvement, I take to commence with the beginning of queen Elizabeth's reign, and to conclude with the great rebellion in forty-two. ‘Tis true, there was a very ill taste both of style and wit, which prevailed under king James the first; but that seems to have been corrected in the first years of his successor, who, among many other qualifications of an excellent prince, was a great patron of learning. From the civil war to this present time, I am apt to doubt whether the corruptions in our language have not at least equalled the refinements of it; and these corruptions very few of the best authors in our age have wholly escaped. During the usurpation, such an infusion as enthusiastic jargon prevailed in every writing, as was not shaken off in many years after. To this succeeded that licentiousness which entered with the restoration, and from infecting our religion and morals fell to corrupt our language; which last was not like to be much improved by those, who at that time made up the court of king Charles the second; either such, who had followed him in his banishment, or who had been altogether conversant in the dialect as those fanatic times; or young men, who had been educated in the fame country; so that the court, which used to be the standard of propriety and correctness of speech, was then, and, I think, hath ever since continued the worst school in England for that accomplishment ; and so will remain, till better care be taken in the education of our young nobility, that they may set out in to the world with some foundation of literature, in order to qualify them for patterns of politeness. The consequence of this defect upon our language may appear from the plays, and other compositions written for entertainment within fifty years past; filled with a succession of affected phrases, and new conceited words, either borrowed from the current style of the court, or from those, who under the character of men of wit and pleasure pretended to give the law. Many of these refinements have already been long antiquated, and are now hardly intelligible; which is no wonder, when they were the product only of ignorance and caprice.

I have never known this great town without one or more dunces of figure, who had credit enough to give rise to some new word, and propagate it in most conversations though it had neither humour nor significancy. If it struck the present taste, it was soon transferred into the plays and current scribbles of the week, and became an addition to our language; while the men of wit and learning, instead of early obviating such corruptions, were too often seduced to imitate and comply with them.

There is another sett of men, who have contributed very much to the spoiling of the English tongue; I mean the poets from the time of the restoration. These gentlemen, although they could not be insensible how much our language was already overstocked with monosyllables, yet to save time and pains introduced that barbarous custom of abbreviating words, to fit them to the measure of their verses; and this they have frequently done so very injudiciously, as to form such harsh unharmonious sounds, that none but a northern ear could endure : they have joined the most obdurate consonants without one intervening vowel, only to shorten a syllable; and their taste in time became so depraved, that what was at first a poetical license not to be justified, they made their choice, alledging, that the words pronounced at length sounded faint and languid. This was a pretence to take up the same custom in prose; so that most of the books we see now-a-days, are full of those manglings and abbreviations. Instances of this abuse are innumerable: what does your lordship think of the words, drudg’d, dsturb’d, rebuk’d, fledg’d, and a thousand others every where to be met with in prose as well as verse ? Where by leaving, out a vowel to save a syllable we form so jarring a sound, and so difficult; to utter, that I have often wondered how it could ever obtain.

Another cause (and perhaps borrowed, from the former) which hath contributed not a little to the maiming of our language, is a foolish opinion, advanced of late years, that we ought to spell exactly as we speak; which, beside the obvious inconvenience of utterly destroying our etymology, would be a thing we should never fee an end of. Not only the several towns and counties of England have a different way of pronouncing, but even here in London they clip their words after one manner about the court, another in the city, and a third in the suburbs: and in a few years, it is probable, will all differ from themselves, as fancy or fashion shall direct: all which reduced to writing would entirely confound orthography. Yet many people are so fond of this conceit, that it is sometimes a difficult matter to read modern books and pamphlets; where the words are so curtailed, and varied from their original spelling, that whoever hath been used to plain English, will hardly know them by sight.

Several young men at the universities, terribly possessed with the fear of pedantry, run into a worse extreme, and think all politeness to consist in reading the daily trash sent down to them from hence; this they call knowing the world, and reading men and manners. Thus furnished they come up to town, reckon all their errors for accomplishments, borrow the newest sett of phrases; and if they take a pen into their hands, all the odd words they have picked up in a coffee-house, or a gaming ordinary, are produced as flowers of style; and the orthography refined to the utmost, To this we owe those monstrous productions, which under the name of trips, spies, amusements, and other conceited appellations, have over-run us for some years past. To this we owe that strange race of wits, who tell us, they write to the humour of the age. And I wish I could say, these quaint fopperies were wholly absent from graver subjects. In short, I would undertake to shew your lordship several pieces, where the beauties of this kind are so predominant, that with all your skill in languages you could never be able to read or understand them.

