Quote

"Without a play-bill, no true play-goer can be comfortable."

Links to the Encyclopedia:

Keywords

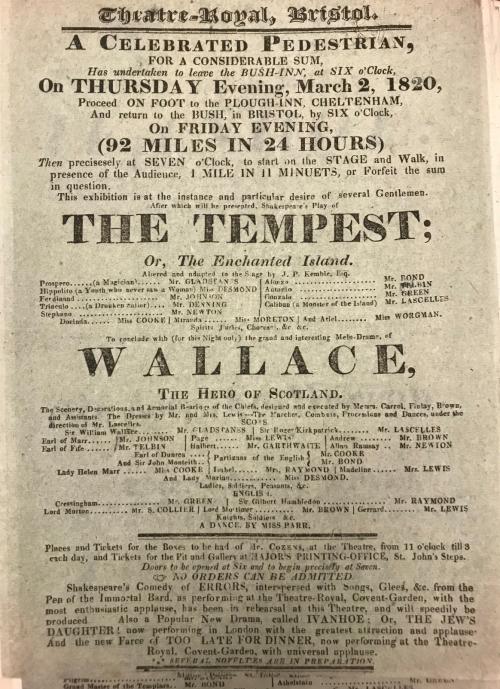

The TATLER in future will contain the Play-bills of the evening. They will be printed in an open and distinct manner, to suit all eyes ; and, it is hoped, may serve as companions to the theatre, like the regular bills that are sold at the doors. The measure has been adopted on the friendly suggestion of a Correspondent, who thinks that the public will not be sorry for this union of a paper with a play-bill ; and that by and by, to use his pleasant quotation, Tatlers will be “ frequent and full” in the pit and boxes. We shall be glad to see them. Nothing will give us greater pleasure than to find ourselves thus visibly multiplied, and to see the ladies bending over us. Happy shall we be, to be pinned to the cushions for their sakes.

Without a play-bill, no true play-goer can be comfortable. If the performers are new to him, he cannot dispense with knowing who they are: if old, there are the names of the characters to learn, and the relationships of the dramatis persone: and if he is acquainted with all this, he is not sure that there may not be something else, some new play to be announced, or some new appearance. The advertisements in the papers will not supply him with the information, for they are only abridgments: and he cannot try to be content with a look at the play-bills at the door, for then he would grudge his pence: and he that grudges his pence, cannot be a genuine play-goer. How would he relish a generous sentiment, or presume to admire a pretty face? There is a story, in the tales of chivalry, of a magic seat, which ejected with violence any knight who was not qualified to sit down in it. If the benches of the theatre could be imbued with the noble sentiments that abound on the stage, thus would they eject the man who was too stingy to purchase a play-bill.

But the above are not the only reasons for the purchase. The Tatler, for instance, will in future be sold at the play-house doors, as well as by the newsmen. They must be so, or they would not be play-bills. Now the poor people who sell the play-bills deserve all the encouragement that can be given them, for they prefer industry to beggary, and go through a great deal of bad weather and rejection. We may suppose that people who do this, do it for very good reasons. They look as if they did, for they are a care-worn race; they defy rain and mud, and persevere in trying to sell their bills with an importunity that makes the proud angry, and the good-tempered smile. If you look into the face that is pursuing at your elbow, or jogging at the window of your coach, you would often see cause to pity it. However, not to dwell upon this point, or to make a sad article of one that is intended to be merry, on every Tatler which these poor people sell, they will get a half-penny. When we consider the stress which great statesmen lay upon pence and pots of beer, in their financial measures, we hope this will not have “ a mean sound,” except in the ears of the mean passions of pride and avarice. For our parts we affect to despise nothing that represents the food and raiment of mothers and children; though we often wonder how great statesmen can lay so much stress upon the pence they dole out, and so little upon the thousands they receive. —But we shall be stopping too long at the doors.

