Abstract

In the history of sociability, Charles Macklin, born Cathal MacLochlainn (1699?–1797) exemplifies the Irish Enlightenment and successful access to British social circles, London theatres, Anglo-Irish debating and charitable societies. Moreover, he was eager to acquire a lasting though sometimes controversial public role with, inter alia, the creation of the debating institution ‘The British Inquisition’ in 1753. He was a renowned Shakespearian Irish actor enhanced on the British stage as well as an acknowledged playwright. His pioneering and acclaimed performance in The Merchant of Venice as Shylock at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, hastened his entry and participation in the sociable British Enlightenment.

Keywords

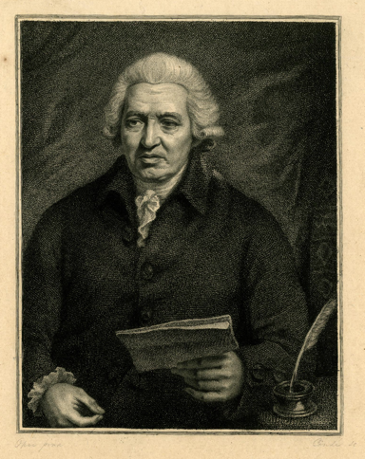

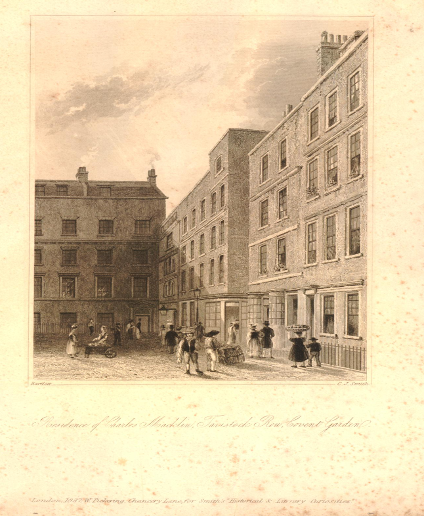

Charles Macklin was born Cathal MacLochlainn either in 1690 or 1699 (his exact birth year is uncertain) and came from the Inishowen Peninsula of Donegal Gaeltacht.1 He passed away in July 1797 at his home in Tavistock Row, Covent Garden, London.

- 1. 'Gaeltacht' is the area of Ireland where many people spoke Irish (Irish Gaelic) as a first language.

London Social Circles and Theatres

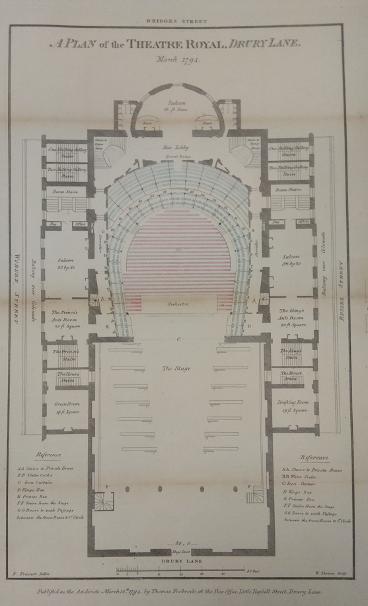

Macklin was born in a poor rural Irish-speaking and Catholic community on the far northwestern coast of Ireland and became one of the most celebrated actors of the eighteenth-century London stage. Through his quest for knowledge, he is a striking example of the influence of the Irish Enlightenment on London social circles and Anglo-Irish societies, theatres and clubs in England and Ireland. His success on the British stage (Bristol, Bath and London) and later in life on the Irish stage (in Dublin Crow Street, Capel Street and Smock Alley theatres), and the bettering of his intellect not only gave flesh and blood to the characters he played but also brought to life the ones he portrayed in his plays. Charles Macklin was the embodiment of the secret and widespread human desire among actors to metamorphose oneself, to utterly change one’s ego, name, language, faith, physical appearance, social circles and loyalties. His attempt at transmogrification is rooted in his distinguished and yet sometimes contentious and boisterous career as an actor and a playwright that lasted throughout the entire eighteenth century. He journeyed from Donegal to Dublin and London and moved from the stage to the page with a wanderlust for knowledge and sociability. He learned English (he had a library of more than three thousand books) and struggled to lose his Irish brogue2 to speak with a flawless English accent on London stages (Lincoln’s Inn Field, Drury Lane, Haymarket or Covent Garden Theatres). He was also involved throughout his life in recurring disputes and lawsuits using his gift of the gab and his extensive legal knowledge to win his trials, henceforth highlighting the undeniable relationship between the eighteenth-century courtroom and the theatre.

