Résumé

As British ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples between 1764 and 1800, Sir William welcomed guests from across Europe. He showed them his vast collections of antiquities, accompanied them to excavation sites, and shared with them his passion for vulcanology. Different forms of entertainment were also organized for them. His first wife Catherine organized concerts, and his second wife Emma performed her Attitudes and danced the tarantella in front of assembled guests. In another set of performances, young boys splashed naked in the waters in front of his villa.

Mots-clés

As British ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples, Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803) welcomed guests from across Europe.1 Described in the seventeenth century as a paradise inhabited by devils,2 Naples had, by the late eighteenth century, become a requisite stop as a Grand Tour destination, due, in large part, to the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum and to Vesuvius being in an active phase. During the 35 years he spent in Naples, Sir William welcomed aristocrats, diplomats, Grand Tourists, artists, exiles from the French Revolution, and all those interested in the archaeological explorations that were feeding the development of neoclassicism and/or who were interested in witnessing the volcanic activity. Sir William’s home thus became a hub of sociability, where people coming from far and wide could meet, exchange opinions about what they were experiencing, and network. There was something haphazard about these meetings, in that one could never be certain who they might encounter, but these were always ‘quality’ individuals and this very haphazardness had its own benefits, in that it assembled people who would not otherwise have had the opportunity to be together in the same space.

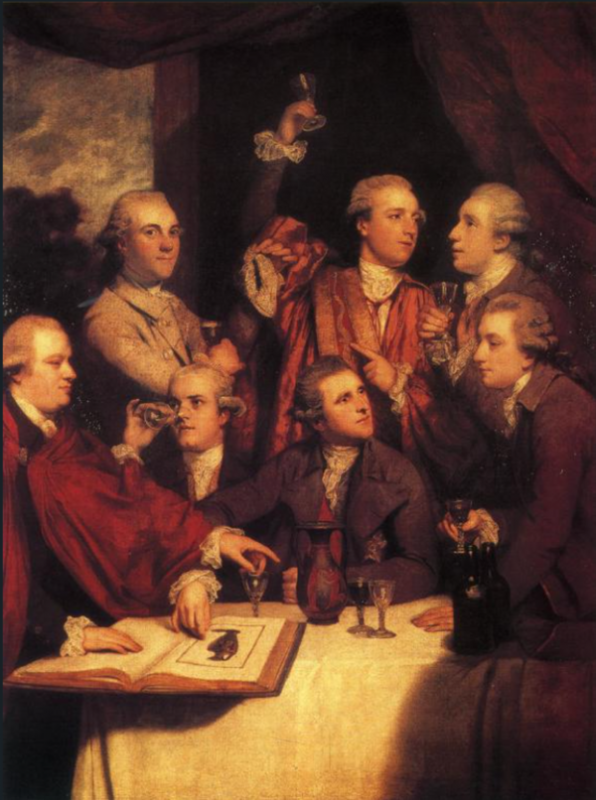

Sir William was the perfect host and shared his various passions with his guests. He accompanied them to excavations sites and showed them his vast collections of virtú – all occasions for sociable exchange. He was known for his considerable collections of antique vases and commissioned the ‘baron’ d’Hancarville to coordinate a four-volume publication of his first collection.3 This is featured in the group portrait that was painted by Joshua Reynolds, which shows Sir William’s induction into the Society of the Dilettanti (see above). Six men sit or stand around Sir William, discussing the vase on the table and its reproduction in the volume open at that page, while they drink and recall, perhaps, their various Grand Tour exploits. These publications, as this painting shows, provided further opportunities for sociability.

