Abstract

The study of footwear contributes to our understanding of sociability in the eighteenth century in several respects. Shoes were an important part of the dress ensemble for both men and women, so changing styles can highlight shifts in eighteenth-century fashions. Shoes also affected bodily posture and movement, so related to the activities of elite society. The fashion for high heels gave elite men a commanding posture over their social inferiors, whereas dancing shoes had a supple construction that facilitated the nimble footwork required at balls. Footwear therefore helps us to understand the physical aspect of social interactions.

The shoe is a very good example of a material object that informed the practice of sociability in the eighteenth century. It had both an essential practical function and a decorative one, and informed social interactions in both respects. We will here consider the shoe as a worn material artefact that had a close relationship with the body, and which had an important role to play in social and gender relations.

Shoes are items of dress, so they have a visual importance in terms of fashion. Much historical work on shoes is from the perspective of dress history, charting how styles changed over time. Indeed, shoes were central to the dress ensemble for both men and women in the eighteenth century. Patrician men wore heeled, buckled shoes with stockings and breeches, as part of the ‘three piece suit’ that came to be regarded as the uniform of the English gentleman.1 Women too wore heeled, buckled shoes for much of the century as part of their dress ensemble. Changes to shoe styles should be regarded as part of changes to the clothing fashions of which they were a part.

- 1. David Kuchta, The Three Piece Suit and Modern Masculinity: England, 1550-1850 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

The importance of shoes, however, goes much deeper than the visual. Shoes support the whole weight of the body, so have an impact upon how that body stands and moves. Footwear design is a compromise between the agility of the naked foot and the restrictiveness of protective coverings, alongside other considerations such as cost and aesthetics. How all those considerations are weighed up depends on the needs of the wearer, since the way that shoes are made enables people to perform certain tasks, or prevents them from doing others. Shoes therefore relate quite directly to the role that the wearer is expected to take in society, including occupation, social status or gender role.

This was certainly the case in the eighteenth century. Working people wore utilitarian shoes that enabled them to carry out their daily tasks. Most men’s shoes were constructed of thick black cowhide, with hardwearing leather soles and uppers, or sometimes soles of wood. Shoes were expensive, so needed to last as long as possible: plebeian footwear often had hobnails or metal heelplates to stop them wearing out and to grip better on mud. The construction was broad, often with a squared toe. This was practical, since shoes were straight lasted in this period – meaning that lefts and rights were identical – and a broad toe enabled them to be worn without constraining the foot. While plebeian footwear was not unaffected by fashion trends, to be ‘square toed’ was to be unfashionable when the elite favoured narrower and more pointed designs.2

- 2. June Swann, Shoes (London: Batsford, 1982), p. 26.

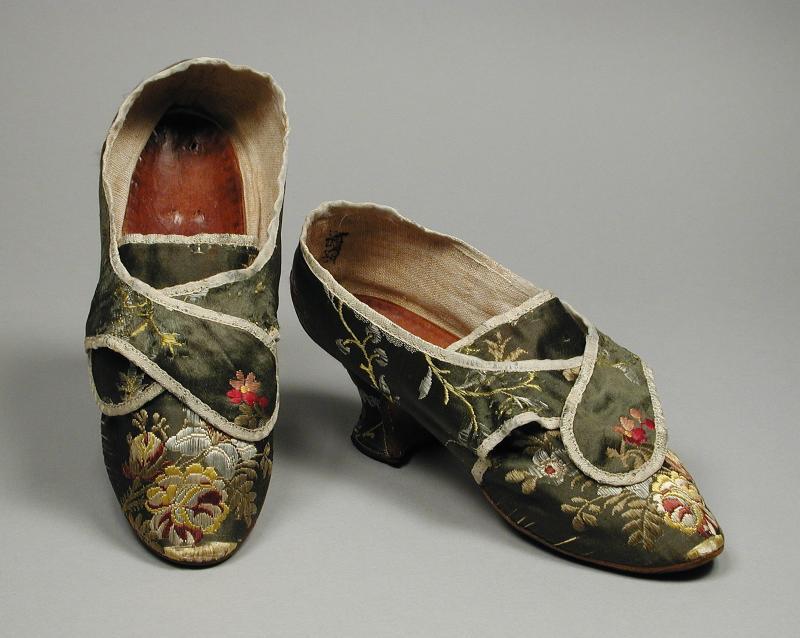

The changing design of fashionable footwear tells us a great deal about the divergence of gender roles over the course of the eighteenth century. In the early eighteenth century, elite footwear for men and women was visually similar. Both had a buckle, both could be covered in patterned fabrics, and both had a heel: although women’s heels tended to be carved from wood, and men’s were of stacked leather, they looked comparable. They were primarily suited for indoor wear, and when venturing out might be worn with pattens, wooden overshoes that kept fine footwear out of the dirt.