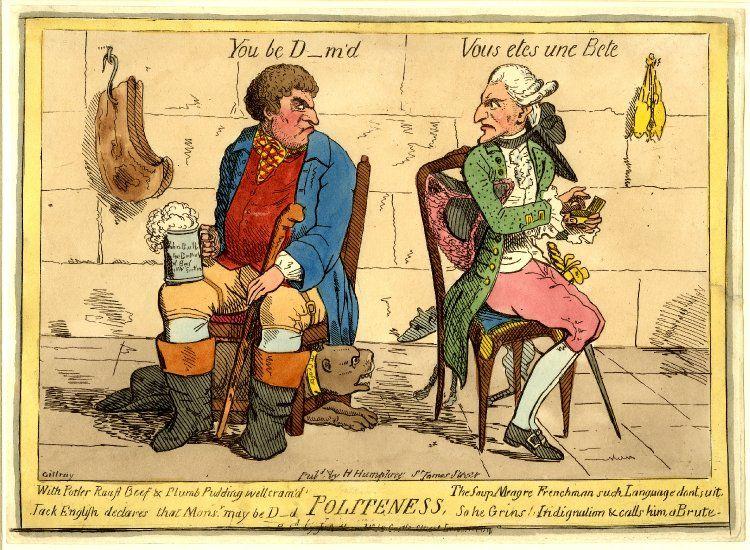

But I am very much mistaken, if many of these false refinements among us do not arise from a principle, which would quite destroy their credit, if it were well understood and considered. For I am afraid, my lord, that with all the real good qualities of our country we are naturally not very polite. This perpetual disposition to shorten our words, by retrenching the vowels, is nothing else but a tendency to lapse into the barbarity of those northern nations, from whom we are descended, and whose languages labour all under the same defect. For it is worthy our observation, that the Spaniards, the French, and the Italians although derived from the same northern ancestors with ourselves, are with the utmost difficulty taught to pronounce our words, which the Swedes and Danes, as well as the Germans and the Dutch, attain to with ease, because our syllables resemble theirs in the roughness and frequency of consonants. Now, as we struggle with an ill climate to improve the nobler kinds of fruits, are at the ex- pence of walls to receive and reverberate the faint rays of the sun, and fence against the northern blasts, we sometimes by the help of a good soil equal the production of warmer countries, who have no need to be at so much cost and care. It it the same thing with respect to the politer arts among us ; and the fame defect of heat which gives a fierceness to our natures, may contribute to that roughness of our language, which bears some analogy to the harsh fruit of colder countries. For I do not reckon that we want a genius more than the rest of our neighbours: but your lordship will be of my opinion, that we ought to struggle with these natural disadvantages as much as we can, and be careful whom we employ, whenever we design to correct them, which is a work that has hitherto been assumed by the least qualified hands. So that if the choice had been left to me, I would rather have trusted the refinement of our language, as far as it relates to sound, to the judgment of the women, than of illiterate court-fops, half-witted poets, and university-boys. For it is plain, that women in their manner of corrupting words do naturally discard the consonants, as we do the vowels. What I am going to tell your lordship appears very trifling : that more than once, where some of both sexes were in company, I have persuaded two or three of each to take a pen, and write down a number of letters joined together, just as it came into their heads ; and upon reading this gibberish, we have found that which the men had wrote, by the frequent encountring of rough consonants, to sound like High-Dutch; and: the other by the women like Italian abounding in vowels and liquids. Now, though I would by no means give ladies the trouble of advising us in the reformation of our language, yet I cannot help thinking, that since they have been left out of all meetings, except parties at play, or where worse designs are carried on, our conversation hath very much degenerated.

Sources

Text taken from Jonathan Swift, A Proposal for Correcting, Improving, and Ascertaining the English Tongue [1712], in The works of Jonathan Swift ... accurately revised ... adorned with copper-plates; with some account of the author's life, and notes historical and explanatory, by John Hawkesworth. London, Printed for C. Bathurst [etc.], 1754-55, vol. 3, p. 323-335. Transcription by Alain Kerhervé. Full volume from HATHITRUST.