Résumé

During the long eighteenth century, a huge wave of exotic mania led to various social interactions characterised by the refinement of manners and the love of luxury. The term ‘exotic’ was associated with unfamiliar flora and fauna as well as with rare objects exhibited in places of sociability such as gardens, public and private menageries, museums, salons, tea-rooms, theatres, opera houses and many others. If it is true that North America, the Bahamas, Canary Islands, the Indian Ocean islands of Mauritius and Madagascar represented the ideal destinations for explorers in search of natural history discoveries, then it is equally true that the Orient attracted the interest of collectors resulting in the exotic modes of chinoiserie and turquerie.

During the long eighteenth century, a wave of exotic mania swept England so fully that the passion for the exotic led to various social interactions characterised by the refinement of manners and the love of luxury. The term ‘exotic’ - which must not be misunderstood with exoticism, a term coined in the nineteenth century standing for the sense of nostalgia experienced by the beholder of a far away country1 - was associated with unfamiliar flora and fauna as well as with rare objects exhibited in such places of sociability as gardens, public and private menageries, museums, salons, tea-rooms, theatres, opera houses and so forth. Across Europe and in particular in such a polished and commercial nation as England, the purchase of exotic items appears to be a form of luxury defined by Adam Ferguson as ‘a manner of life which we think necessary to civilization, and even to happiness. It is [...] the parent of arts, the support of commerce, and the minister of national greatness, and of opulence’.2 The exotic, which first emerged in the seventeenth century, reached its maximum expression in the eighteenth century when the establishment of trade routes continued on a larger scale to supply Europe with a great variety of exotic goods (including china, silk, perfumes, and precious stones), giving lustre to those members of society whose aim was to exhibit social and political status, as well as international reputation.

Exotic gardens as sites of sociability

Members of the nobility and the royal family were interested in exotic plants notably from the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and China, which were brought back by plant collectors such as John Ellis (1710-1776), and David Douglas (1799-1834). In particular, Princess Augusta, the Princess of Wales and daughter-in-law to King George II, started a collection of exotic living plants and trees at Kew in 1759 which distinguished itself for its specimens collected by Captain Cook. Originally developed to display a growing collection of non-exotic and exotic plants (see for example Camellia Sinensis, Coffea Arabica, Theobroma Cacao, Saccharum Officinarum and Cinchona Officinalis), botanic gardens promoted a recreational message of social inclusiveness leading to a deep transformation of social habits, social curiosity and social interests in Great Britain and all over Europe. As aptly summarised by S. Easterby-Smith, ‘[t]he gardens functioned as sites of sociability, where amateurs of botany could meet and converse with each other and with professional gardeners about topics of interest. They were locations in which the exchange of objects and of information, which was so fundamental to the development of knowledge, could take place’.3 As a paramount example of exoticism, the royal gardens at Kew were also characterised by an extraordinary collection of ornamental buildings among which the Great Pagoda (1762), designed by Sir William Chambers (1723-1796) - the most accurate reconstruction of a Chinese building in Europe at the time - along with a Moorish Alhambra and a Turkish Mosque. A popular folly of the age, which stood at a towering ten storeys (163 feet)4 and was decorated with 80 dragons, the Pagoda was tremendously fashionable stirring the interest of notable historians, politicians, traders and men of letters.

- 3. Sarah Easterby-Smith, ‘Botanical Collecting in Eighteenth-Century London’, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine (vol. 34, no. 4, 2017), p. 279-297.

- 4. On the excessive height of the Pagoda, Horace Walpole commented ‘we begin to perceive the Tower of Kew from Montpellier Row; in a fortnight you will see it in Yorkshire’. Horace Walpole, letter to Earl of Strafford, July 5, 1761, in The Letters of Horace Walpole, Earl of Orford, ed. Peter Cunningham (London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1891), vol. 3, p. 410.