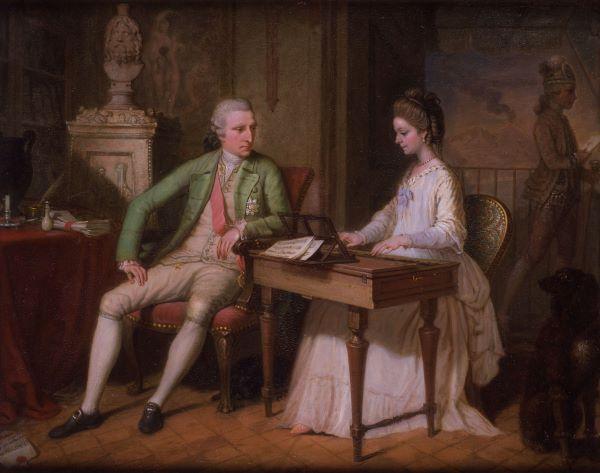

Sir William also shared his passion for vulcanology with his visitors. Three relatively important eruptions occurred while Sir William was in Naples, in 1767, 1779, and 1794. Nicknamed the ‘Modern Pliny of Vesuvius’,4 Sir William explored the volcano, then sent letters back to the Royal Society in England detailing his observations of Vesuvius, where they were read aloud, together with drawings and rock samples. In letters and memoirs, visitors recalled their own reactions and those of the people who accompanied them in Sir William’s volcanic tours. When Sir William arrived to take up his post in Naples in 1764, he was accompanied by his first wife, Lady Catherine (1738-1782). She was an accomplished musician, particularly of the harpsichord, which she is shown playing in a portrait of the couple painted in 1770.

- 1. Sir William Hamilton owned four homes in and around Naples: his main residence was the Palazzo Sessa, but he also owned the Villa Angelica, the Casino at Posillipo (later named Villa Emma), and a home in Caserta, near King Ferdinand and Queen Maria Carolina’s palace. For more on Sir William and Emma Hamilton, see Ersy Contogouris, Emma Hamilton and Late Eighteenth-Century European Art: Agency, Performance, and Representation (London: Routledge, 2018).

- 2. ‘Un paradis habité par des diables.’ Maximilien Misson, Nouveau voyage d’Italie, 3rd ed., 1691 (The Hague: Henry van Bulderen, 1698), vol. 2, p. 53.

- 3. Sir William sold his collection of vases to the British Museum, after which he immediately started a second collection, the publication of which was illustrated by the German painter Wilhelm Tischbein.

- 4. G. de Soulavie, Œuvres complètes de M. le Chevalier Hamilton (Paris: Moutard, 1781), pp. 278 and 454.

In a letter to his wife, Leopold Mozart writes that he and his then fourteen-year old son were welcomed to the Hamiltons’ home and that Catherine had ‘trembled at having to play before Wolfgang’.5 Catherine also had her own circle of friends, with whom she organized events, for instance a concert that the young Mozart gave in May 1770 at the home of Countess von Kaunitz, the wife of the Imperial ambassador.6 Networks of sociability were therefore built by both the men and the women living in Naples long term, and visitors to the area would integrate these networks.

