Abstract

A circle of amateur antiquarians established the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1780 to lay the foundation of a museum displaying Scottish and world cultural heritage. It would rapidly establish a wide network of Fellows, almost exclusively masculine, Honorary Fellows, and donors across Scotland, Britain, and Europe. The society played a central role in Edinburgh’s learned sociability and contributed to the influence of the ‘Athens of the North’ in the late eighteenth century and beyond. Unlike similar European institutions, it was not state-funded and promoted the cultural identity of Scotland within the larger political entity of Great Britain.

Eighteenth-century historical societies were the first institutions that collected traces of the past. Their museums provided long-term preservation that could not be granted to private collections and cabinets of curiosity depending on the collector’s heirs. A specific form of sociability developed among knowledgeable men who strove collectively to identify, store, sort, and protect artefacts and archives of all kinds.

The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland was a major contribution to Edinburgh’s learned sociability in the eighteenth century. It paved the way for the National Museum of Antiquities which merged with the Royal Scottish Museum into National Museums Scotland (1985).1

- 1. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland website: https://www.socantscot.org/

The founding of the society by Lord Buchan and his circle

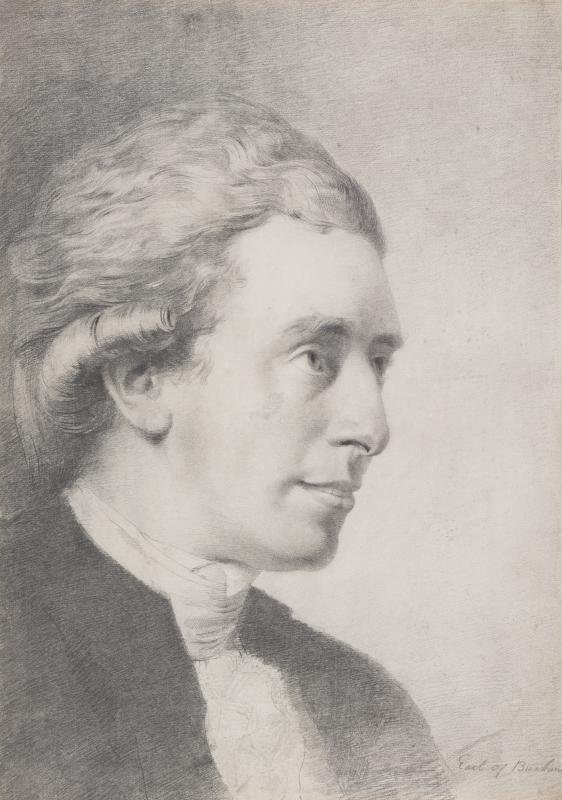

The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (SAS) - created in 1780 - was inspired by the Society of Antiquaries in London, launched in 1707 and chartered in 1753. The founder, David Stewart Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan, gathered a circle of Edinburgh acquaintances who shared his interest in the ancient history of Scotland.

When they first appeared in the 16th century, antiquaries were understood as a branch of history closely related to topography and cartography. The great antiquarians of Scotland, John Scot of Scotstarvit (1585-1670), Robert Sibbald (1641-1722), and John Clerk of Penicuik (1676-1755), produced atlases. In the eighteenth century, societies of antiquaries institutionalized the field while broadening the scope of their research to all aspects of history.2

- 2. A. S. Bell (eds.), The Scottish Antiquarian Tradition, Essays to Mark the Bicentenary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and its Museum, 1780-1980 (Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd, 1981), p. 10-11.

Lord Buchan had some expertise in the subject. In the course of his lifetime, he was involved in a number of other institutions promoting science and knowledge such as the Society of Antiquaries and the Royal Society (London), the Philosophical Society (Edinburgh), the Perth Literary and Antiquarian Society, the Royal Danish Society and its counterpart in Iceland, the American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia), and the Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston).