Exotic animals as symbols of social status

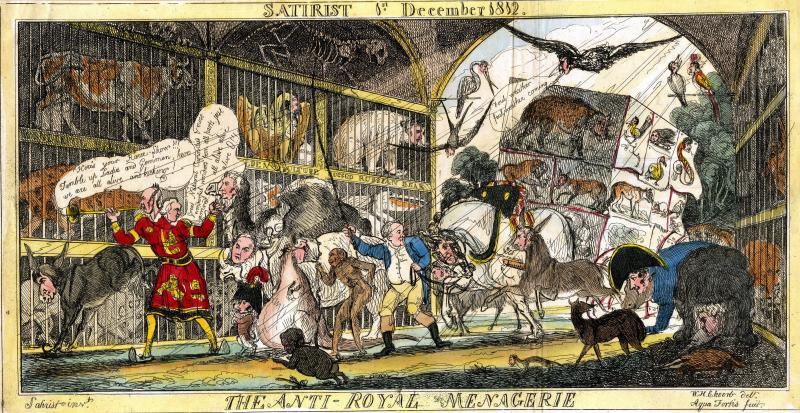

Such a crave for exoticism was also expressed by an excessively intense enthusiasm for exotic animals (lions, elephants, monkeys, crocodiles, kangaroo, turtles and so forth) which were exhibited at Georgian menageries (public or private) as objects of fascination and wonder whose aim was to entertain guests and satisfy their curiosity for the animal world. The privileged gentry, the aristocracy, the fashionable and rich metropolitan elite, as well as men of letters sought to create their own private menageries as places of collective interaction. Exotic birds, antelopes, lions, monkeys and porcupines were exhibited at Joshua Brookes’s menagerie at the end of Tottenham Court Road. Between 1757 and 1758, Georgian Londoners could go to the Talbot Inn on the Strand in order to behold Mr Richard Heppanstall’s collection of camels. Living kangaroos became part of Queen Charlotte’s collection at Kew from 1792 and a parade of elephants, tigers, bears, rhinoceroses and vultures could be seen at Gilbert Pidcock’s menagerie at Exeter Exchange. There were also private menageries owned by the Duchess of Portland, the Earl of Shelburne, the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham, Sir Robert Walpole, Sir Hans Sloane and many others. As expressed by Christopher Plumb:

[…] exotic animals and birds [...] increasingly became part of London life in the eighteenth century. They were sold in the premises of bird sellers and animal merchants, and placed on display in taverns or menageries. Foreign birds and beasts occupied not only the places where Londoners lived, worked and visited but also their minds; in Georgian cultural life the ways in which these birds and animals were written or spoken about expressed a wide range of cultural attitudes or concerns.5

From this perspective, exotic animals were seen as living commodities to be entertained by and to consume. For example, bear grease, civet and turtle were considered to be highly desirable ingredients: wigs, hallmarks of gentility and respectability, were rendered stylishly appealing with the use of a pomade made of bear grease; civet-scented fragrances were considered symbols of Georgian luxury and decadence and, last but not least, the turtle soup was an elite delicacy standing for the social status of the ruling classes who owned colonial plantations in the Caribbean. Notably, collective turtle consumption was considered to be a sociable affair entailing polite enjoyment of exotic food. This luxury good became an emblem of gentility, sobriety, fellowship and sociable relations to such an extent that, as attested by the dinner register of the Royal Society’s dining club, a gentleman who wished to be accepted as an Honorary Member of the aforementioned club was supposed to donate a turtle in order to signify his status and generosity (Plumb 71).

In line with Joseph Addison and Steele’s conversational model aimed at promoting an ideal of polite sociability, the exotic appears to be a topic of good-humoured conversation which reflected and shaped broader economic and political debates. In his famous essay on the Royal Exchange in the Spectator n° 69, dated 19 May 1711, Addison describes the fictional Mr Spectator’s delight in mixing with Oriental merchants (Armenians, Jews, and so forth) emphasising the interconnections between exotic commodities from the remotest corners of the Earth:

- 5. Christopher Plumb, The Georgian Menagerie. Exotic Animals in Eighteenth-Century London (London and New York : I.B. Tauris, 2015), p. 6.