- 2. See on Macklin’s struggle to lose his Irish brogue: James Thomas Kirkman, Memoirs of the Life of Charles Macklin, 2 vols. (London: Printed for Lackington, Allen and Co., 1799).

Sociability and the Green Room Murder of Drury Lane

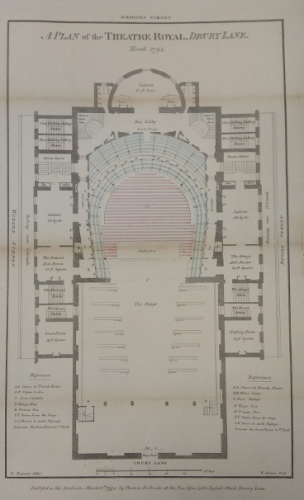

Macklin started his acting career playing minor parts in Drury Lane Theatre from 1733 onwards and became more and more involved in the theatrical productions but, on 10 May 1735, Macklin nearly lost everything he had worked so hard to obtain. He killed the actor Thomas Hallam in the green room of Drury Lane.

A quarrel aroused between the two actors and Macklin lost his temper, accusing his fellow actor of stealing his wig, an essential prop for the part he was playing. He struck his stick in Thomas Hallam’s eye untowardly piercing his brain. The injury had a fatal outcome. Hallam passed away the following day and Macklin was indicted for murder. During his trial at the Old Bailey on 12 December 1735, he oversaw his own legal defense and avoided a verdict of murder being sentenced for manslaughter. The jury sentenced Macklin to be branded on the hand and discharged him. He would henceforth study law and develop a taste for litigation. The printed auction catalogue of Macklin’s library sold in 1797 has around sixty-nine books related to Law.3 He came back to Drury Lane in January 1736 where he was surrounded by fellow actors and friends in the sadly notorious Green Room of Drury Lane. He succeeded in weaving a web of social bonds on stage and off stage. He developed the capability for sustaining interest and passion in the theatre among his fellow actors and on the political stage thanks to his extensive reading and eloquence.

- 3. The printed auction catalogue of Macklin’s library is digitized and searchable online: https://www.librarything.fr/catalog/CharlesMacklin&tag=Law.

Macklin as Shylock: Acting and Socializing

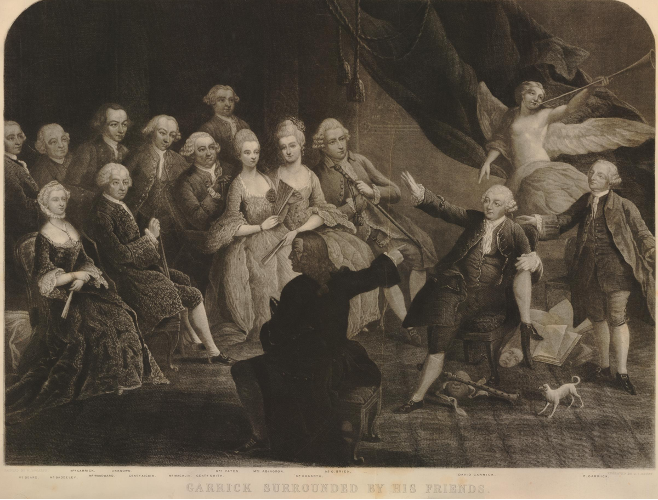

Before he was thirty years of age, his reputation as an outstanding actor grew and he became a great socializer among his fellow actors, as well as among the leading eighteenth century British literary figures and royalty. He was a close friend of David Garrick, Edmund Burke and Henry Fielding, was celebrated by Alexander Pope and even admired by royalty, in particular King George II (1683-1760). In his forties he converted to Protestantism and success was abundant. On 14 February 1741, he achieved considerable and astounding fame with his part as Shylock. Macklin prepared his acting style thoroughly and developed his eloquence, extracting from his extensive reading an intellectual and political subtext. William Appleton claims that he read Josephus’s History of the Jews4 and that his triumph was based on his repeated and careful reading of that book. His successful act of performance hastened his entry and participation in the sociable British Enlightenment. After his exceptional performance in The Merchant of Venice as Shylock, Macklin was invited by Lord Bolingbroke to dine with him at Battersea. According to Cooke, Macklin:

- 4. William W. Appleton, Charles Macklin: An Actor’s Life (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1960).

