Abstract

From the mid-seventeenth century until the late nineteenth century, women used tie-on pockets to carry and keep their possessions at hand. Independent from the rest of their clothing, these often capacious pockets were tied around the waist and worn under the petticoat by women of all classes. This short article proposes to see tie-on pockets and their contents as means to explore female mobility and sociability in the long eighteenth century. Eighteenth-century pockets served as containers for various portable objects that acted as props to fashionable sociability and enabled them to navigate social life. Because of their proximity to their owner, pockets were also choice repositories for small personal items. As such they fostered specific modes of female sociability, in particular through the exchange of handmade mementos for the pocket, whilst pockets themselves, another product of female needlework, could sometimes materialise bonds between female friends and kin.

Keywords

When a lady was attacked in London in 1754, her pockets contained ‘among other things’:

‘a small round Tortoiseshell Snuff box, […] a London Almanack, in a black Shagreen Case, […]; an Ivory Carv’d Toothpick Case, […]; a Silver sliding Pencil; a white Cornelian Seal […]; a Tortoiseshell Comb in a Case; a Silver Thimble and Bodkin; a Bunch of Keys, a red Leather Pocket-book; a green knit Purse, containing Half a Guinea, […] with two Glass Smelling Bottles.’1

- 1. Public Advertiser (London), Tuesday March 12th 1754.

The list of objects contained in the pocket by the unknown woman illustrates the role of pockets as carriers of fashionable portable accessories that assisted women’s engagement with various sociable practices in the long eighteenth century. Although not exclusively female, these pocket-sized possessions played a distinctive role in supporting women’s mobility and participation to such fashionable, sociable activities as shopping, visiting, going to assemblies or the theatre. By carrying snuffboxes, scent bottles and portable writing sets, pockets equipped elite women with the wherewithal of polite sociability, expanding the territory of their social engagement, whilst also fostering for all, regardless of wealth, specific modes of female sociability. The exchange of often handmade mementos for the pocket between friends made pockets instruments of female networking for women of all rank and status. Pockets themselves, another product of female needlework, also sometimes materialised bonds between female friends and kin. As objects that were used to carry keepsakes and could be turned into personal mementos, pockets supported specifically female modes of sociability even among humble women whose sociable interactions often attract less historical attention.

Pockets, mobility and fashionable entertainments

Because they could hold cash, entry tickets, fans, opera glasses, snuff, patch and bonbon boxes, etuis, or pocket books, pockets contributed to elite women’s active participation in various sociable activities. Women’s account books and private papers record the use women made of their pockets when out and about. Lady Arabella Furnese, the daughter of the first Earl of Rockingham who married Sir Robert Furnese MP in 1714, had pockets made of silk and fine holland.2 Alongside the purchase of these superior quality pockets, her accounts also show Arabella to have been a voracious consumer of fashionable entertainment. She went to plays, the opera, masquerades, attended assemblies, went to play at cards, bought lottery tickets and regularly took part in raffles. Her appetite for these pleasures entailed much travelling, and there are regular entries in her accounts for ‘chair hir’ for which she would have had to pay with ready money out of her pocket, whilst her pockets supported the small disbursements made along the way that can also be tracked in her accounts.3 Pockets facilitated mobility and engagement with the new pleasures of city life for the wealthy like Arabella. They also furnished accessories for polite interactions and equipped gentry and elite women with tools to navigate various social spaces as well as props allowing for the performative display of fashionable sociability.

The nascent consumer culture was quick to create pocket-sized knick-knacks meant to accessorize fashionable sociability such as a set of natty portable ‘fashionable conversation cards’ advertised in 1791 which gave women appropriate conversational cues in both French and English for drawing-room chit-chat whilst some ladies’ pocketbooks promised ‘upwards of one thousand droll questions and answers […] to create mirth in mixed companies’.4 These portable aides to sociability were typical of the inventiveness of a commercial age where the small place of the pocket was targeted by an ever encroaching market keen to harness any business opportunity.

- 4. Such a pack of conversation cards was advertised in The World (Wednesday 14th December 1791) together with the pocketbook promising the one thousand droll questions and answers.