The Food often grows in one Country, and the Sauce in another. [...] The Infusion of a China Plant sweetened with the Pith of an Indian Cane. [...] The single Dress of a Woman of Quality is often the Product of a hundred Climates. The Muff and the Fan come together from the different Ends of the Earth.6

From Addison’s words it is clear that the benefits of commerce can be found in the great variety of commodities, both convenient and ornamental, which are imported from exotic countries. As a prime instrument of England’s imperial agenda, the commerce in exotic foodstuffs played a significant role in paving the way for globalization in the early modern period.

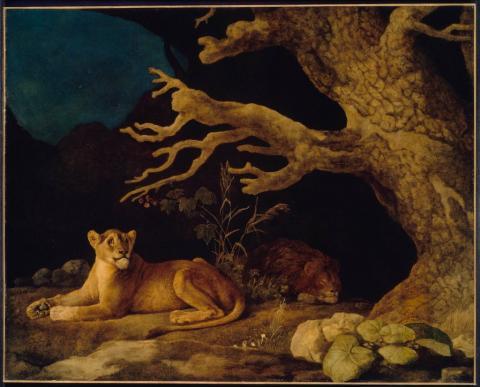

By praising the great advantages of a trading nation, Addison also mentions the multitude of animals lurking beneath seas and hidden in deserts that the natural historian should observe according to the Enlightenment search for knowledge. Anecdotes of exotic animals are reported by Addison who, in order to show what are the entertainments of the ‘Politer Part of Great Britain’, narrates the famous Neapolitan soprano, Cavalier Nicolino Grimaldi, playing the role of the protagonist in the opera of Hydaspes, thrown naked into an amphitheatre to be devoured by a lion (Spectator n° 13, 15 March 1711). It is highly significant that this story of amusement for which Addison started an investigation on the real savagery of the animal, focuses on such a wild beast as the lion which is notably the emblem of the English nation. The Georgians were fascinated by animals that savaged human beings whose anecdotes circulated prolifically in the press and in elite circles. The dangers of exotic animals, as well as their exhibition and even their dissection attracted the audiences for museums and menageries drawing together a network of naturalists, conversationalists and intellectuals. At the very beginning of the eighteenth century, the first person in Britain to be killed by a tiger in an exhibition of wild beasts at the White Lion Inn was Hannah Twynnoy, a 34-year-old working as a maid in a town called Malmesbury.7 In the 1760s, there were stories of a panther named Lucy at the Tower of London menagerie which became notorious for having torn off in a terrible way the arm a woman. Likewise in the 1820s, Wallace the lion, touring with Wonbwell’s Menagerie, tore the limbs off three people and killed a man after escaping in Derbyshire. But apart from these macabre stories circulating among ordinary Londoners and privileged gentry and aristocracy, conversations about exotic animals took place in drawing rooms, salons, royal palaces, and menageries.8 In such places of sociability, visitors, guests and spectators could expect to take afternoon tea while watching and conversing about living or dead animals.

- 6. Joseph Addison, The Spectator (no. 69, 19 May 1711).

- 7. Her gravestone epitaph appears to be a memorial poem alluding to her tragic death: ‘In bloom of Life / She’s snatchd from hence, She had not room / To make defence; / For Tyger fierce / Took Life away. / And here she lies / In a bed of Clay, / Until the Resurrection Day.’

- 8. See for example the salon of collector Sophia Banks (1744-1818) at 32 Soho Square, the menagerie of the Duke of Richmond at Goodwood, and Anne Hunter’s (1742-1821) anatomical museum.

