Abstract

As a bluestocking hostess, Frances Boscawen (1719-1805) is often mentioned in connection with Elizabeth Montagu or Elizabeth Vesey, but so far, little scholarly attention has been paid to Boscawen’s sociable activities. As the wife of an admiral, Boscawen began as a political hostess, doing the honours at her marital home, 14 South Audley Street. Her parties are thus likely to have entertained a different crowd: elite fashionability and political clout were more important than literature or the arts. After having been widowed, however, Frances Boscawen strengthened her bluestocking connections, entertaining in London as well as in the country.

Keywords

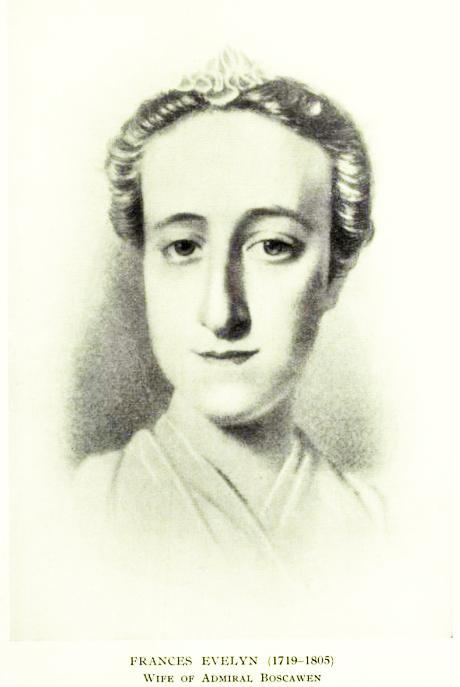

Born in 1719, Frances Evelyn Glanville was a distant relative of diarist John Evelyn, and – via her mother, also called Frances Glanville, who died shortly after her birth – entitled to a considerable inheritance on her marriage.1 In 1742, she married the younger son of Hugh Boscawen, Viscount Falmouth, Captain Edward Boscawen (1711-1761), who had begun a promising career in the navy and became a Member of Parliament that year. Throughout their marriage, Edward Boscawen’s naval successes – he was promoted to rear-admiral in 1747 – also meant that he was frequently absent for months or even years, taking part in various dangerous battles during the Seven Years’ War.2 As a young wife, and quickly also a young mother, Frances Boscawen suffered bitterly when parted from her husband, but his career, and his absences, forced her to exert herself socially. She regulated home affairs on her own, and the house she bought and renovated in her husband’s absence, 14 South Audley Street, would be the location for her London-based assemblies for the rest of her life.

As an admiral’s wife, she could not possibly have kept out of political sociability. Her house was frequently filled with family members and navy acquaintances for dinners and assemblies, and thus provided opportunities for Boscawen to exert a form of social politics in the manner described by Elaine Chalus:

- 1. Admiral’s Wife: Being the Life and Letters of The Hon. Mrs. Edward Boscawen from 1719-1761, ed. Cecil Aspinall-Oglander (London, New York, Toronto: Longmans, Grenn and Co. 1940), p. 15.

- 2. He also served on the Board of Admiralty and became a member of the Privy Council in 1758. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Boscawen (accessed 2 November 2022).

By no means all of the socializing that took place in the home was intimate mixing among friends. While hosting public days was one of the socio-political duties of the summer for women from politically active aristocratic families, fashionable women in London often opened their homes on designated days or evenings during the parliamentary season.3

- 3. Elaine Chalus, ‘Elite Women, Social Politics, and the Political World of Late Eighteenth-Century England’, The Historical Journal (n° 43, vol. 3, 2000), p. 669-697, here p. 684.

Boscawen’s dinner parties served to gather news and promote her husband’s career by means of diligent networking. Her sociable duties would have included close attention to interior decoration, as personal taste was necessary to impress visitors. Thus, Boscawen informed her husband: ‘Taste I always pretended to and must own I shall be greatly disappointed if you do not approve that which I have displayed in Audley Street’ (Aspinall-Oglander, I, 129). To be polite, the letter continues, she had invited his brother as well as a member of Parliament, Sir Charles Frederick, and his wife to dinner. Even then, she seems to have preferred small sociable circles and dinner parties. Yet in the 1750s, while her husband served on the Board of Admiralty, her ‘drums’,4 as she called them, became more elaborate, and the question who to ask a more delicate affair. In another letter to her husband, she outlined a party to which she had not dared invite his superior, Admiral Lord Anson, ‘fearful that I could not get a guineas-table’. To her great satisfaction, she later heard that her assembly was praised in the highest terms by a lady who had attended it: ‘so much politeness, accompanied with so much ease, she had never observed in anybody. In short, that I did the honours in a certain way that was agreeable and attentive to everybody, and yet (seemingly) with great ease to myself’ (Aspinall-Oglander, I, 166). Organizing the event had been a matter of some concern rather than great ease, but Boscawen evidently had notable success as a hostess, and reference to her agreeable politeness and elegant conversation abound in later references to her among the bluestocking circles, too.5