If a play-goer has a party with him, especially ladies, the purchase of a bill gives him an opportunity of shewing how he consults their pleasure in trifles. If he is alone, it is a companion. He has also the glory of being able to lend it: —though with what face any one can borrow a play-bill, thus proclaiming that he has not had the heart to buy one, is to us inconceivable. We grant that it may be done, once or so, out of thoughtlessness, particularly if the borrower has given away his pence for nothing; but after the pre sent notice, we expect that nobody will think of making this excuse. It is better to purchase a bill, than to give money, even to the sellers ; for you thus encourage the sale, give and receive a pleasure, and save the venders from the temptation of begging.

A Tatler, we allow, costs two-pence, whereas the common play-bill is a penny. But if the latter be worth what it costs, will it be too great a stretch of modesty to suppose that our new play-bill is worth it also? Our criticisms, we will be sworn, have, at all events, a relish in them: they are larger; and then there is the rest of the matter, in the other pages, to vary the chat between the acts. There will even be found, we presume, in the whole paper, something not unworthy of the humanities taught on the stage. Now as to the bills that are sold at the doors, we have a respect for the common "house-bill," as it is called, that is to say, the old unaffected piece of paper, that contains nothing but the usual announcements,—the play-bill of old, or “bill o’ the play,” which has so often rung its pleasing changes in our ears, with the “porter, or cyder, or ginger-beer.”—[Formerly the cry used only to be “ porter or cyder:’’ previously to that it was “oranges :” and lately we have heard “apples.” There is a fellow in the gallery at the English Opera, who half bawls and half screams a regular quick strain, all in one note, as if it were a single word, of “bottled-porter-apples-ginger-beer.” It is as if a parrot were shouting it.]

This old play-bill is a reverend and sensible bit of paper, pretends to no more than it possesses, and adds to this solid merit an agreeable flimsiness in its tissue. But there are two rogues, anticipators of us respectable interlopers, of whom we must say a word, particularly one who has the face to call himself the Theatrical Examiner. This gentleman, not having the fear of our reputation before his eyes, sets out, in his motto, with claiming the privilege of a free speaker. "Let me," says he, quoting Shakspeare, "be privileged by my place and message, to be a speaker free." Accordingly his freedom of speech consists in praising everybody as hard as he can, and filling up one of his four pages with puffs of the exhibitions. The rogue is furthermore of a squalid appearance,— "shabby” with out being “genteel ;” and so is his friend the Theatrical Observer. The following is a taste of his quality. The analysis which is given of Mr Power’s style of humour will convey a striking sense of it to the reader: and the praises of the singers are very particular. “Power’s Paddy O' Rafferty,” says he, “was a performance exceedingly rich, and abounded with those exquisite displays of humour which has always characterised his representation of the part. The piece was throughout well cast, and very well supported. Melrose, as Captain Coradino, introduced a song composed by Lee, "Can I my love resign," which he sung with great sweetness and effect, and was loudly applauded. Mrs Chapman, as Margaritta, introduced sweetly, "On the wings of morning," from Hoffer, which she sung very effectively. Mrs Weston, of Covent Garden, made her first appearance as the Countess, and gave excellent effect to the character.” How judiciously, in this criticism, are our reflections roused by the emphatic word those, and how happily are they realized! How full of effect also are the remaining six lines! We hope these remarks will not be reckoned invidious. If the hawkers are the critics, we are sorry; but then they should put their names, and the matter would become proper.

We must not forget one thing respecting the “ house-bill,” which is, that agreeably to its domestic character, it rises in value by being within doors; costing but a penny outside the house, and two-pence in; so that no attention ought to be paid to those insidious decencies of fruit-women, who serious and elderly, dressed in clean linen, and renouncing the evil reputations of their predecessors, charge high for the honour they do you in being virtuous, and will fetch you a glass of water for a shilling. The two-pence of these peoples’ play-bills ought to retire before the sincere and jovial superabundance of the Tatler, the more virtuous because it does not pretend to be so.

We must add, that in our play-bill the names of the author will, we hope, be inserted. The printer also has suggested another refinement, which in this Anglo-Gallic age we hope will be duly appreciated; to wit, the precedence now for the first time given to the ladies.

Sources

Leigh Hunt, The Tatler. a Daily Journal of Literature and the Stage, Vol 1 Iss 12 (1830-09-17). Full text from archive.org.