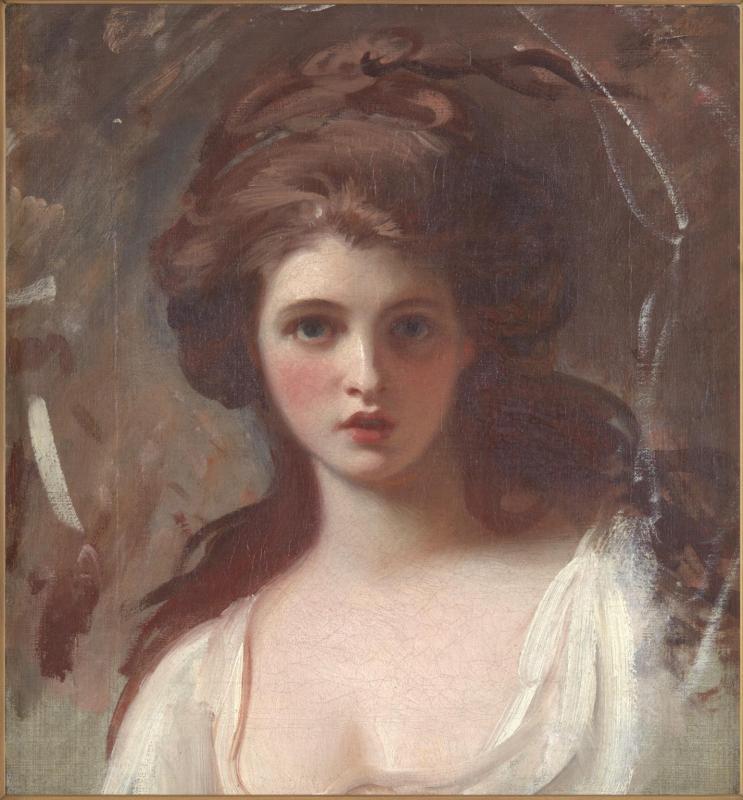

Suffering from ill health, Lady Catherine died in 1782. Sir William travelled to England to bury her and settle her estate. There, he met his nephew’s mistress, Emma Hart. Born Amy (or Emy) Lyon in or around 1765, at Ness, in the Wirral Peninsula in Cheshire, she was raised by her mother in relative poverty.7 Her father, a blacksmith at the local coal mine, died when Emma was a few weeks old. After this inauspicious beginning, Emma’s vertiginous rise into, and eventual spectacular collapse from, the highest echelons of society, prompted the French portraitist Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who would later paint Emma, to reflect: ‘La vie de Lady Hamilton est un roman’.8 When she was thirteen or fourteen years old, Emma moved to London to work in service and with the hopes of a career on the London stage, but she was forced into sex work. She is believed to have worked in a brothel and at the quack doctor James Graham’s Temple of Health before becoming the mistress of the minor aristocrat Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh in 1781 (it is around this time that she became known as Emma), and then the following year, of Charles Greville, son of the Earl of Warwick and nephew of Sir William Hamilton. When Emma went to live with Greville, she was pregnant, and her daughter was sent to be raised by Emma’s family. It is then that Emma began posing for the painter George Romney; these were often occasions for Greville’s and Romney’s friends to congregate, as was the frequent practice with sittings at the time.

- 5. Leopold Mozart letter to his wife, Naples, May 9, 1770, in The Letters of Mozart & His Family, ed. Emily Anderson, vol. 1 (London: Macmillan and Co., 1938), p. 199.

- 6. Lady Catherine organized this together with Princess Belmonte, Princess Francavilla, Duchess Calabritta, and Countess von Kaunitz. Leopold Mozart, letter to his wife, Naples, May 26, 1770, in The Letters of Mozart & His Family, p. 206.

- 7. For a fuller discussion of Emma’s life and performances, see Contogouris, Emma Hamilton.

- 8. Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun, Souvenirs 1755-1842, [1835-37], ed. Didier Masseau (Paris: Tallandier, 2009), p. 173.

After four years, Greville, who was a second son and therefore not poised to inherit much money, wished to put an end to his liaison with Emma in order to secure an advantageous marriage. He sent Emma to Naples to live with his uncle, where she became first Sir William’s mistress, and then his wife. She entertained with him, became the favourite of Queen Maria Carolina of Naples, and hosted large parties. She also provided the entertainment, dancing the tarantella or performing her Attitudes for her guests. Dressed in classic attire, the beautiful, sensual, and seductive Emma adopted poses (or attitudes) reminiscent of mythological, religious, and literary figures in classical statuary works of the great masters, and paintings found on ancient vases and on the recently excavated walls at nearby archaeological digs. Between each pose, she covered herself with shawls, then uncovered herself and presented herself as if a statue. She executed sometimes more than two hundred such posesJohn B.S. Morritt of Rokeby, The Letters of John B.S. Morritt of Rokeby: Descriptive of Journeys in Europe and Asia Minor in the Years 1794- 1796, ed. G.E. Marindin (London: John Murray, 1914), pp. 281-2. in rapid succession in front of an enthralled public, some of whom compared her performance to the ancient art of pantomime.Ismene Lada-Richards, ‘‘Mobile Statuary’: Refractions of Pantomime Dancing from Callistratus to Emma Hamilton and Andrew Ducrow’, International Journal of the Classical Tradition (vol. 10, no. 1, Summer 2003), pp. 3-37. Emma’s Attitudes and their combination of classicism and erotic poses became one of the requisite Neapolitan experiences, on the same level as the antiquities that could be seen there: the portraitist and history painter William Artaud, who visited Italy in 1796 as a Royal Academy scholar, wrote that, ‘The environs of Naples are truly Classic Ground […] I have been at Herculaneum & Pompeii & the Museum at Portici, & saw Lady Hamilton’s attitudes’.William Artaud, quoted in Ian Jenkins and Kim Sloan (eds.), Vases and Volcanoes: Sir William Hamilton and his Collection (London: British Museum Press, 1996), p. 261. Although some spectators described the performance as scandalous,Jeffrey N. Cox, Poetry and Politics in the Cockney School: Keats, Shelley, Hunt, and Their Circle (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 171. the classical dimension of the Attitudes seemed to have provided for most viewers enough of a counterpoint to render it acceptable for the wife of the English ambassador to display her body in such a way. In Sir William’s drawing room, then, people assembled to watch the Attitudes, react to them, emote, attempt to recognize (and sometimes shout out) which character she was performing, and later wrote letters back home about these performances. On other evenings, Emma danced the tarantella, a dance adapted from local Neapolitan practices.