Comparing her own talents as a political wife to that of other ladies of her acquaintance, Boscawen felt a sense of achievement, dutifully couched in submissive terms in letters to her husband:

I cannot help flattering myself that you think your choice of a wife happy in that point – in your public character. [...] I cannot but reflect with indignation how much ‘tis in a woman’s power to distress a brave or learned man amongst his own society and friends, at his table and round his domestic hearth, from whence a man should draw the best sources of social felicity’ (Aspinall-Oglander, I, 206).

Maintaining a public character had its price: she had spent as little as she could, she told her husband, ‘consistent (I must add) with your gloire, for I have kept a very good house, and I have had abundance of people in it’ (Aspinall-Oglander, I, 214).

- 4. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a drum was ‘A social gathering held at a private house, attended by people from fashionable society’ (www.oed.com, s.v. ‘drum, n° 3’).

- 5. See, for instance, Boswell, Life of Johnson, ed. R. W. Chapman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970): ‘her conversation the best, of any lady with whom I ever had the happiness to be acquainted’, p. 978; Frances Burney, The Journals and Letters of Frances Burney (Madame D’Arblay), ed. Joyce Hemlow, 12 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), IV, p. 107.

Like other members of the bluestocking circle, Frances Boscawen was proud to consider herself a dutiful, loving wife to her husband, a loyal subject and a patriot to her country, and remained conscious of social distinctions. Boscawen’s first biographer, Aspinall-Oglander, downplayed her interest in politics, but as Elaine Chalus reminds us, ‘the best hostesses [...] were charming, good at handling people, sensitive to social nuance, and possessed a thorough understanding of the workings of the political world’ (Chalus 689). Indeed, Boscawen’s surviving letters prove that she was knowledgeable about contemporary politics, frequently supplying her husband with details in her journal-letters, and that she remained interested especially in naval politics for the rest of her life.6 As was usual for ladies of her social status, she also travelled to Bath or Tunbridge Wells to drink the waters and enjoy the easy-going sociability of these watering places. She became acquainted with Elizabeth Montagu at Tunbridge Wells in 1750, where, Montagu told her husband, they often passed the evening together, ‘partly in conversation, partly in reading.’7

- 6. See, for instance, Admiral’s Widow: Being the life and letters of The Hon. Mrs. Edward Boscawen from 1761 to 1805, ed. Cecil Aspinall-Oglander (London, New York, Toronto: Longmans, Grenn and Co. 1942), ch. XVI, for her interest in, and disapproval of, the American War.

- 7. Elizabeth Montagu, the Queen of the Bluestockings: Her Correspondence from 1720 to 1761, ed Emily Climenson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, [1906] 2011), vol. I, p. 277; see also https://emco.swansea.ac.uk/emco/person/38/.

After the death of her husband in 1761, Boscawen seems to have turned increasingly to her bluestocking friends and ‘rational’ entertainments, favouring conversation over cards. His will had left her a prosperous widow, and she continued to keep a hospitable dinner table (Climenson, I, 230). Indeed, Elizabeth Eger suggests that ‘her long widowhood formed the most sociable period of her life. She returned to her old London house at 14 South Audley Street, where she now hosted popular bluestocking assemblies; her guests included Elizabeth Montagu, Dr Johnson, James Boswell, Joshua and Frances Reynolds, Elizabeth Carter, and later, Hannah More.’8 Hester Thrale also belonged to her circles. In 1778, Thrale remembers a ‘Talk one Evening at Mrs Montagu’s of the present State of Politicks’, an anecdote which immediately leads her on to ‘Another Night – at Mrs Boscawen’s’ where recent sermons at everyone’s preferred churches were discussed, and Lord Chatham’s political courage as well as Samuel Foote’s wit came under scrutiny.9 Hannah More not only kept up a lively correspondence with Mrs Boscawen, but also described Boscawen’s parties in her letters to others. Thus, in 1775, she mentions a ‘smaller party’ at Mrs Boscawen’s, initiated after a brilliant assembly at Mrs Montagu’s, where so many famous wits were together ‘that so many suns could not possibly shine at one time’, and Boscawen and More agreed that ‘from fewer luminaries, there may emanate a clearer, steadier, and more beneficial light’.10 More describes conversaziones at Mrs Boscawen’s, where she met Lord Howe, freshly returned from America, and even a party her friend was kind enough to give for her, to which Soame Jenyns and Richard Owen Cambridge were invited, as well as ‘a few sensible ladies’ (Roberts, I, 70, 159). South Audley Street also hosted larger assemblies, for instance an enjoyable evening of ‘above forty people, most of them of the first quality’, according to More, who described her hostess much as the unknown lady who praised her drum had done: Boscawen was ‘herself, easy, well-bred, and in every place at once; and so attentive to every individual, that I dare say everybody, when they got home, thought as I did, that they alone had been the immediate object of her attention’ (Roberts, I, 93).