Buchan first introduced his project of a Scottish society of antiquarians to a party of fourteen guests he entertained in his house in November 1780. Shortly after, the society was officially created by a group of aristocrats, literati, printers, politicians, and other professionals. As the first volume edited by the society reports, some founding members ‘had made private collections, and were anxious that these, and others which they knew were scattered through the kingdom, should be preserved in a secure and permanent repository’.3

- 3. William Smellie, ‘An Historical Account of the Society of the Antiquaries of Scotland’, in Archaeologia Scotica: or Transactions of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol. I (Edinburgh: printed for the Society, 1792), p. iv.

The most active members – besides Buchan who served as vice-president – were Lord Montboddo, a jurist and philosopher, and William Smellie, a naturalist and the first editor of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Former Prime Minister Lord Bute was chosen as president to enhance the prestige of the society although he did not attend any of the meetings. The society met with success in its first years of existence and established a large network of learned men. Ten years after the first meeting in Buchan’s house, the society consisted of 32 officers, 107 ordinary members living in the Edinburgh area, 182 corresponding members and 71 honorary members from Great Britain and beyond, and a group of 23 ‘artists associated’ comprising painters, engravers, architects as well as printers. The total number of people connected to the Society of antiquaries amounted to 411 men and one woman, the Scottish portrait painter Anne Forbes.4

- 4. ‘Chronological List of the Members admitted into the Society of the Antiquaries of Scotland’, in Archaeologia Scotica, or Transactions of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol. I (Edinburgh: printed for the Society, 1792), p. xxi-xxxiii.

The society’s contribution to Edinburgh intellectual life

The society was an additional institution to Edinburgh thriving associational life and sociability of learned residents. The numerous clubs, taverns and societies played a key role in the intellectual environment of Edinburgh - one of the centres of the European Enlightenment - connecting intellectual, scientific, religious, merchant and political elites.5

- 5. Murray Pittock, Enlightenment in a Smart City: Edinburgh's Civic Development, 1660-1750 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019), p. 196-212. Mark C. Wallace & Jane Rendall (eds.), Association and Enlightenment: Scottish Clubs and Societies, 1700-1830 (Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press, 2021), p. 1-22. Stéphane Van Damme, ‘La grandeur d'Edimbourg. Savoirs et mobilisation identitaire au XVIIIe siècle’, Revue d’histoire moderne & contemporaine (vol. 55, n° 2, 2008), p. 160-166.

As a result of an influx of donations, the museum grew quickly into a collection of miscellaneous items: books and other printed material, manuscripts – including a letter signed by Mary Queen of Scots – maps, prints and drawings, and objects of all kinds and from all periods since prehistoric times, notably coins and medals. As the society had also an interest in natural history, the collection included minerals, plants, and animals such as jaws of a whale, stag heads, and exotic birds. The library was given books on a wide range of topics and the papers presented dealt with various subjects mostly related to history. For example, in 1782, W. C. Little of Liberton delivered a talk based on the museum collection entitled ‘on the warlike and domestic instruments used by the Scots before the discovery of metal’ while William Smellie gave lectures on natural history. (Bell 9-11, 31-39)

Due to its broad interest covering many fields, the society’s activities overlapped that of other Edinburgh institutions. The Faculty of Advocates opposed the Society’s petition for a royal charter on the grounds that Scottish manuscripts and printed material had been deposited in their much older library for over a century. Likewise, Edinburgh University resented Smellie’s appointment as Keeper of the natural history collections and claimed he was not entitled to give lectures since he had been rejected when applying for the chair of natural history in 1775. The Philosophical Society also disapproved of the Society of Antiquaries enlarging its scope to science. Instead of having two competing associations, it was suggested they merged into a single ‘Royal Society’ encompassing all scholarly research. However, the King granted the Society of Antiquaries a charter on 6 May 1783 while the members of the Philosophical Society – predominantly focused on science – were incorporated as the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Some, like Smellie, remained members of both. (Bell 15-17, 41)

The building of a Scottish cultural identity

The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland nourished intertwining scientific and political ambitions. The collecting of old maps, public as well as private archives, artefacts and remains would contribute to a better understanding of the history of the peoples who once lived in Scotland. By the same token, writing the history of the nation, highlighting what Buchan called its ‘attainments’, and paying tribute to its heroes and great writers was expected to strengthen devotion to the native country among the public.6

- 6. ‘Robert Anderson to John Eliot, February 8, 1805’, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical society, vol. 1, p. 174.

