Quote

"I had, it seems, the felicity of pleasing everybody that night to an extreme, and my ball, but especially my dress, was the chat of the town for that week, and so the name Roxana was the toast at and about the Court; no other health was to be named with it."

Links to the Encyclopedia:

But to go on with my story as to my way of living. I found, as above, that my living as I did would not answer; that it only brought the fortune-hunters and bites about me, as I have said before, to make a prey of me and my money; and, in short, I was harassed with lovers, beaux, and fops of quality in abundance. But it would not do; I aimed at other things, and was possessed with so vain an opinion of my own beauty, that nothing less than the King himself was in my eye; and this vanity was raised by some words let fall by a person I conversed with, who was perhaps likely enough to have brought such a thing to pass had it been sooner, but that game began to be pretty well over at Court. However, the having mentioned such a thing, it seems, a little too publicly, it brought abundance of people about me, upon a wicked account too.

And now I began to act in a new sphere. The Court was exceeding gay and fine, though fuller of men than of women, the Queen not affecting to be very much in public. On the other hand, it is no slander upon the courtiers to say they were as wicked as anybody in reason could desire them. The King had several mistresses, who were prodigious fine, and there was a glorious show on that side indeed. If the Sovereign gave himself a loose, it could not be expected the rest of the Court should be all saints; so far was it from that, though I would not make it worse than it was, that a woman that had anything agreeable in her appearance could never want followers.

I soon found myself thronged with admirers, and I received visits from some persons of very great figure, who always introduced themselves by the help of an old lady or two who were now become my intimates; and one of than, I understood afterwards, was set to work on purpose to get into my favour, in order to introduce what followed.

The conversation we had was generally courtly but civil. At length some gentlemen proposed to play, and made what they called a party. This, it seems, was a contrivance of one of my female hangers-on, for, as I said, I had two of them, who thought this was the way to introduce people as often as she pleased, and so indeed it was. They played high and stayed late, but begged my pardon, only asked leave to make an appointment for the next night. I was as gay and as well pleased as any of them, and one night told one of the gentlemen, my Lord — — that seeing they were doing me the honour of diverting themselves at my apartment, and desired to be there sometimes, I did not keep a gaming table, but I would give them a little ball the next day if they pleased, which they accepted very willingly.

Accordingly in the evening the gentlemen began to come, where I let them see that I understood very well what such things meant. I had a large dining-room in my apartments, with five other rooms on the same floor, all which I made drawing-rooms for the occasion, having all the beds taken down for the day. In three of these I had tables placed, covered with wine and sweetmeats; the fourth had a green table for play, and the fifth was my own room, where I sat and where I received all the company that came to pay their compliments to me. I was dressed, you may be sure, to all the advantage possible, and had all the jewels on that I was mistress of. My Lord — — to whom I had made the invitation, sent me a set of fine music from the playhouse, and the ladies danced and we began to be very merry, when about eleven o’clock I had notice given me that there were some gentlemen coming in masquerade.

I seemed a little surprised and began to apprehend some disturbance, when my Lord — — perceiving it, spoke to me to be easy, for that there was a party of the Guards at the door which should be ready to prevent any rudeness; and another gentleman gave me a hint as if the King was among the masks. I coloured as red as blood itself could make a face look, and expressed a great surprise. However, there was no going back, so I kept my station in my drawing-room, but with the folding-doors wide open.

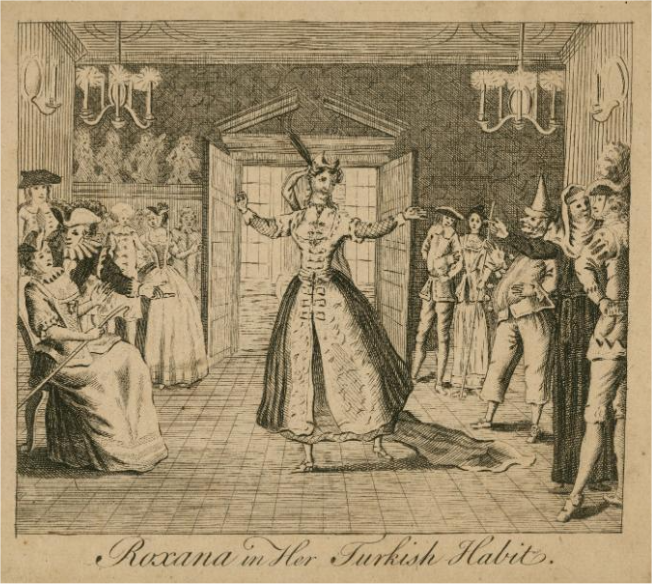

A while after the masks came in and began with a dance à la comique, performing wonderfully indeed. While they were dancing I withdrew, and left a lady to answer for me that I would return immediately. In less than half an hour I returned, dressed in the habit of a Turkish princess, the habit I got at Leghorn when my foreign Prince bought me a Turkish slave, as I have said — the Maltese man-of-war had, it seems, taken a Turkish vessel going from Constantinople to Alexandria, in which were some ladies bound for Grand Cairo in Egypt, and as the ladies were made slaves, so their fine clothes were thus exposed — and with this Turkish slave I bought the rich clothes too. The dress was extraordinary fine indeed, I had bought it as a curiosity, having never seen the like; the robe was a fine Persian or Indian damask, the ground white and the flowers blue and gold, and the train held five yards; the dress under it was a vest of the same, embroidered with gold, and set with some pearls in the work and some turquoise stones; to the vest was a girdle five or six inches wide, after the Turkish mode, and on both ends where it joined or hooked was set with diamonds for eight inches either way, only they were not true diamonds, but nobody knew that but myself.

