Abstract

The parole town of Petersfield in Hampshire was one of many towns in Britain that held French prisoners of war during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815). With a large population of over 170 prisoners, Petersfield became a small hub of international sociability that transcended wartime enmities.

In around 1797 an unknown French prisoner of war living in the small Hampshire town of Petersfield wrote down seven verses of La Marseillaise for a local gentleman, Henry Bonham. It is unclear why the verses were written down, but it is possible that Bonham had an interest in French culture and was sympathetic towards the French Revolution. The verses were saved and placed with a number of letters received by Henry Bonham from other French prisoners paroled in the town. Today this small collection of documents forms part of a collection of family papers in Hampshire Records Office offering a brief but vivid insight into the sociabilities between a small group of French prisoners of war and the Bonham family in the 1790s.1

- 1. Hampshire Records Office 94M72/F654/1-19, Bonham-Carter family papers. The collection consists of 16 letters, 2 cards, and the lines of verse. See also, Claire Skinner, ‘The French Connection: Documents about France in Hampshire Records Office’ (Winchester: Hampshire County Council, 1998).

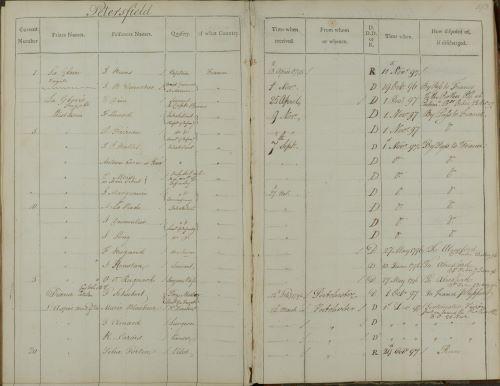

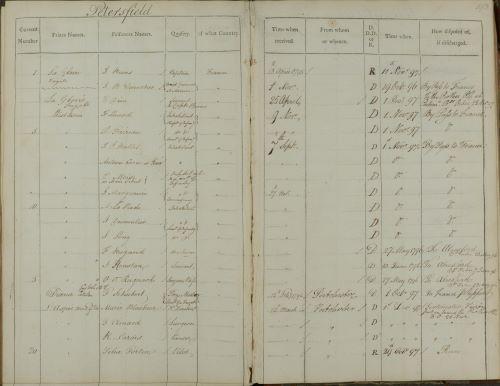

Petersfield was one of many towns in Britain that accommodated prisoners of war during Britain’s war with Revolutionary France and, over a period of four years (1794-1797), more than 170 French prisoners lived in Petersfield. A register of their names still survives today in The National Archives at Kew (see below).2 Only a handful of the individuals who wrote letters to the Bonhams can be identified from this register and it is possible that the record keeping of the towns’ clerks may not have been particularly diligent.

- 2. For an estimate of the town’s population during the 18th century, see Renaud Morieux, ‘French Prisoners of War, Conflicts of Honour, and Social Inversions in England, 1744-1783’, The Historical Journal (n° 56, vol. 1, 2013), p. 55-88.

Henry Bonham and his brother Thomas were local gentlemen who lived in a large house in the centre of Petersfield and, as magistrates and members of the Portsmouth Infantry, both gentlemen played an important role in the local community.3 The brothers used their home for dinners and convivial gatherings and this included individuals from amongst the community of French prisoners in the town. It is possible that by hosting French prisoners of war in their home the Bonhams were using their position in Petersfield society to set an example to others in the community. The large numbers of French prisoners of war arriving in Petersfield during wartime may have caused misgivings among some residents of the town. Linda Colley has noted that the fear of a French invasion during this period was an ever-present anxiety amongst the British population and it was in parole towns like Petersfield that this enemy could be found living amongst the community. As local magistrates it is possible that the Bonhams would be able to calm local anxieties and instead set an example of sociability towards those who may have been perceived as the enemy.4

- 3. Victor Bonham-Carter, In a Liberal Tradition: a social biography 1700-1950 (London: Constable, 1959).

- 4. Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (London: Yale University Press, 2009), p. 5-9; for the limitations of this theory see also Renaud Morieux, Une Mer pour Deux Royaumes: La Manche, Frontière Franco-Anglaise (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2008), p. 17-27.

Prisoners’ reading habits

The Bonhams owned a large library and the letters to Henry Bonham reveal that access to books and reading may have been important to the Petersfield prisoners. Reading was a common cultural activity for both British and French individuals and from the 1750s onwards there had been an expansion in Britain of parish and subscription libraries.5 It is possible that in Petersfield there was no library and the Bonhams’ library would therefore have been an important cultural amenity for the French prisoners.6

Although we do not know what books were in the Bonhams’ library we do know that there was at least one book on English grammar. One prisoner, a M. La Grange, whilst returning some of the books from the Bonhams’ library, asked to keep the ‘Grammar […] in the uncertainty of providing myself with another like it’.7

Another prisoner named Dozouville wrote thanking Henry Bonham for the use of the library and asked if he could be of service to Henry when he returned to France, hinting at how, even in wartime, individuals could establish networks of sociability and goodwill between themselves that could potentially cross borders and transcend national enmities. On the eve of Dozouville’s release and departure to France, the Bonhams sent him a catalogue of their library as a gesture of friendship and, perhaps, as a souvenir of Dozouville’s time in Petersfield.8

- 5. David Allen, Commonplace books and reading in Georgian England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 13-14.