The commitment to nation building was not specific to the Edinburgh Society of Antiquaries, yet it struck a chord in Scotland since the nation had relinquished its sovereignty for the sake of an incorporating union with England and Wales in 1707. William Smellie emphasized that it was possible ‘to call the attention of the Scots to the ancient honours and constitution of their independent monarchy’ since the union with England had been strengthened thanks to ‘a warm and mutual attachment to the same family and constitution’. (Smellie 2) The agenda was to show that the Scots had done as well as the English, as far as literature and science were concerned. This incentive to national pride was not meant to hinder the rise of a British identity, but to assess a Scottish cultural identity within the Union. As Colin Kidd pointed out, the stress put on Scottish singularity did not lead to a nationalist surge in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.7

- 7. Colin Kidd, Subverting Scotland's Past: Scottish Whig Historians and the Creation of an Anglo-British Identity, 1689-c. 1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

This approach constituted a major shift as compared to the older generation of Enlightenment thinkers – notably historian and Church leader William Robertson – who did not value the remote past of their nation. Buchan and his colleagues intended to unearth Scottish writers and historians from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries through a series of biographies of outstanding Scots (Biographica Scotica). The Earl collaborated with mathematician Walter Minto to produce An Account of the Life, Writings, and Inventions of John Napier, of Merchiston, the inventor of logarithms. However, Minto emigrated to the United States and the other volumes of the collection never came out. Buchan cherished another project, a collection of portraits of famous Scots (Iconographia Scotica) which did not come into existence either.

Contemporary Scotland was as much an object of interest to the Scottish antiquarians, ‘The principal object of the Society’ being ‘the ancient, compared with the modern state of the kingdom’. (Smellie xvi) Under the leadership of Lord Buchan, the society launched a plan to draw up an inventory of the parishes of Scotland. An announcement appeared in the press in 1781 but the results of this ‘general parochial survey’ – which remained incomplete – were published only ten years later. A much more comprehensive survey, The Statistical Account of Scotland, was completed by Sir John Sinclair in 1799 without the assistance of the SAS.

Scottish, British, European, and transatlantic networks

The first formal meeting took place in the Hall of the Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge. In the first years, the ordinary members met on a regular basis in the house of the society located in the Old Town of Edinburgh which also hosted the museum, a reading room, and the lodging of the secretary, James Cummyng. The house was sold due to lack of funding in 1787 and the collection was subsequently moved several times to renting apartments, until a house was bought in Castle Hill in 1794. On a unique occasion, the society met in a tavern, the Douglas in Anchor Close in 1795. (Bell 13, 34-35, 48, 53-55) The Edinburgh circle of antiquarians discussed the running of the society and its financial issues – as funding came solely from subscriptions fees that were often overdue –, elected new members and admitted or rejected papers previously expertized by the four censors for the publication of the Transactions of the Society. They would hear Lord Buchan’s annual address and papers based on the museum’s collections.

The ordinary members interacted with other members living in Britain and abroad through correspondence, exchange of books or papers for the Transactions, and donations. The Edinburgh circle created a network of donors who provided the museum with items coming both from Scotland and other parts of the world. Like other societies of antiquaries, the SAS wished to collect archives related to Scotland but also to set the nation artefacts in broader context. The network can be mapped thanks to the 1792 list of members. Non-ordinary members – a social mix of aristocrats and professionals – were located in Scottish university centres (Saint Andrews, Glasgow, Aberdeen), London and other English towns as well as Ireland. Reverend Edward Ledwich, an Irish antiquarian, sent ten flat bronze axe heads in 1784 which marked the beginning of a strong relationship between the SAS and Ireland.