- 8. Elizabeth Eger, ‘Boscawen, Frances Evelyn (1719–1805)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/47078 (accessed 1 November 2022).

- 9. Hester Thrale, Thraliana: The Diary of Mrs. Hester Lynch Thrale 1776-1809, ed. Katharine C. Balderston, 2 vols (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 2nd ed. 1951), vol. 1, p. 235.

- 10. Memoirs of the Life and Correspondence of Mrs. Hannah More, ed. William Roberts (London: Seeley and Burnside, 3rd ed. 1835), vol. 1, p. 53-54.

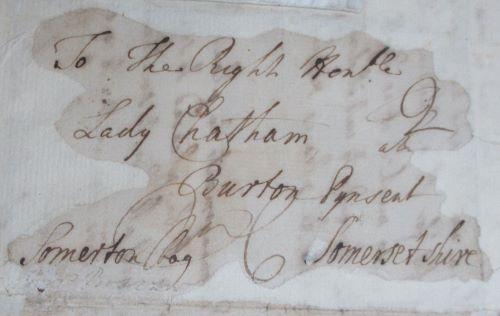

Boscawen moreover continued to make good use of her political networks, both to help her acquaintances rise in a system that still relied on political connections, and to further the career of her sons and later grandsons. Thus she (unsuccessfully) tried to get Dr Charles Burney appointed as organist in the Queen’s Band in 1782 and collected subscriptions for Frances Burney’s novel Camilla in 1796.11 Four volumes of Boscawen’s letters to Hester Pitt, Lady Chatham, a life-long friend, are held at the National Archives among the Chatham papers, spanning the decades between 1748 and 1801.12

In one of her letters to Lady Chatham, she wrote about her youngest son to ask her to talk to her husband about making him Auditor of the Dutchy of Cornwall: ‘my constant Desire to serve my Son will not suffer me to omit an Opportunity [...] Mr Boscawen’s Claims are his Father’s Merits, & his only Dependence Lord Chatham’s Friendship’.13 Despite differences in their political loyalties, Boscawen regularly cajoled her more reclusive friend to see her in London, chatting about the operas, plays, assemblies, masquerades and balls she herself attended. London was not the only location for her hospitality: There are many references to, and by, individual members of the bluestocking circles visiting Boscawen in her country residences, first Hatchlands Park, sold in 1769, then rented ‘cottages’ at Enfield and Colney Hatch, both playfully called Glan Villa in a pun on her maiden name, and finally Rosedale at Richmond. Boscawen also spent a lot of time visiting friends such as Mary Delany and the Duchess of Portland at Bulstrode, and, in later life, her married children at Badminton and Bill Hill.14

Not having left any literary publications of her own, Frances Boscawen has so far attracted little scholarly attention. However, in her own day, her letters were compared to those of Elizabeth Montagu and Mme de Sévigné, and for historians interested in sociability, they provide ample material for further research. An instance might be Boscawen’s description of the Lady’s Club that Lady Pembroke and others established at Almack’s in 1770 (Autobiography and Letters of Mary Delany, I, 261-63). She was glad her daughter, the Duchess of Beaufort, refused an invitation, expecting ‘deep and constant’ play to be the main amusement. Yet London sociability changed with the years, and Boscawen increasingly complains about the late hours of fashionable society. Lady Northampton, she wrote, ‘observes very justly that London is so alter’d since her friends us’d to be numerous & sociable, that now her Hour of rest wou’d arrive sooner than any One wd knock at her door'.15 At Badminton, the Duke of Beaufort’s elegant home, she had to play whist, she told Mary Delany, although ‘Quadrille was much better suited to my capacity; but that is out of fashion, it seems’ (Autobiography and Letters of Mary Delany, I, 478-79). Not even polite receptions were polite any more, she claimed: ‘Formerly people were accus’d of ‘being so obliging that they ne’er oblig’d’ the present Age has entirely clear’d it self of that Imputation, & takes very good care not to offend by too much Assiduity’.16

- 11. For her efforts concerning Dr Burney, see Roger Lonsdale, Dr. Charles Burney: A Literary Biography (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), p. 295 and 320.

