Abstract

Connoisseurs of art and literature from all over Britain were known to grace Madame du Deffand’s salon on rue Saint-Dominique. Her correspondence with Horace Walpole gives us a window into how Franco-British epistolary relationships helped shape new spaces of sociability, both real and imagined.

Keywords

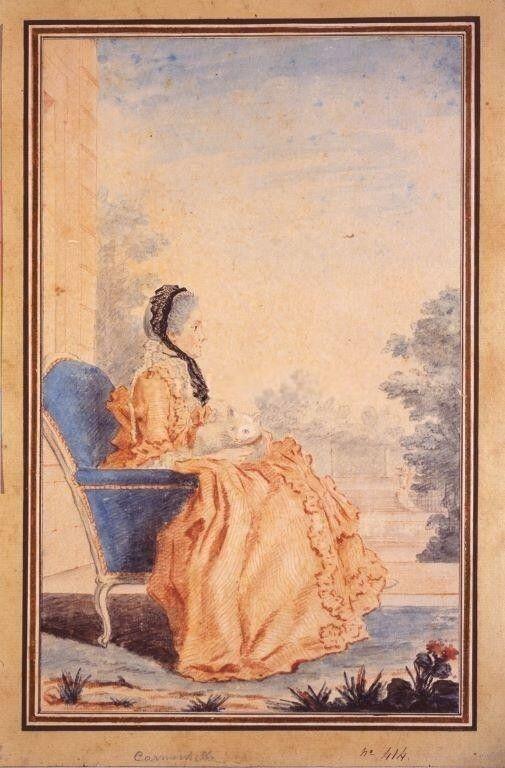

Madame du Deffand, née Marie de Vichy-Champrond, was born in 1698 into an old but impoverished provincial noble family. In 1718, following an education received at the Benedictine convent of Madeleine de Traisnel, in Paris, she married Jean-Baptiste-Jacques Du Deffand, marquis de La Lande. She would sever all ties with her husband 10 years later. For a time, she lived a life of pleasure at the court of Sceaux, where she met Voltaire, and later became close with the president of the Chambre des enquêtes, Charles-Jean-François Hénault, who shared her love of repartee and sociability. The marquise du Deffand was a spirited woman with a sharp tongue. She presided over the salon she established in 1747 from her tonneau (a great hood chair), rapidly coming to rival another famous salonnière, Madame Geoffrin,1 who would play a definitive role in financing the Encyclopédie. Benedetta Craveri describes Madame Geoffrin’s salon as ‘the expression of an enlightened bourgeoisie, eager to assert its cultural titles,’ while in contrast, Madame du Deffand’s society embodied ‘the insularity of a nobility that was exceedingly exclusive […] and intent on safeguarding its cachet and language.’2

Madame du Deffand had solidified her friendship with Voltaire as she partook in the literary and worldly games offered at the residence of Lord Bolingbroke before his recall from exile in 1723. At the age of 51, she settled into her salon in the Saint-Joseph convent on rue Saint-Dominique, where she played hostess to her circle of faithful friends: Président Hénault; Antoine de Ferriol, the comte de Pont-de-Veyle; Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Formont; Madame de Luxembourg; Madame de Mirepoix, the duchesse d’Aiguillon; the academician Jean D’Alembert; philosophers such as François-Jean de Chastellux and Michel-Etienne Turgot; painters Charles-André van Loo and Claude-Joseph Vernet; and sculptor Étienne Maurice Falconet. As she was subject to frequent episodes of insomnia and melancholia, she sought respite in the luncheons hosted by Madame de Lauzun, Madame de Vallière, and the Camarans. By 1753, Madame du Deffand was completely blind. She took on Julie de Lespinasse as her personal reader but, after a falling-out in 1764, put an end to their relationship.

Madame du Deffand’s salon quickly gained international renown. Foreign visitors to Paris flocked to participate in her celebrated evening repasts, where the art of conversation à la Française and the pleasures of refined sociability ruled. She received diplomats from all over Europe: baron Gleichen, Gustaf Philip Creutz, Johan Bernstorff (the Danish extraordinary envoy to Paris from 1744 to 1751), marquis Caraccioli (the Neapolitan ambassador from 1771 to 1781), and Count Ulrik Scheffer (the Swedish minister to Paris from 1744 to 1751).