Some men continued to wear elaborate footwear, favouring the high heel to give them a commanding height and a polite posture. The red heel was first popularised by Louis XIV and was often the choice of fashionable Englishmen. Caricatures of ‘macaronis’ from the 1780s, however, suggested that this fashion was the target of moral criticism, associating it with foreignness and effeminacy. Increasingly, men’s shoes were plain in design, generally black in colour and with a low heel. The only decoration was provided by the buckle, which could be ornate in design and covered with sparkling jewels.

Men’s fashion underwent a revolution in the 1790s, against the backdrop of the French Revolution. The ensemble of buckled shoes, stockings and breeches came to be associated with the sins of the aristocracy, and men increasingly wore trousers or pantaloons with laced shoes or boots instead. This more military and democratic style befitted a time of war and revolution. As Hampton Weekes wrote in London in 1802, ‘Black coat, & waistcoat with Pantaloons & Hessian Boots […] is the wear of almost all the young Men here’.3

- 3. Hampton Weekes to Richard Weekes, 19 December 1802, in John Ford (ed.), A Medical Student at St Thomas’s Hospital, 1801-1802 (London: Wellcome, 1987), p. 244.

Much has been written about the ‘renunciation’ in men’s fashion at this time, suggesting that the rejection of sartorial display constituted a revolution in masculinities.4 But it is important to emphasise that these new fashions underlined the common identity of patrician men, and their claim to dominate the public sphere. The expensive, figure-hugging wellington boot emphasised the shapeliness of the leg and the physical prowess of the wearer.5 It gave the elite a refined gait, as distinct from the noisy, cumbersome tread of working men in heavy, hobnailed shoes.

Over the same period, the styles of women’s footwear diverged from those of men. If male footwear became more practical and more suited to outdoor activities, women’s became more impractical and flimsy. By the 1800s, it was fashionable for women to wear lightweight slip-on shoes, similar to modern ballet pumps. These would typically have fabric uppers made from silk or wool, with thin leather soles. They wore out so quickly that women would buy several pairs at once. This style of footwear suggested that women’s roles were domestic, in contrast with men’s that befitted the rigours of the public sphere. Shoe fashions are therefore part of the wider story of diverging gender roles over the course of the Georgian period.

When men attended a ball, they too wore lightweight, flexible shoes. It is telling that men changed into these in order to participate in an apparently frivolous activity, whereas women wore them all the time. At balls or at court, men continued to wear the old patrician ensemble of shoes, stockings and breeches. Indeed, such spaces had strict dress codes that forbade outdoor wear. Bath’s New Assembly Rooms insisted that ‘no gentleman in boots or half-boots be admitted into any of these rooms on ball nights’.6

- 6. John Feltham, A Guide to the Watering and Sea-Bathing Places (London: Longman, 1806), p. 33.

The construction of a dancing shoe was very different to that of a shoe made for walking, or a boot made for riding. Although men’s dancing shoes were typically made of leather, the uppers were much softer than the leather used for outdoor shoes. The sole too was much thinner and more flexible than the usual hard leather, with barely any heel at all. This allowed the foot to be very flexible, which it needed to be since Georgian dancing styles often involved bouncing on the toe. The dancing shoe therefore facilitated the refined motions of the polite body.

As such, it is vital to think about shoes as embodied objects. Shoes should not be studied or displayed in isolation, since they were fundamentally worn objects that had a very close relationship with the bodies that wore them. Shoes influenced the motions and postures of the wearers, as well as their visual appearance, so were an important factor in social interactions. Footwear therefore gives us an insight into the physical and material nature of eighteenth-century sociability.

Share

Further Reading

Alexander, Kimberley, Treasures Afoot: Shoe Stories from the Georgian Era (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018).

Breward, Christopher, The Culture of Fashion (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995).

Davidson, Hilary, Dress in the Age of Jane Austen (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

McCormack, Matthew, ‘Wooden shoes and wellington boots: the politics of footwear in Georgian Britain’, in Christopher Fletcher (ed.), Everyday Political Objects (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021), p. 104-119.

Riello, Giorgio, A Foot in the Past: Consumers, Producers and Footwear in the Long Eighteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

Semmelhack, Elizabeth, Shoes: The Meaning of Style (London: Bloomsbury, 2019).