[…] attended the rendezvous and there found Pope, and a select party, who complimented him very highly on the part of Shylock, and questioned him about many little particulars relative to his getting up the play […]. Pope particularly asked him, why he wore a red hat? And he answered, because he had read that Jews in Italy, particularly in Venice, wore hats of that colour. ‘And pray, Mr Macklin’, said Pope, ‘do players in general take such pains?’ – ‘I do not know, Sir, that they do; but as I had staked my reputation on the character, I was determined to spare no trouble in getting at the best information.’ Pope nodded, and said, ‘it is very laudable’.5

- 5. William Cooke, Memoirs of Charles Macklin, Comedian: With the Dramatic Characters, Manners, Anecdotes of the Age in Which He Lived (London: J. Asperne, 1803), p. 94-95.

Macklin’s successful transformation of Shylock from the pedestrian commedia dell’arte figure of low comedy to a tragic anti-hero and villain gave him access to social circles previously inaccessible to a former Irish servant at Trinity College Dublin where, according to Kirkman, his desire for self-improvement started (Kirkman 44-45) and who had previously escaped poverty in Donegal to move from Dublin to London. He created such a mesmeric, realistic and convincing character that it is said that Pope exclaimed: ‘This is the Jew that Shakespeare drew’.

Shylock became his most successful role which he would perform for fifty years. It is even said6 that his Shylock gave a sleepless night to King George II. For David O’Shaughnessy, even Robert Walpole, the Prime Minister, came to see Macklin the following day and wondered out loud if there was a way to frighten the Commons into compliance. King George II is said to have answered ‘what do you think of sending them to the theatre to see that Irishman play Shylock?’7 From 1741 onwards, Macklin was an eager proponent of the staging of numerous plays by Shakespeare (As You Like It, Twelfth Night and The Merchant of Venice in 1741 and in 1747, The Tempest and Love’s Labour’s Lost)8 in Drury Lane. It led to the development and improvement of his pioneering and innovative acting. In a striking realistic way, he played Touchtone, Duke Frederick’s jester, the court fool in As You Like It and Malvolio, Steward to Lady Olivia in Twelfth Night in 1741. He is also said to have influenced David Garrick’s acting of Richard III in October 1741.

Macklin and Garrick

Macklin’s friendship with Garrick turned to bitter enmity. In 1773, Garrick and Macklin led a riot of Drury Lane’s actors against the manager Charles Fleetwood, who had not been able to pay them their due. This attempt at asserting actors’ rights was disastrous for Macklin. All the actors were taken on again by Fleetwood except Macklin who blamed Garrick for his exclusion. Macklin returned to Drury Lane thirteen days after the riot. But this event worsened Macklin’s public image in social circles and in newspaper reports. His public image was tainted by the past he had fought to erase, his Irishness associated in England with poverty, criminal violence (the murder of Thomas Hallam) and a tendency to squabbles whereas Garrick, using more diplomatic skills, came closer to noblemen’s circles.

- 6. David O’Shaughnessy, '"Bit, by Some Mad Whig": Charles Macklin and the Theater of Irish Enlightenment', Huntington Library Quarterly, (vol. 80, n° 4, 2017), p. 559–584.

- 7. O’Shaughnessy, David, Ireland, Enlightenment and the English Stage, 1740-1820 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- 8. Denis Donoghue, 'Macklin’s Shylock and Macbeth,' Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, (vol. 43, n° 172, 1954), p. 421–430.

‘The British Inquisition’ Debating Society

Hence, claiming a public role not usually allowed to actors, Macklin opened ‘The British Inquisition’ in 1753, which he depicted as ‘a Magnificent Coffee-Room and a School of Oratory […] the great desideratum of our Country’ (Appleton 98), a tavern-cum-lecture hall which was for Kristina Straub ‘important to the development of British debating societies and a critical link between theatre and other spaces for public opinion’.9 This institution was however notoriously unsuccessful in London social circles because of Macklin’s lowborn roots associated to his ambition to become a public figure of philosophical authority. ‘The British Inquisition’ was ‘upon the plan of the ancient Greek, Roman, and modern French and Italian societies, of liberal investigation. Such subjects in Arts, Sciences, Literature, Criticism, Philosophy, History, Politics, and Morality, as shall be found useful and entertaining to society,’ were there to ‘be lectured upon, and freely debated’ (Straub 401).10 In the Tavern, after a dinner, Macklin would give a lecture on one of the aforesaid subjects and questions, and debates with the audience would follow. ‘The British Inquisition’ failed in 1757 and Macklin’s ideal of an egalitarian debating society welcoming women and people from all walks of life, with even 800 people attending his dinner the first night in 1753, was fiercely criticized in the press. Macklin was the recipient of scathing remarks on his lowborn and Irish roots.