Although the clever contraptions were targeted at male and female consumers alike, in discourses at least they were often seen as a trope for female vanity. In The Female Spectator in 1745, Eliza Haywood writes:

‘The snuffbox and smelling bottle are pretty trinkets in a lady’s pocket, and are frequently necessary to supply a pause in conversation and on some other occasions, but whatever virtues they are possess’d of, they are all lost by a too constant and familiar use and nothing can be more pernicious to the brain or render one more ridiculous in company than to have either of them perpetually in one’s hand.’5

- 5. Eliza Haywood, The Female Spectator (London, 1745), vol. II, p. 85.

Such portrayal of the nifty portable contraptions being taken out of the pocket in company captures the role such portable accessories played in the performance of sociability – and how they could also be overdone. Although they were kept in the pocket precisely to be taken out, being too constantly out of a lady’s pocket, or too conspicuously manipulated would lead to the worse sociable faux pas: ridicule. The objects carried in the pocket were instrumental to female sociability not solely because of what they enabled – a notebook to jot down engagements, a spy glass to look at the stage or the audience from a distance when at a play – but also because of the subtle choreography that underpinned their use. Possession was not enough, tasteful use and manipulation were also key. Knowing when to retrieve these objects from the pocket as well as being able to activate their diminutive mechanisms were social skills that took part in performances of taste. These in turn were active in creating social connections based on common cultural capital and the shared understanding of the unspoken but potent performativity of material culture.6

Alongside these luxury and semi-luxury contraptions manufactured for the pocket, pockets were choice recipients for small, humbler tokens of friendship exchanged between friends and kin. These often-handmade gifts created other networks of sociability connecting women, whilst pockets also lent themselves to their own practices of sociability among women, whether rich or poor.

- 6. On the material culture and the performance of sociability see Mimi Hellman, ‘Furniture, sociability and the work of leisure in eighteenth-century France’, Eighteenth-Century Studies (vol. 32, n° 4, 1999), p. 415-445.

The pocket as shared space of female sociability

Purses, handkerchiefs, hair lockets or miniature portraits were but a few of the pocket-sized objects that turned the pocket into a shared feminine space where friendship, bonding and female networking processes materialized. Pockets were worn close to the body, in a physical proximity associated by anthropologists with intimacy and sentimental investment.7 This made them privileged receptacles for mementos given by loved ones, the physical closeness of the object mirroring the emotional proximity of donor and recipient. Humble handmade objects such as pincushions, handkerchiefs, needle cases or purses were frequent participants in the traffic of pocket-sized keepsakes between women. In a tender letter to her close friend Jane Pollard dated 1788, Dorothy Wordsworth writes:

- 7. Edward Twitchell Hall, The Hidden Dimension, Man’s Use of Space in Public and Private (London: Bodley Head, 1969).

‘I have got the handkerchief in my pocket that you made and marked for me, I have just this moment pull’d it out to admire the letters. Oh! Jane! It is a valuable handkerchief. […] Adieu my love, do not forget to send me a piece of hair.’8

- 8. William & Dorothy Wordsworth, The Early Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth (1787-1805), ed. Ernest de Sélincourt [1935] (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967), p. 16–17.

The pocket, as the chosen repository for the handkerchief that Jane has made and marked for her friend, is integral to a gift economy characterized by reciprocation.9