A more limited second circle was composed of members living in France, Spain, Poland, Italian cities, Russia, and Scandinavia. Some were purely honorary members, like Buffon and Diderot, others were holding a position that made them useful to the society, like Abbe Gaetano Marini, ‘Praefeft of the Secret Archieves of the Vatican’. A number of associates in the Scottish diaspora were called upon to search for manuscripts related to the history of Scots living abroad, particularly in the archives of the Vatican, the Scots College in the University of Paris, and the convent of Würtsburgh in the Bavarian region. (Van Damme 171) In the eighteenth century, the network just started to span across the Atlantic with the election of Benjamin Smith Barton, an American naturalist at Philadelphia University.

Scandinavians were important partners, due to the historical connection with Scotland and the early start of associations of antiquarians in Denmark (1745), Sweden (1753), Norway (1760), and Iceland (1791). Buchan befriended Grímur Jonsson Thorkelin, Assistant Keeper of the Royal Archives in Copenhagen, who was elected to the SAS in 1783 and was instrumental in the Earl’s election to the Royal Danish Society two years later. In 1787, Sir Alexander Seton of Preston and Ekolsund offered an eleventh-century runestone from Lilla Ramsjö, Sweden, which is currently on display outside 50 George Square, next to the University of Edinburgh’s School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures (Smellie xxi-xxxii). The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland was undoubtedly a center of sociability of learned men in Scotland, Britain, and Europe who communicated directly or remotely to exchange ideas, information, and objects.

Despite its success in gathering a large network and in building a collection for its museum, the SAS lacked financial support from the state and depended on the commitment of its leading members. It survived the founder’s resignation in 1790 and continued to thrive in the 19th century but did not centralize all collections related to Scotland like a state museum. As a private institution in a nation incorporated into a larger one, the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland stimulated a specific form of learned sociability.

Share

Further Reading

Guichard, Charlotte & Van Damme, Stéphane (eds.), Les Antiquités dépaysées. Une histoire globale des cultures antiquaires au XVIIIe siècle (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2022).

Kerr, Robert, Memoirs of the life, writings, and correspondence of William Smellie; with a new introduction by Richard B. Sher (Bristol: Thoemmes, 1996).

Marsden, Richard A., Cosmo Innes and the Defence of Scotland’s Past c. 1825–1875 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014).

McElroy, Davis Dunbar, Scotland’s Age of Improvement: A Survey of Eighteenth-Century Literary Clubs and Societies (Washington: Washington State University Press, 1969).

Ross, Anthony, ‘Three Antiquaries: General Hutton, Bishop Geddes And the Earl Of Buchan’, The Innes Review (vol. 15, n°2, December 1964), p. 122-139.

Sheridan, Alison, ‘Collecting European antiquities as part of the Scottish antiquarian tradition’ in Luc Amkreutz (ed.), Collecting ancient Europe: National Museums and the search for European Antiquities in the 19th-early 20th century (Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2020), p. 69-83.

Sweet, Rosemary, Antiquaries: the discovery of the past in eighteenth-century Britain (London; New York: Hambledon and London, 2004).

Williams, Kelsey Jackson, ‘Antiquarianism: A Reinterpretation’, Erudition and the Republic of Letters (vol. 2, n°1, 2017), p. 56-96.

![‘Seal of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland’, in Archaeologia Scotica: or Transactions of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, volume I. Printed by William and Alexander Smellie, printers to the Society, for William Creech, Edinburgh, and T. Cadell, in the Strand, London. Booksellers to the Society, Edinburgh et M, DCC, XCII. [1792], front page.](/sites/default/files/styles/notice_full/public/2024-02/SOCIETY%20OF%20ANTIQUARIES%20Transactions_of_the_Society_of_the_Antiquaries_of_Scotland._Illustrated_with_copperplates._Volume_I._Fleuron_T145138-1.png?itok=pd_GMNYg)