There were other opportunities for sociability at Sir William and Emma’s home. As with Romney’s studio, these portraiture sessions in which Emma posed were often attended by others. Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun recalls a sitting with Emma at Caserta, which was attended by the Duchess of Fleury and the Princess Joseph of Monaco, which was followed by all of them having lunch together with Sir William (Vigée Le Brun 175). Sir William organized other spectacles during the daytime. Vigé Le Brun and Goethe both relate in their memoirs that Sir William hired young boys to splash in the shallow waters by his seaside Casino in Posillipo (Vigée Le Brun 177).13 There were therefore many opportunities for visitors to congregate and exchange, many opportunities for sociability, either mediated through displays such as the young fisher boys, Emma’s Attitudes or her dancing of the tarantella, through the practice of portraiture, at dinners, or with Sir William taking his guests to see his collections or to visit the volcano.

- 13. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey [1816-1817], translated by W.H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer (Harmondsworth: Penguin, [1982] 1986), p. 353. For more on these performances, see Ersy Contogouris, ‘Neoclassicism and Camp in Sir William Hamilton’s Naples’, ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640-1850 (vol. 9, no. 1, 2019).

In 1799, when Napoleon Bonaparte’s armies invaded Naples, Emma and Sir William helped the Neapolitan royal household flee to Palermo. It is there that Emma’s affair with Admiral Nelson developed. Life in Sicily for the two thousand or so refugees from Naples was full of social occasions, and Emma started to gamble heavily. In 1800, Nelson and Sir William were both recalled to London. Emma, at this point, was pregnant with Nelson’s child.14 Back in London, Emma, Nelson, and Sir William lived together in a house they bought in the suburb of Merton, near what is now Wimbledon. Seemingly unperturbed by the gossip, conjecture, and caricature brought about by their living arrangement, the ménage à trois toured England and continued to host suppers at their home until Sir William’s death in 1803. Sir William left the bulk of his inheritance to his nephew Greville. Nelson died in 1805, after which Emma, assailed by debts from overspending and gambling, fled to Calais, where she died in poverty in 1815. Her passing in near anonymity was a far cry from the scintillating sociable activity of which she had once been the centre.

- 14. The child, Horatia, was presented as being the daughter of a Mr. Thompson, a sailor under Nelson’s command, and his wife, who had entrusted her care to Nelson. Horatia eventually came to recognize that Nelson was her father, but never accepted that Emma was her mother.

Partager

Références complémentaires

Colville, Quentin (ed.), Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity (London: Thames & Hudson, 2016).

Contogouris, Ersy, Emma Hamilton and Late Eighteenth-Century European Art: Agency, Performance, and Representation (London: Routledge, 2018).

Davies, Kate, ‘Pantomime, Connoisseurship, Consumption: Emma Hamilton and the Politics of Embodiment’, CW3 Journal (vol. 2, Winter 2004).

d’Osmond, Éléonore-Adèle, Comtesse de Boigne, Récits d’une tante: mémoires de la Comtesse de Boigne, née d’Osmond (Paris: Émile-Paul Frères, 1921-1923).

Hornsby, Claire (ed.), The Impact of Italy: The Grand Tour and Beyond (London: The British School at Rome, 2000).