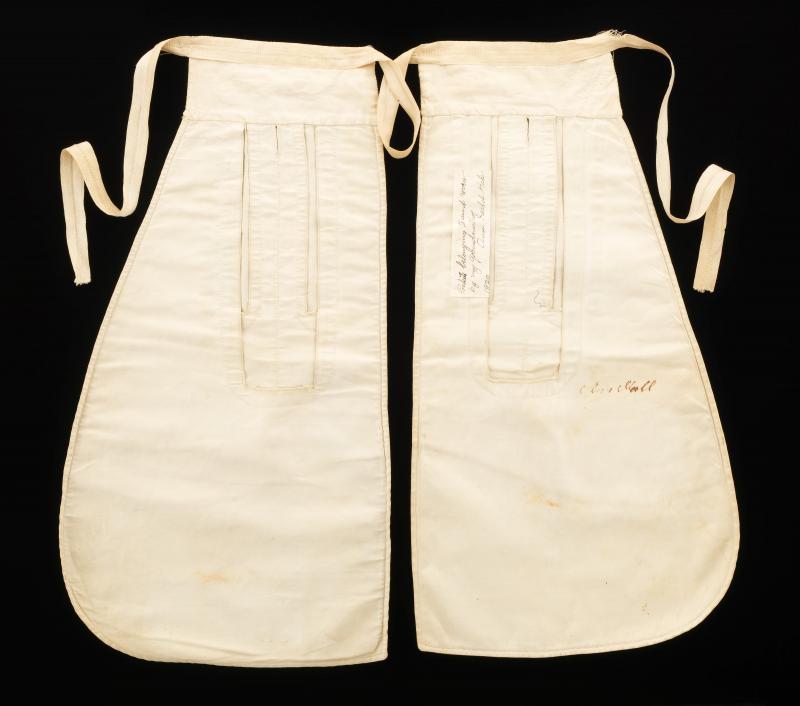

Sometimes it was the pockets themselves that were part of the currency of female friendship and bonding such as when Hannah Lord, in her 1787 will, left a pair of dark calico pockets, white dimity pockets, a patch pocket, a pair of pockets each to a different female friend.10 Some extant pockets still carry the marks of serving as mnemonic embodiments of those who had worn them like a pocket that came with a handwritten note saying it used to be worn by a Mrs Rolland, or another extant pocket that has survived with a note reminiscing periods spent together by two female friends which the gift of the pocket memorializes.11 The female sociable networks evidenced in such pockets had little to do with fashionability or luxury, instead they manifest how these personal objects could serve to cement female friendships. When hand-made by one woman and worn in close proximity to the body another, a pocket could itself be part of this female gift economy, nurturing female networks of sociability.

- 9. On gift giving and reciprocation in the early-modern period, see Natalie Zemon Davis, The Gift in Sixteenth-Century France (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) and Felicity Heal, The Power of Gifts: Gift Exchange in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

- 10. Cited in Alice Morse Earle, Two Centuries of Costume in America 1620-1820 (Rutland: Charles E. Tuttle, 1971), vol. II, p. 589.

- 11. Pocket, Acc. No. MS. H.RHB.11, National Museum of Scotland. The other pocket, embroidered with wild strawberries and pansies, dated c. 1810, is in a private collection.

A small pocket made by a woman named Margaret Deas offers poignant expression of the role of these gendered objects in fostering female connexions. Margaret Deas was an inmate in a Glasgow prison in 1851 and the pocket was made as a gift to the governor’s wife.12 The motto ‘forget me not’ and her name, embroidered in her own hair on the face of the pocket are powerful reminders that destitute women with limited resources also used the pocket to form strong bonds of friendship that could overcome class difference. Too small to be functional as an actual pocket, the gift – and its survival — testify to a shared language of care and attachment between donor and recipient expressed in the shape of a pocket.

- 12. This pocket is in a private collection.

As material manifestations of specifically female forms of sociability, these various extant pockets also remind us of what we stand to gain by moving beyond the traditional written archives. Unlike Dorothy Wordsworth or Arabella Furnese who left papers in the archive, Margaret Deas has left no will, letters, diaries or account books behind. In the absence of such sources, looking at objects themselves sometimes enables historians to expand their gaze to embrace the plebeian and not just the elite. In turn, this material approach to sociability illuminates practices that cut across social divides in which pockets offered women a shared territory and language to establish links and connections. This points to a mode of sociability that had less to do with the habermasian public sphere than with an intimate yet collective female experience.

Share

Further Reading

Burman, Barbara, and Fennetaux, Ariane, The Pocket: A Hidden History of Women’s Lives 1660-1900 (London & New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

Fennetaux, Ariane, ‘Women’s Pockets and the Construction of Privacy in the Long Eighteenth Century’, Eighteenth-Century Fiction (vol. 20, no 3, 2008), p. 307-334.

Gerritsen, Anne, and Riello, Giorgio, Writing Material Culture History (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015).

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher, ‘Of Pens and Needles: Sources in Early American Women’s History’, The Journal of American History (vol. 77, no 1, 1990), p. 200-207.

Unsworth, Rebecca, ‘Hands Deep in History: Pockets in Men and Women’s Dress in Western Europe’, Costume (vol. 51, no 2, 2017), p. 148-170.