George Selwyn introduced Horace Walpole to ‘the blind old bat’ in 1765. She was 68 at the time. In a letter Walpole wrote in 1766 to his friend, the poet Thomas Gray, he chronicles the multifaceted sociability of an active elderly woman with a busy social calendar.

Madame du Deffand […] is now very old and stone blind, but retains all her vivacity, wit, memory, judgement, passions and agreeableness. She goes to operas, plays, suppers, and Versailles; gives suppers twice a week; has everything new read to her; makes new songs and epigrams, ay, admirably, and remembers every one that has been made these fourscore years. She corresponds with Voltaire, dictates charming letters to him, contradicts him… In a dispute, into which she easily falls, she is very warm, and yet scarce ever in the wrong.3

Walpole would return to Paris on several occasions in 1767, 1769, 1771, and 1775. Over the course of those years, Madame du Deffand’s salon became a popular destination for British writers and eccentrics, men of state, and amateurs of art, literature, philosophy, and politics. John Craufurd, Gilbert Elliot, James Macdonald, Lord Robert Darcy, Lord Shelburne, Lord Bath, Charles James Fox, Charles Fitz Roy, David Hume, Edward Gibbon, and John Taaffe figured among her distinguished guests.

- 3. Walpole to Thomas Gray, 25 January 1766, cited by Jacqueline Hellegouarc’h in L’Esprit de société. Cercles et salons parisiens au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Editions Garnier, 2000), p. 174.

The letters Madame du Deffand exchanged with Walpole4 between 1766 and 1780 give us a window into how Franco-British epistolary relationships helped shape new spaces of sociability, both real and imagined. The two shared a mutual admiration for Madame de Sévigné, whose letters, circulated from hand to hand or read publicly, were an extension of salon conversation, sustained by rumours, anecdotes, fait divers, and literary and philosophical ruminations. Walpole criticised the French for their sharp tongues and feigned politeness, while Madame du Deffand defended the superior good taste of her compatriots. But it was in theatre production and the adaptation of British theatre for the French stage that differences between the two countries would become most evident. Madame du Deffand had invited the Pembrokes to attend the performance of a young actress, Mademoiselle Clairon, at the Montigny residence, but claimed she did not appreciate the maudlin play-acting currently in fashion in France and regretted that contemporary literature was ‘as sterile as it was abundant.’5 She was shocked by the liberties Shakespeare had taken with his art, though she confessed she found his departure from the three unities provided a wellspring of beauty. In a letter dated August 8, 1773, she attempted to placate her correspondent with the following nuances: ‘I am blind to Shakespeare’s merits; but as I hold your judgement in high regard, I must therefore conclude that the fault lies with the translators.’6 To keep the conversation flowing between friends, the rules of sociability sometimes called for honeyed words.

- 4. Horace Walpole’s Correspondence with Madame du Deffand and Wiart, dans Horace Walpole's Correspondence. The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole's Correspondence, ed. Wilmarth Sheldon Lewis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1939), vol. 3-8.

- 5. Horace Walpole, op. cit., vol. 4, t. II, p. 18.

- 6. Ibid., vol. 5, t. III, p. 390.

Share

Further Reading

Caron, Mélinda et Charrier-Vozel, Marianne, ‘Prolégomènes à une édition de la correspondance complète de Mme du Deffand‘, Épistolaire (n° 38, Paris: Éd. Honoré Champion, 2012), p. 193-214.

Charrier-Vozel, Marianne, ‘Sociabilité franco-britannique et création théâtrale dans les correspondances de Mme du Deffand et de Mme Riccoboni‘, dans A. Cossic-Péricarpin et H. Dachez (dirs.), La sociabilité en Grande-Bretagne au Siècle des Lumières. L’émergence d’un nouveau modèle de société, t. II, Les enjeux thérapeutiques et esthétiques de la sociabilité au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Éd. Le Manuscrit, Collection "Transversales", 2013), p. 285-310.

Péralez-Peslier, Bénédicte, ‘À ‘l’ami d’outre-mer’: Marie du Deffand ou l’accomplissement de la sociabilité par procuration dans sa correspondance franco-britannique avec Horace Walpole (1766-1780)‘, dans A. Cossic-Péricarpin et A. Kerhervé (dirs.), La Sociabilité en Grande-Bretagne au Siècle des Lumières. L’émergence d’un nouveau modèle de société, t. V, Sociabilités et esthétique de la marge (Paris: Éd. Le Manuscrit, Coll. "Transversales", 2016), p. 175-195.