The turban or head-dress had a pinnacle on the top, but not above five inches, with a piece of loose sarcenet hanging from it, and on the front, just over the forehead, was a good jewel, which I had added to it.

This habit, as above, cost me about sixty pistoles in Italy, but cost much more in the country from whence it came; and little did I think when I bought it that I should put it to such a use as this, though I had dressed myself in it many times by the help of my little Turk, and afterwards between Amy and I, only to see how I looked in it. I had sent her up before to get it ready, and when I came up I had nothing to do but slip it on, and was down in my drawing-room in a little more than a quarter of an hour. When I came there the room was full of company, but I ordered the folding-doors to be shut for a minute or two, till I had received the compliments of the ladies that were in the room, and had given them a full view of my dress.

But my Lord — — who happened to be in the room, slipped out at another door and brought back with him one of the masks, a tall well-shaped person, but who had no name, being all masked, nor would it have been allowed to ask any person’s name on such an occasion. The person spoke in French to me that it was the finest dress he had ever seen, and asked me if he should have the honour to dance with me. I bowed, as giving my consent, but said as I had been a Mohammedan I could not dance after the manner of this country; I supposed their music would not play à la moresque. He answered merrily I had a Christian’s face, and he’d venture it that I could dance like a Christian, adding that so much beauty could not be Mohammedan. Immediately the folding-doors were flung open, and he led me into the room. The company were under the greatest surprise imaginable, the very music stopped awhile to gaze; for the dress was indeed exceedingly surprising, perfectly new, very agreeable, and wonderful rich.

The gentleman, whoever he was, for I never knew, led me only a courant, and then asked me if I had a mind to dance an antic, that is to say, whether I would dance the antic as they had danced in masquerade, or anything by myself. I told him anything else rather, if he pleased; so we danced only two French dances, and he led me to the drawing-room door, when he retired to the rest of the masks. When he left me at the drawing-room door I did not go in, as he thought I would have done, but turned about and showed myself to the whole room, and, calling my woman to me, gave her some directions to the music, by which the company presently understood that I would give them a dance by myself. Immediately all the house rose up and paid me a kind of a compliment by removing back every way to make me room, for the place was exceeding full. The music did not at first hit the tune that I directed, which was a French tune, so I was forced to send my woman to them again, standing all this while at my drawing-room door; but as soon as my woman spoke to them again they played it right, and I, to let them see it was so, stepped forward to the middle of the room. Then they began it again, and I danced by myself a figure which I learnt in France when the Prince de —— desired I would dance for his diversion. It was indeed a very fine figure, invented by a famous master at Paris, for a lady or a gentleman to dance single, but being perfectly new it pleased the company exceedingly, and they all thought it had been Turkish; nay, one gentleman had the folly to expose himself so much as to say, and I think swore too, that he had seen it danced at Constantinople; which was ridiculous enough.

At the finishing the dance the company clapped and almost shouted; and one of the gentlemen cried out, Roxana! Roxana! by — — with an oath, upon which foolish accident I had the name of Roxana presently fixed upon me all over the Court end of town as effectually as if I had been christened Roxana. I had, it seems, the felicity of pleasing everybody that night to an extreme, and my ball, but especially my dress, was the chat of the town for that week, and so the name Roxana was the toast at and about the Court; no other health was to be named with it.

Now things began to work as I would have them, and I began to be very popular as much as I could desire. The ball held till (as well as I was pleased with the show) I was sick of the night; the gentlemen masked went off about three o’clock in the morning, the other gentlemen sat down to play; the music held it out, and some of the ladies were dancing at six in the morning.

But I was mighty eager to know who it was danced with me. Some of the lords went so far as to tell me I was very much honoured in my company. One of them spoke so broad as almost to say it was the King, but I was convinced afterwards it was not; and another replied if he had been His Majesty he should have thought it no dishonour to lead up a Roxana. But to this hour I never knew positively who it was, and by his behaviour I thought he was too young, His Majesty being at that time in an age that might be discovered from a young person even in his dancing.

Sources

Taken from Daniel Defoe, The Fortunate Mistress: Or, A History of the Life and Vast Variety of Fortunes of Mademoiselle de Beleau, Afterwards Call’d the Countess de Wintselsheim, in Germany, Being the Person Known by the Name of the Lady Roxana, in the Time of King Charles II. 1724, p. 210-216. Full book in ECCO.