- 6. For the reading habits of French prisoners of war elsewhere in Britain see also Mark Towsey, ‘Imprisoned Reading: French Prisoners of War at the Selkirk Subscription Library, 1811-1814’, in Erica Charters, Eve Rosenhaft, & Hannah Smith (eds.) Civilians and War in Europe 1618–1815 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012), p. 241-261.

- 7. Hampshire Records Office, 94M72/F654/12.

- 8. Hampshire Records Office, 94M72/F654/6.

Financial generosity

The Bonhams also provided financial assistance to a few individuals within Petersfield’s community of paroled prisoners of war. Many of the letters ask for loans of money or hint at financial troubles. One individual, ‘F. Beaudin’, wrote asking for half a guinea and promised to pay back the money either from his parole allowance or by working for the Bonhams. Beaudin went on to explain that he was not used to surviving on the small amount of money that constituted his parole allowance, although by his own admission his parents were also sending him money from France.9

- 9. Hampshire Records Office, 94M72/F654/2.

Another prisoner named Du Roche asked for two or three guineas for himself and his son promising to repay the money as soon as he was back in France. Although there is no record of whether any of the money was repaid another prisoner enclosed a ‘lettre de change’ to his written request for ‘a gesture in this embarrassing situation’.10

- 10. Hampshire Records Office, 94M72/F654/9.

The generosity provided by Henry and his brother made an impression on some amongst the community of prisoners, inspiring at least one of them to help others, or so they wrote. Paroled prisoner Dozouville wrote in a second letter to the Bonhams that he had been helping two other paroled prisoners who were struggling to pay for food and lodgings, adding that he was trying to copy Henry’s example and walk in his footsteps. Henry’s generosity had already, Dozouville wrote, relieved many from amongst the Petersfield community of prisoners of war.11

- 11. Hampshire Records Office, 94M72/F654/4.

Cross channel and diplomatic connections

Contact between the Bonhams and the prisoners of war continued after some were released. Several letters were sent to the Bonhams from France including a letter from a Captain Bedoul in Paris who thanked Henry for all his kindness. Another letter, from a G. Massey in Le Havre, included greetings from his wife and young daughter as well as another former Petersfield prisoner. Massey ended his letter by writing that ‘[…] it will give me infinite pleasure to hear from you occasionally’.12

- 12. Hampshire Records Office, 94M72/F654/7 & Hampshire Records Office 94M72/F654/17.

By supporting the French prisoners in Petersfield, the Bonhams also extended their sociable connections into French diplomatic circles including the French commissaire for prisoners of war, M. Charretié. In May 1797, Charretié wrote thanking Henry for all he had done to support the prisoners, reflecting that that ‘[…] your generous conduct in this occasion & many others, is such as to deserve all praise […]’.13

The letters from the Bonham collection are a reminder of the connections and sociabilities that could be created during wartime. Of course, the Bonham letters are from only a few prisoners from amongst a community of over 170 individuals and many other prisoners left no record of their time in the town. For the men who socialised with the Bonhams the parole town offered a civilised cosmopolitanism that eclipsed the military opposition between Britain and France. Other prisoners of war paroled in the town, particularly the servants of French officers, women, children and people of colour left no surviving written correspondence from which we can read about their lives as prisoners of war in the town. Those lives may always be obscured by others who were able to use their rank and priviledge to create sociable connections that left traces for us to find in the archives today. Despite the limitations of the archive, the Bonham family correspondence does allow us to see how sociability could on occasion transcend both geographical and wartime boundaries. Although, for some, the barriers of social status and rank were perhaps more difficult to overcome than war itself.

- 13. Hampshire Records Office, 94M72/F654/15.

Share

Further Reading

Abell, Francis, Prisoners of War in Britain 1756 to 1815: a record of their lives, their romance and their sufferings (London: Oxford University Press, 1914).

Chamberlain, Paul, Hell Upon Water: Prisoners of War in Britain 1793-1815 (Stroud: The History Press, 2008).

Crimmin, Patricia K., ‘Prisoners of war and British port communities, 1793–1815’, The Northern Mariner/Le marin du nord (n° 6, 1996), p. 17–27.

Daly, Gavin, ‘Napoleon’s lost legions: French prisoners of war in Britain, 1803–1814’, History, (n° 89, 2004), p. 361-80.

Morieux, Renaud, The Society of Prisoners: Anglo-French Wars and Incarceration in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

‘Prisoners of War at Portchester castle’, English Heritage, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/portchester-castle/history-and-stories/portchester-castle-and-prisoners-of-war/.

Schiepers, Sibylle (ed.), Prisoners in War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Online article :

Prisoners of War at Portchester Castle | English Heritage (english-heritage.org.uk)