The exotic mode of Chinoiserie fostering politeness

Another eighteenth-century exotic mania forging social relationships is the taste for chinoiserie porcelain, one of the artistic manifestations of Le Rêve chinois, which reached its height thanks to the feminine and domestic culture of tea drinking. Chinoiserie was a style inspired by art and design from China, Japan and other Asian countries in the eighteenth century. As a signifier of sophisticated taste, chinoiserie was a fundamental part of polite society in which aristocratic and socially important women used to collect a great variety of Chinese decorative objects. Queen Mary, Queen Anne, Henrietta Howard, the Duchess of Queensbury, the second Duchess of Portland, and the Countess of Ilchester are the best known collectors of porcelain and other chinoiserie which were essential to create appropriate settings for the ritual of tea drinking. Literary and non-literary depictions of chinoiserie can be found in Alexander Pope's Rape of the Lock (1717), Daniel Defoe’s Captain Singleton (1720), Jonas Hanway’s Essay on Tea (1756), Oliver Goldsmith’s Citizen of the World (1762) and William Chambers’s Dissertations on Oriental Gardening (1772).

Apart from their need to attest their purchasing power and their prominent role in increasing the fashionable Oriental vogue, elite Georgian purchasers seemed, paraphrasing John Locke, to furnish their minds with ideas about China’s art and language. Elite women and their obsession with chinoiserie seem to project Locke’s conceptual metaphor - ‘the mind is an empty cabinet to be furnished’ - in order to attain several truths. One of these truths was that with their collecting of Chinese and Chinese-inspired objects and art, wealthy and refined women were contributing to the socio-cultural exchanges between East and West, between Oriental and European cultures of sociability.

By combining European rituals of politeness with Chinese teaware, upper-class women were able to activate a change of taste in the circle of their acquaintance. Such an integration of exoticism into domestic forms of sociability can be explained with David Hume’s theory of taste according to which those ‘who can enlarge their view to contemplate distant nations and remote ages’9 will pronounce positively on those cultures labelled as ‘barbarous’ departing widely from the European taste. In this encounter between East and West, mixing up categories of sociability, refinement of taste is achieved by what Hume calls the ‘interposition’ of ideas, the interposition of cultures.

- 9. David Hume, Four Dissertations (London: A. Miller, 1757), p. 203.