- 12. 'Letters of Mrs Boscawen to Lady Chatham', The National Archives, Kew (PRO 30/8/21 and 30/8/22). Aspinall-Oglander does not seem to have been aware of these. A selection has been printed in So Dearly Loved, So Much Admired: Letters to Hester Pitt, Lady Chatham, from her relations and friends, 1744-1801, ed. Vere Birdwood (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1994).

- 13. PRO 30/8/22, part II, 25 Jan 27 [sic].

- 14. For her friendship with Delany, see Clarissa Campbell Orr, Mrs Delany: A Life (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2019), p. 249. Also Alain Kerhervé, Mary Delany (1700-1788): Une épistolière anglaise du XVIIIe siècle (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2004).

- 15. PRO 30/8/22, 11 May [no year].

- 16. PRO 30/8/22, 10 October [no year].

In her poem Bas Bleu, Hannah More paid tribute to Mrs Boscawen’s conversational powers (‘Each art of conversation knowing/ High-bred, elegant Boscawen’), as did Nathanial Wraxall in his Memoirs: ‘Mrs. Boscawen, though inferior in literary reputation to Mrs. Montagu, and perhaps possessed of less general information, yet conciliated more goodwill. She had an historical turn of mind, and in the course of a long life passed among the upper circles of society she had collected and retained a number of curious or interesting anecdotes of her own times.17 Hester Thrale considered her lacking in ‘Worth of Heart’ and ‘Useful knowledge’, but strong in good humour (Thraliana, I, 330). While Thrale awarded herself full points for sensibility, she did concede that Boscawen beat her in ‘Conversation Powers’ by one point: strong praise indeed from Mrs Thrale.

- 17. Nathanial Wraxall, The Historical and Posthumous Memoirs of Sir Nathaniel William Wraxall, 1171-1784, ed. Henry B. Wheatley. 5 vols (London: Bickers & Son, 1884), vol. 1, p. 112.

Boscawen’s life was not free from tragedy and loss, and her last years were embittered by the French Revolution and the ensuing wars.18 During the reign of terror, she reminisced to Lady Chatham that she had met many of those who now died under the guillotine in more sociable times:

I pass [the Heat] very quietly under the Shade of my Trees, or in cool Rooms, where I may reflect if I please how many french Ladies I entertain’d in them during the past Summers who have now suffer’d & been put to death on the Scaffold. A Duchesse de Biron, a charming Woman: a Comtesse the Bouflers, la Comtesse Emilie de Bouflers, sa belle Fille, & then a whole Family of Montboisier who liv’d there long [...] my old Friend, & next-door Neighbour Paoli is I hope triumphant after much suffering’.19

Four of her own grandsons were ‘embark’d in This cruel War […] One does not see the Way Out of It’.20 Boscawen died in 1805, long before the Napoleonic Wars ended. By then, the bluestocking social circles had come to an end, possibly because social opinion had turned against the latest generation of intellectual women – Mary Wollstonecraft and Helen Maria Williams – whose progressive ideas the bluestockings of the first generation did not share, but may nonetheless have inspired.

- 18. Boscawen’s second son William had died just when Lord Chatham had got him ‘the Commission I so much desir'd for this lovely Youth’ (PRO 30/8/21, part 1, 5 Sept 1769). The oldest died at Spa in 1774. Frances Burney considered Lord Falmouth, Boscawen’s only surviving son, dull and heavy (Journals and Letters, ed. Hemlow, vol. 1, p. 162 et 250).

- 19. PRO 30/8/21 30 July 1794.

- 20. PRO 30/8/21, 1 Oct 1794.

Share

Further Reading

Boyington, Amy, Maids, Wives and Widows: Female Architectural Patronage in Eighteenth-Century Britain (PhD Thesis in open access, 2017). Ref.: 10.17863/CAM.18372. See chapter on Frances Boscawen at Hatchlands.

Eger, Elizabeth (ed.), Bluestockings Displayed. Portraiture, Performance and Patronage, 1730-1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Eger, Elizabeth, Bluestockings: Women of Reason from Enlightenment to Romanticism (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

Franklin, Caroline, 'Enlightenment Feminism and the Bluestocking Legacy', in Devoney Looser (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Women’s Writing in the Romantic Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 115-128.

Harcstark Myers, Sylvia, The Bluestocking Circle: Women, Friendship, and the Life of the Mind in Eighteenth-Century England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990).

Heller, Deborah (ed.), Bluestockings Now! The Evolution of a Social Role (Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, 2015).

Pohl, Nicole and Betty A. Schellenberg (eds.), Reconsidering the Bluestockings (San Marino: Huntington Library and University of California Press, 2003).