In 1759, he returned to the theatre and had his first success as a playwright with Love à la mode. But this play was stolen by unprincipled publishers in London and proprietors of the Crow Street Theatre in Dublin. Macklin successfully defended his ownership in the Chancery Courts and fought his whole life to assert the copyright to his plays. For Straub, Macklin ‘had a reputation for claiming his right in public venues off the stage: the court, the lecture hall and most contentiously, the newspapers’ (Straub 402).

Macklin and Legal Circles, from the Stage to the Courtroom

Macklin was on stage and off stage, transforming the stage into a courtroom and the courtroom into a stage. The most striking example is the Macbeth episode in Covent Garden Theatre. On 23 October 1773, Macklin played the role of Macbeth at Covent Garden Theatre.

After derogatory reviews of his acting as ‘Macbeth’ in the newspapers, Macklin staged a dramatic defense, addressing the audience directly on the stage before the performance of the play, with newspapers in his hand. It led to rioting in the building and Macklin was fired from the theatre. Macklin filed a lawsuit against the rioters and won his case. He refused most of the damages he was entitled to (accepting only the amount he spent for his legal fees) and the Judge, Lord Mansfield henceforth stated that ‘Mr Macklin, though an excellent player, had never acted his part so well as on that day’ (Straub 415). Later in life he was more successful in the courtroom than on the theatrical stage. As a public figure, apart from the stage, the courtroom and the press, Macklin was also part of Irish networks and societies in London. He was a member of the benevolent Society of Saint Patrick, a charity which was as well according to David Shaughnessy, ‘an important networking forum in London for Irish commercial, political and cultural elites’ (O’Shaughnessy 559-584). Macklin also belonged to the debating Robin Hood Society where he met Edmund Burke and was associated with political and legal circles like the Grecian Coffeehouse, a meeting place for generations of law students.

- 9. Kristina Straub, 'The Newspaper "Trial" of Charles Macklin’s Macbeth and the Theatre as Juridical Public Sphere', Eighteenth-Century Fiction, (vol. 27, n° 3-4, Spring-Simmer), University of Toronto Press, 2015, p. 395-418.

- 10. Straub quoting Mackliniana, an extra-illustrated edition of Francis Aspry Congreve’s Authentic Memoirs of the Late Mr. Charles Macklin, Comedian, located in the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Macklin’s Authorship and Lasting Success

Throughout the 1760’s Macklin played in Dublin where he was successful with his play The True Born Irishman (1761) at Crow Street. The play did not travel well however. In London, retitled The Irish Fine Lady, it failed utterly six years later, on 28 November 1767 after only one performance. Macklin even apologized to the audience, swearing on stage that this play would never offend their ears again. In 1990, Brian Friel adapted and renamed the play, The London Vertigo compressing Macklin’s three acts into one and reducing the number of characters from fourteen to five. Friel stated that the missing nine characters were used by Macklin ‘as contemporary stereotypes who make leisurely and amusing social comment on mid-eighteenth century Ireland’.11 The True Born Irishman was for Friel a considerable piece of work from an almost self-made man and gave him ‘a kind of comhar or cooperation or companionship with a neighbouring playwright’ (Friel 12). In the 1760s, Macklin returned to Dublin playing at Crow Street, Capel Street, and Smock Alley. His next major play in London, The Man of the World (1781) was refused a public performance license by the Lord Chamberlain’s examiner of plays. He rewrote it, lessening the anti-Scots criticism and the play was finally allowed on the British stage. Macklin’s final appearance on stage took place on 7 May 1789 with his signature role of Shylock. Unable to proceed in the part, floundering his lines, he left the stage forever and spent the last years of his life in poor health and poverty-stricken.

Macklin’s astonishing and lasting success across the London Georgian theatres and in Dublin theatres, as well as his involvement in British social circles and debating societies while overcoming social and ethnic prejudices, show how eighteenth-century sociability and a desire for self-improvement could bring fame and fortune to a Donegal Gaeltacht-born Irishman.

- 11. Brian Friel, The London Vertigo (New York: The Gallery Press, 1990), p. 11.

Share

Further Reading

Murray, Christopher, '"Encore ‘What Ish My Nation?": Irish Theatre and Drama in the Eighteenth Century Irish Theatre', Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an Dá Chultúr (vol. 27, 2012), p. 185–191.

Newman, Ian, and David O’Shaughnessy, eds., Charles Macklin and the Theatres of London (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2022).

Ritchie, Leslie, 'The Spouters’ Revenge: Apprentice Actors and the Imitation of London’s Theatrical Celebrities', The Eighteenth Century (vol. 53, n° 1, 2012), p. 41–71.

Thale, Mary, ‘The Case of the British Inquisition: Money and Women in Mid-Eighteenth-Century London Debating Societies’, Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies (vol. 31, n° 1, 1999), p. 31–48.