Eighteenth-Century Turquerie as an orientalizing and freeing phenomenon

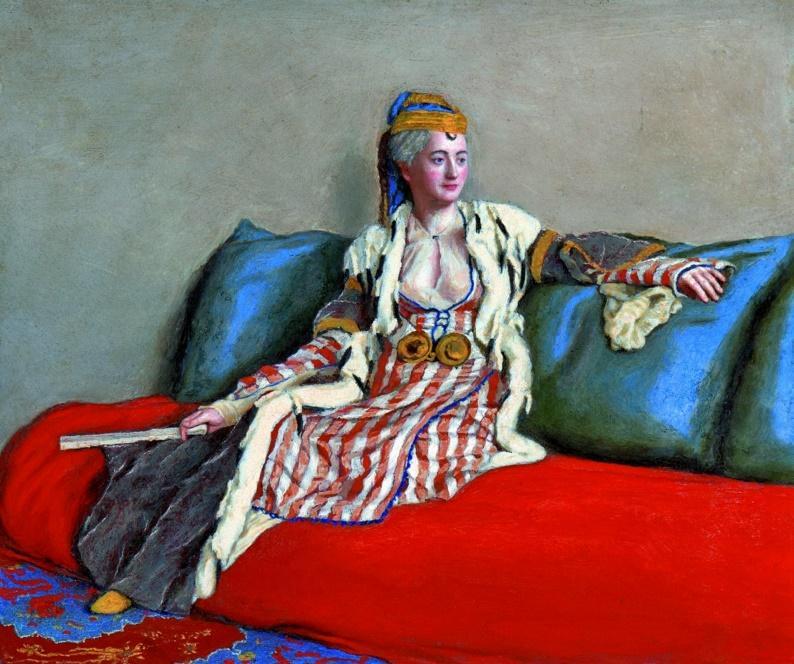

A most fashionable exotic mania was turquerie, a commercial and artistic phenomenon aimed at orientalizing European civility. Like chinoiserie, which was mainly considered as a decorative and architectural style creating new spaces of socialiblity, turquerie deeply influenced different social spaces and practices. With the arrival of Ottoman embassies at the courts of Europe, the lure of the Turkish style was attracting members from royalty and aristocracy who used to attend the theatre to see a play or opera with Turkish atmospheres. In their domestic spaces, they loved to wear Turkish costumes while smoking Turkish tobacco and reading Oriental tales featuring Eastern emperors, tsars or sultans as envisioned in the Arabian Nights. From this perspective, turquerie provided new Oriental modes to express one’s social position. In particular, Turkish dresses (flowing gowns belted with ornate bands; ermine-trimmed robes; taseled turbans) and decorations (strings of pearls) were particularly appealing for aristocratic women who were often depicted wearing their exotic clothing. A case in point is the portrait of Lady Montagu in Turkish dress (1756) by Jean-Étienne Liotard attesting the lure of turquerie invoking the East to refashion the domestic. In particular Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762), mother, thinker, and author of The Embassy Letters (1762), described Turkish fashion and life inside a harem and her narrative deeply influenced the way Europeans envisioned the Ottomans and their rituals of sociability. Her letters circulated among her social circle stimulating a broad admiration for Ottoman behaviours and goods. The success of turquerie was mainly due to its liberating function, according to which British men and women could dress alla turca fulfilling their hedonistic desires thereby exploring social ways of being. But the most sociable import from the Ottoman Empire, supplier of luxury goods such as spices, perfumes, coffee and tea, was the coffeehouse,10 the centre of urban sociability fostering dialogue and human relationships without the restrictions of family, society and the state. According to Habermas, the coffeehouse represents a medium for the formation of bourgeois public opinion.11 The shared practice of drinking an Oriental hot beverage in an exclusively male-dominated space with the aim of sharing opinions, ideas and news appears to be the most highly social phenomenon of the Enlightenment. By melting private individuals and public debates, the coffeehouse was a blended space mixing up properties and categories of eighteenth-century sociability.

The lure of the exotic in the Enlightenment resulted in a hybridizing phenomenon incorporating the otherness of far away countries into practices and sites of sociability. The many ways in which the Georgians exoticised their concepts of sociability are indicative of how intriguing the encounter between British culture and the exotic was, thereby creating new forms of social interactions which still play an essential role in contemporary society.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Alayrac-Fielding, Vanessa, La Chine dans l’Angleterre des Lumières (Paris: PUPS, 2016).

Alayrac-Fielding, Vanessa (ed.), Rêver la Chine: chinoiseries et regards croisés entre la Chine et l’Europe (Lille: Invenit , 2017).

Avcioglu, Nebahat, Turquerie and the Politics of Representation (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2011).

Chambers, William, Dissertations On Oriental Gardening (London: W. Griffin, 1772).

Grigson, Caroline, Menagerie: The History of Exotic Animals in England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

Montagu, Mary Wortley, Letters Written During Her Travels in Europe, Asia and Africa (London: T. Becket and P.A. De Hondt 1763).

Porter, David, The Chinese Taste in Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Rousseau, G. George Sebastian and Roy S. Porter (eds.), Exoticism in the Enlightenment (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990).

Sloboda, Stacey, Chinoiserie: Commerce and Critical Ornament (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014).

Williams, Haydn, Turquerie. An Eighteenth-Century European Fantasy (London: Thames & Hudson 2014).

In the DIGIT.EN.S Anthology

Daniel Defoe, The Fortunate Mistress [Roxana] (1724), p. 210-216.

David Hume, Of the Standard of Taste (1757).